I still vividly remember the first time I met Tom Meluch in person (well, for longer than 10 minutes, anyway - we had played a show together with Loscil in Philadelphia in 2016 but had no time to hang out).

It was the lower level of a Los Angeles hotel’s parking lot in October 2018, just before a west coast tour with him and Marcus Fischer. Typical pleasantries ensued as we piled gear into the rental minivan, and as the day progressed, I just couldn’t stop thinking to myself: “how is this guy for real?”

That’s because the man behind the Benoît Pioulard recording project is an impossibly kind, unfailingly gentle soul; he’s the kind of person you want to hang out with all the time.

As the tour rolled on across thousands of miles and several hotel rooms, I kept waiting for Tom to snap or break character. There were plenty of opportunities to do so: a ridiculously antagonistic promoter in Berkeley harassing him during sound check; a 4 A.M. pounding on the door from the San Francisco Fire Department for a tiny bit of smoke emanating from our fire pit out back of the Airbnb; a catastrophic technical issue at one venue that cut his set short…despite hurdle after hurdle, he never flinched. In fact, he only got nicer as the days went on: cooking breakfast for us, waxing poetic about fantastic choices on the AUX cord, making witty and self-deprecating jokes, and just generally being a fantastic human being to share a van with.

His personality is a near perfect match for the sort of comforting and enveloping “ambient folk” music he’s come to be known for. Across a remarkable catalog spanning over 20 years with labels like Kranky, Morr Music, and a litany of others as a solo artist and collaborator, you get the sense that he’s truly in this for the right reasons. There’s no pretension, and not even the slightest air of superiority, despite all of his accomplishments. What you see is what you get with Tom.

This carries over into his creative process, too. His unassuming recording techniques, centered on an old Mac running GarageBand with a few effects pedals scattered about, are a huge part of his sound, which has come to be defined by an ever-present hint of beautifully gritty cassette tape textures (tapes he records himself, mind you, without plugins or other digital tricks) and an overall “organic” sensibility, as he puts it. There’s really nothing artificial about him or his music.

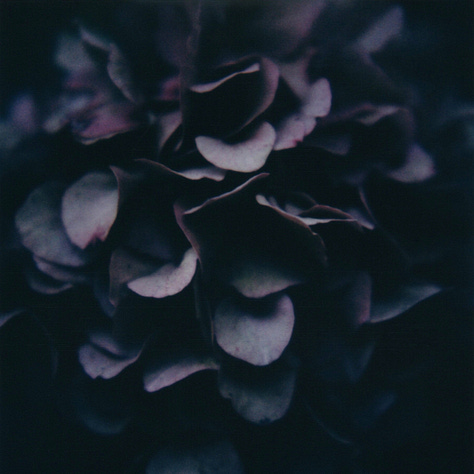

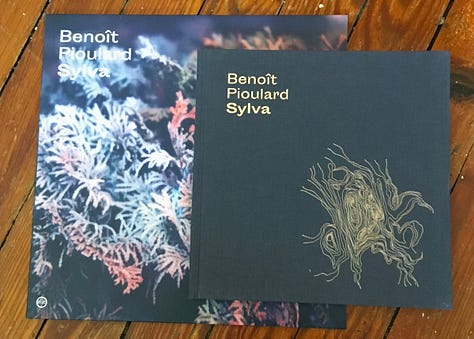

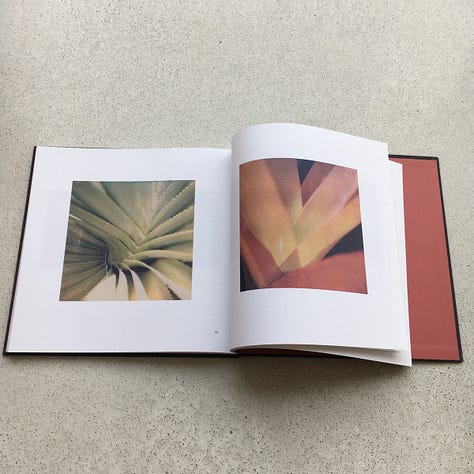

His Polaroid photography is the cherry on top of all this. As if the man couldn’t match his music any more perfectly, his trademark SX-70 images - replete with “real deal” and unedited artifacts and imperfections - only enhance the sense of authenticity and analog aesthetics at play.

It was a joy to have Tom on the 2nd edition of this podcast (check out the first here with our other tourmate from that 2018 run, Marcus Fischer) to revisit some of these memories and also dig deeper into his musical past, his photography, exciting upcoming plans, and much more. I spoke with him over videoconference from his home in Brooklyn, NY, on the morning of Friday, February 2nd.

Here’s my interview with Tom Meluch (Benoît Pioulard) - listen above, or read below.

Click here to subscribe to Tom on Bandcamp - you’ll support his work directly and receive exclusive tracks on a regular basis. Highly recommended.

Transcript

Sound Methods 002 - Benoît Pioulard

Andrew: Welcome back to Sound Methods. Today, I'm joined by Tom Meluch, also known by his pseudonym, Benoît Pioulard.

Tom is a dear friend and one of my favorite musicians in the modern ambient scene. For 20 years, he's been steadily churning out one beautiful album after another on heavy-hitting labels like Kranky, Morr Music, Beacon Sound, A Strangely Isolated Place, and many others, all of them in his distinctive gauzy, tape-drenched style.

His songs straddle the line between ambient and folk, with equal amounts of droning atmosphere and structured arrangement. His calming baritone voice adds a wistful, nostalgic element to some tracks, while bringing a tangible, human feel to an otherwise ethereal sound that's primarily captured through tape recorders and other simple, minimal means.

He's worked with a huge range of collaborators, such as Rafael Anton Irisarri (as Orcas), Jason Corder, Sean Curtis Patrick, and Lusine, among countless others. He's also shared stages on national and international tours with Loscil, A Winged Victory for the Sullen, Windy and Carl, and so many more. Tom has become well known for his exceptional eye for Polaroid photography, with many of his images gracing the covers of not only his own albums, but a host of other musicians’ in the last few years.

I talked to Tom at length about a wide range of topics, including the process and philosophy behind his music, his photography, as well as his recent cross country move from Seattle to New York. Here's our interview.

Andrew: Thanks for hopping on, Tom. Appreciate you being here.

Tom: Yeah, it’s an honor. I'm pleased you're doing this.

Andrew: We go back a long way, and in thinking about the music that you make, I think you have a very unique voice within this quote unquote, “ambient” space that we both inhabit. You straddle that line between droney ambient sound, but you also have quite a bit of folk and almost pop influence in your music. There are lyrics, and there's a clear arrangement and structure that I don't think is present in a lot of our peers’ music, at least not as obviously as some of the work that you do. And so I'm curious how you would characterize the music that you make: is it ambient? Is it something else? Do you even care what people call it, or is there like a sonic reference point that you're going for? Or is all this just like the natural output of your influences in your work?

Tom: Yeah, it's much more the latter, or like the tail end of what you were saying there. It's a confluence of things all together, because I was a pretty voracious music consumer starting from…oh, I don't know, age seven or eight. I was lucky to have parents who let me watch MTV in the early 90’s, which was obviously a very fertile time for a lot of good, weird stuff that just doesn't enter the mainstream anymore. It seems…not to be an old man about it, I mean, but in retrospect, I've come to realize that some of the stuff that I was most innately attracted to had a lot of texture going for it.

My first two favorite records, I think, were "In Utero" and Breeders "Last Splash," and those are both…those both have such, like, particular production styles, super raw for the most part, and everything is very distinct and three dimensional. And that's the kind of thing that really set my brain off from a pretty early age.

And then going forward, yeah, I generally grew up…well, being from Michigan in the 90’s, it was a lot of alternative radio and that sort of thing, and then as soon as I came upon those, it came down to my friend Ryan Jones who I met in, like, seventh grade. He transferred from another school, and I think one day was wearing a Tool t-shirt or something, so I talked to him in the lunch line, whatever, and we became very fast friends. And he had like a super weird eye and ear for film and music. And even from that age, when we were awkward, pimply 13 year olds, he also was like a total night owl. So he'd stay up and watch 120 minutes and like have all these recommendations. That's how I found out about Aphex Twin, the “Come to Daddy” videos on, you know, 2am on MTV.

[sirens in background] Sorry for the sirens here. It's Brooklyn after all.

And yeah, I think that moment must have been late '97. Discovering Aphex Twin was kind of the catalyst for discovering electronic music in general. Or that was my foot in the door, so to speak. I was obviously aware of that sort of thing. My older brother was pretty active with Detroit raves and drug culture and super into Plastikman, which at the time, I thought was…it didn't resonate with me. I love that stuff now. Richie Hawtin's awesome.

But yeah, after kind of developing my sense of what you could do without a guitar at that age, I just dove headfirst into Warp Records and, yeah, just less mainstream…like, I had developed a sense of how to find my own stuff, and so you know, Eno and Velvet Underground and Mogwai and Boards of Canada were all just like my favorite things. Obviously kind of all over the map, all very renowned. I know those are fairly cliche, but they were all very deeply influential.

And especially someone like Brian Eno, when you're talking about the dichotomy of like, pop versus more meditative stuff, he was a huge inspiration for that - not pigeonholing yourself. And honestly, Aphex Twin, too, because "Come to Daddy" is worlds away from "Selected Ambient Works," you know? But it's the same individual with the same kind of cheeky sensibility doing that work. And so that sort of gave me the confidence, I would say, to just feel things out naturally.

And I always liked writing songs. I think probably my biggest songwriting inspiration at that age might have been Phil Elverum. Those first few Microphones records were a huge deal for me, speaking of texture and production.

I remember reading an interview where he described getting one particular percussion sound by wrapping a microphone in a plastic bag and dipping it in a bowl of water, or something like that. You can literally just do anything you want to make a sound, and at that point…that was at the point that I was recording on a four track cassette player. I would try to get as many instruments into a piece of music as I could over the course of three or four minutes, and just do hot swapping tracks while I was mixing down to a tape on my shitty Aiwa 3-CD changer stereo that everybody had in the late 90s. And yeah, it was a lot of fun.

I'm grateful that I had that drive and that experience, and then frankly to have parents that were encouraging of that, because you know, my mom's an old hippie. She was the one that got me into piano lessons because her best friend was - she's retired now, but was my first piano teacher. And as soon as I showed interest in that, she just let me do whatever I want. My dad was one of those dads that kind of shows his love by buying you things. So I was like, “I want a bass guitar.” He's like, “all right, let's go get you a bass guitar.” “I want a drum set.” “Let's go get a drum set.” Huge leg up there, for sure.

Pretty much since I was like 13, I've been recording original stuff. My first recordings are in a box in the other room that I will never show anybody, because they're just like, the shittiest possible covers of…

Andrew: Challenge accepted.

Tom: You know what? Yeah, maybe one day I'll dig them out, but I'm almost afraid to listen to them. In any case, that's a very long-winded way of saying it's always been a pursuit of an organic sensibility about things.

Andrew: Yeah, and it comes across very clearly. I mean, I think there's…it's a very distinct…you know you're listening to *you* when it comes on, I guess, and it just strikes me as a very distinct style. So it stands out, I think, in the crowd that we're usually lumped in with, and it strikes me as something that is very thought out and methodical in approach.

Tom: Well, thanks man. I've tried to…I have the simplest set up you can imagine. I mean, you've been on tour with me, so you can see my pedal chain has pretty much been the same for a very long time.

And as far as production techniques, I have just a minor variations on a bunch of different tape decks and the way that I record them. People, a handful of people, have asked me over the years how I get the certain kind of environment with guitar loops that I do. And it's really simple. It's one track of taped guitar loops and then another track of clean, direct signal and I just blend those together. And I have no problem sharing that technique because, for one thing, it's something you could easily figure out on your own, but also, whoever employs that is going to do a different thing, no matter what. And it's going to end up sounding different, which is something I appreciate.

One of those things from film school that I always thought was interesting - I can't remember who the film theorist was, but the idea was that “information wants to be free,” basically. And that you should, if you're in a creative field, you should have no problem sharing every detail of what you do because, again, those rules put in someone else's hands are going to yield a different result.

Andrew: I couldn't agree more. Yeah. I mean, I think we all learned to do what we do from some extent by watching and copying other people that we admire and respect. And it's, I don't know, I don't see the benefit in being closed off about this stuff. I'm right there with you. It doesn't make sense to me to not share if people are interested and curious. I think it's totally fair game to open that door a little bit and let them in.

Tom: Yeah, but in my case, speaking of the limited palette or the limited kind of setup that I have, it's important to me in making things that I know how to get the sounds that I want. Especially when i'm making more elaborate guitar/vocal/percussion songs, having that set of tools that I'll reorient and create a different sounding composition altogether. But I don't know, like working with Raf [Rafael Anton Irisarri] on the Orcas stuff is a totally different experience because he's a wizard, for one thing. And I, for years, like I've known him for 15 years at this point and our last record came out 10 years ago already, which is crazy.

And by the way, we just got masters [for a new Orcas record] but they need a little tweaking. I'm sure you'll hear them soon.

Andrew: Oh, amazing. I can't wait.

Tom: Yeah, that song you played on, it's in the running for a single. So we'll see how that goes. But yeah, since I've been working with him, since like 2009 or ‘10, I've always had in the back of my mind, “this is the year I'm going to learn Ableton,” and it just never happens because it spooks me. It spooks me when I see how much you can do with that, and I would just go down endless rhizomes of treatments and and side chains and all that sort of thing. That's how you get some of the most interesting sounds, but it's also kind of comical when Raf gets tired of working on one particular thing [in Ableton Live], and he'll just whip out a song in five minutes [without it] and it's the best sounding thing you've ever heard.

Andrew: Yeah, it's a dangerous game you play, in that the more you know, the more you think you have to do, and I think there's a real beauty and power in staying simple. So I have nothing but respect for guys like you who can just recognize, “this is what I need. This is what I'm going to use. I'm just going to do it.” I'm the kind of person who will very much spend, way too much time in the details, and forget about what it is I'm even trying to do after a certain point. So, I think that's a really important thing to be cognizant of.

Tom: Yeah. One thing that is kind of a drag to me, though, is the fact that I put a fair amount of effort into getting certain sounds from tape machines, and I'm familiar enough with my Marantz to know when to bend a pitch or whatever…it's all very manual and tactile. But there are so many…I think you even shared a video or a capture from something you were working on with one of the tape emulators. And those things sound so good, I can't fake those (no pun intended). And it's probably way more controllable even than a real tape. So, however you get into it. I mean, like, AI and emulation is a totally different conversation.

Andrew: Yeah, I think it's…there's so many options these days. It's really all about about comfort. I was talking about this with someone who asked me sort of a related question, just about stuff that I use. I said I still think that, for all the things that are available to us and everything that we can use these days, with how good software is, it's still…I think priority 1A is just making sure that you are comfortable and confident. And if you need a piece of software to feel that way, that's great. If you prefer to use a physical tape deck to do that, have at it. Like I said before, just accepting and knowing what you prefer amongst an ocean of possibilities, I think is really important, especially these days.

Tom: I could be fooling myself to a degree, but I do feel like you can kind of innately sense when something is fully analog versus treated. Like, I mean, I'm sure I'm not the only one who feels like he can instantly pick out a MIDI sound. I think the most grating sound in the world is MIDI strings out of the box, or MIDI woodwinds if you don't treat them at all.

Andrew: It’s really easy to mess that up.

Tom: Maybe my perception of that is outdated. ‘Cause I know there are vastly updated versions of MIDI [instruments]. I've heard piano emulators that sound very convincing in recent years, like even down to the Nils Frahm “you can hear the hammers on the strings” kind of thing.

Andrew: I have Nils's piano library, Noire, and I use it constantly. It's by far, in my opinion, the best sounding software piano I've ever used. I don't feel a need to buy anything else at this point.

Tom: It is kind of crazy that as a traveling musician, you can pretty much carry an entire - what used to be an entire U-Haul truck full of stuff on a laptop these days.

Andrew: I love it. I have a 200 pound Rhodes piano sitting behind me and it blows my mind that people used to cart those into vans and load them onto stages night after night on tour. And now I can literally pull out my phone and play a Rhodes software instrument that sounds just as good. It's just incredible to me.

Tom: Yeah. I don't know if she still carries it with her, maybe it's only when she's playing near Astoria, but Liz Harris - I've played a few shows with her where she had…she needs at least another person to help her load out the huge thing and get it on stage.

But, respect. I mean, again, there's nothing like playing the real thing, feeling the keys and all that. But if you’re just going for pure sound, yeah, there are other methods.

Andrew: Absolutely. I wanted to touch on something. There's a couple of different ways I wanted to go with a lot of the points you just brought up, but you did bring up Raf and the work you do with him in Orcas. And I know he's kind of your - he’s one of my “go-tos” as well, in terms of mastering and mixing assistance. I know he's pretty involved. How much outside influence do you pull into your own work? Do you think about soliciting feedback first, or is that only something that you do if you feel like you really need to do it? How self-guided in your decision making are you with your music?

Tom: These days, yeah, I guess…historically i've always just worked all the way through to the end of a piece and then shown it to people, and so maybe there's mixing feedback, right? Raf is certainly somebody I trust more than just about anybody else, in terms of that kind of feedback, and also I think - coming back to my limited sound sources, palette, whatever you want to call it - that's something that frustrates him a bit because 20 years on, I'm still kind of an amateur and I use GarageBand for everything.

And when we were mixing the record I did for Morr Music last year, the one called Eidetic, I mixed everything myself and then took it to him just to basically sweeten and master it. And he's like, can you give me stems for all of these songs? And I'm like, “no, there's 17 songs with like 20 plus parts each. I'm not going to stem all that out just so you can mix it.” I mean, granted, I'm sure his mix would sound amazing, but that would just…that would be another several weeks of work that I can't pay for. There's a certain aspect to the autonomy or whatever, the auteurship, if that's the word, of having control over the mix. That’s part of what I want to express in the songs.

I think it's become, to my understanding, it's become kind of a mark of my vocal work that the vocals are in a certain place in the mix, that they're just slightly out of intelligibility a lot of the time, which is counter to the fact that I spend so much time on my lyrics. But it's just part of it, in that I don't consider myself a singer first and foremost. It's just something that comes in there because I get…I feel lucky that I get melodies running through my head all the time, and sometimes they come first. Sometimes there's the chord structure in place and something will just settle into that. But, that's one of the funnest things. Bass lines are still my favorite thing to record in those songs, but, they're also, again, they get kind of buried in the mix there, but for the most part everything gets assembled, baked, comes out of the oven, and then I get feedback at the point that there's nothing I can really do.

But I will say, for example, if you look at my Bandcamp page more recently, like chronologically in the last five years or so, there's been a lot more collaboration. And I feel like I'm at a point where that's a natural evolution from doing things totally solo for so long. I've collaborated here and there over the years, but there are more people in my orbit, for one thing, I guess, in the last little while.

I'm honestly kind of surprised that we haven't worked together really other than like, you know, compilation stuff.

Andrew: I know, we’ve got to correct that.

Tom: I did one track with Steven [Kemner] for a compilation at the beginning of lockdown.

But working with Boris, Jogging House, the other year - that tape came out really nicely.

Just like in the last couple of months, I've put out records with zakè, Zach Frizzell, another human angel.

And then offthesky, Jason Corder, who I've liked and been…we've sort of been in the same circle for at least 10 years at this point. I've known about his stuff. I think we played the same festival in Denver in like 2015, but I knew his stuff before that. And yeah, working with him was great. And Laaps, the French label, put out a really beautiful package for us.

Andrew: Yeah, I love that new one. It's so good.

Tom: Oh thanks. Yeah. But you're speaking of the weirdness of 2020 and ‘21, and I still feel like the influence of the insularity of that period is still enacting itself. Like, I only just worked with Luke [Entelis, AKA Viul] in person for the first time two weeks ago, when we were finishing a piece for Past Inside [the Present], a split 12 inch. He and I made this 20 minute piece that was ambitious, but I think came out well. I like it anyway. It's never for me to say whether it's good, but it was what we wanted. And it's very different from the record we did for A Strangely Isolated Place.

Anyway, that was my first experience, basically, collaborating in person with somebody since lockdown, other than Raf. Which counts, of course, but I just got it so in my head during that period that like, “well, this is just how it's always going to be now, no more tours, no more in-person sessions,” and it's tough. That’s tough to extract yourself from.

Andrew: Right. I was talking about this with someone else the other day too, but yeah, I feel like 2020 hit, there was an initial shock, everyone kind of retreated into their little ambient/drone shells, and there was a ton of music coming out at that time. And then at a certain point, I don't know exactly when, but it just feels like all of a sudden the number of collaborative releases - across all genres, really, but especially in our little ambient world - it seems like the number of them just exploded. It felt like everyone was reaching out to everyone. I know I did a lot of work with other people, too, after that time. And I feel like it kind of opened people's minds to that possibility after being locked down and shut in for so long. It does feel like there's a little more of a collaborative spirit in the air these days.

Tom: Yeah, it might have come down to the baseline knowledge that most people you know aren't really up to much.

Andrew: Right, exactly…how different could their life be from mine at this point?

Tom: Yeah, that's part of the reason - I know you weren't recording earlier when we were talking about my career shift - but lockdown stopped me from being able to work in service and work in live performance, so that I'd barely scrape by on passive income and was really trying to hustle self-released stuff during that phase. I got a little bit of help from family that I'm grateful for, but yeah, it really sucked.

And that's part of the…that entered into the decision to have a more stable career. So, going into teaching makes sense from that perspective. Getting married in a few months and having an eye on, you know, getting a house upstate one of these years, eventually…but yeah, it's just like, I'm sure I'm not the only one that gained a different view on what it means to be stable and whatnot. You think there's always going to be service jobs, but then for a year and a half, there just…weren't, or at least not safe ones. Do you really want to be an Uber Eats driver? Yeah…so that's, it's been a long time coming, and there are silver linings from lockdown, but I wouldn't do it over, I would say.

Andrew: Yeah. And speaking of New York, where you are now, and lockdown: correct me if I'm wrong and I'm getting the timeline wrong here, but I believe you moved out there right before COVID-19 hit.

Tom: Yep, that's accurate. Yeah, August, the August before. So I was here for like seven months or so. And I was in Seattle for seven years, almost, before that. It was a big change. I came out here, I had saved up a little bit of a nest egg to live on, and I was like, “I'm gonna give myself six months to familiarize myself with the city, go to a bunch of museums, figure out all the best bike routes in Brooklyn that I can find.” That sort of thing. “And it'll be a blast.” It was…those first six months were very, indeed, very fun. And then all of a sudden, I was thinking like, “all right, the coffers are getting a little tight right now. I need to start having a regular income.” And that's the point [when COVID-19 hit] that it's like, “all right, I guess I'll just play animal crossing all day.”

Andrew: I wanted to ask you how that move to New York specifically affected - if it did at all, I don't know if it did - how did that change your creative process? Does your studio in New York look a lot different than your studio in Seattle? Or even with your surroundings and your environment, does that come into play in terms of what you're making, when you're making it, how you're making it? I'd be really curious to hear how the “New York Tom” differs from the “Seattle Tom” creatively.

Tom: I mean, the proximity to nature, I think, did have its influence in Portland and Seattle, for sure. You know, I spent more of my days off taking a picnic lunch to the beach in Seattle, for example. But you know, there's a beach here. It's a different one. And there are a few forests, believe it or not, nearby. There's one in Queens that's like, I don't know, maybe a 25 minute bike ride for me. It's huge and pretty quiet, and has a really nice trail system, so I spend as much time there as I can. There's also Prospect Park, it has a pretty huge forested area in the middle of it, and a nice little lake with swans and so forth to sit by. So it's different, but there are resources - natural resources - around here.

Gosh, as far as changes in the music, I don't know. My techniques are so entrenched in what I do that I don't feel like that's had a major influence. The one major alteration I made is when I was recording Eidetic in ‘21 and ‘22. [For] the main sessions I wrote everything at home, itting on the couch, you know, just working everything out. So writing was all at home, but then I booked a super cheap Airbnb cabin in the middle of the woods in Maine for two weeks in March of each year, ‘21 and ‘22, and recorded about half the record each time.

I actually - this is one instance where I got a very significant piece of feedback from both Molly, my partner, and Raf. I went up there for that first trip in 2021 for two weeks and came back with, I think, seven songs, and a bunch of instrumental stuff. And it was cool; I was satisfied with that. I had a 42 minute record that I felt was ready to go, and Molly was like, “what if you did five more songs?” I was like, “I don't have five more songs…” and she was like, “well, just write more.”

That's a funny thing about Raf, because he makes incredible music, but he's not a songwriter, so to speak. And he thinks there's some infinite well of that, but all it took was for the two of them to be like, “no, you should aim higher and make a full record,” similar to the early ones that I did for Kranky, rather than have strictly half ambient, half vocal.

So, consequently, I spent the next three months just zoning in, and wrote what I would say are my favorite songs on the record. I just kind of went off that energy. And then booked…I was like, “well, the first trip to Maine went really nicely. Might as well do that again when the time comes.” And sure enough, I did the same thing the following year, at the same cabin, which had no running water and a little outhouse for me to use. It luckily had a heater and wifi, which is all I really needed. And pretty reliable electricity. There was one ice storm that took out the electricity for a day. That was fun.

Andrew: On behalf of all of us, I'd like to thank Molly and Raf for encouraging you to add those additional songs, because yeah, I think that is 100 percent one of your strongest records to date. And I remember, I think you shared some of the early demos with us, or I think they were close to finished mixes at that point, when we were in the tour van driving through God-knows-where in California.

But that was a really beautiful record. And I really think that you benefited, artist to artist here, it seems like that time was really fruitful for you, the time that you got to spend up there in Maine working on that.

Tom: Yeah, it sure was. I benefitted from the - well, it was just a total lack of distractions. There was nothing I could do there. I would leave the cabin every 3 to 4 days to go get more firewood and groceries, because the grocery store was like 17 miles away or something. You know, there's no town, no nothing. It was pretty great. Just a creek running outside.

And yeah, I would say that, other than maybe “Lasted,” which is the record I put out in like 2010, “Eidetic” is probably the record I consider the most exemplary for what I want to bring into the world, essentially. There's a balance. There's an interjection of ambient stuff in there, but those are the songs that I feel are most meaningful. And honestly, maybe it's just me getting older, I imagine, but I can't imagine how I made a vocal record every two years for a while, because this one took seven years. And consequently, I feel like it's more fully fledged, if that makes sense. I put a lot more time into the lyrics, and the subject matter came from a lot more meaningful life experience. My first record for Kranky was basically a breakup record, so it was just sad sack 21-year-old romantic Tom. And this record has a lot more about family and loss and grief, and more profoundly felt emotions, I think. And it consequently felt like that much more cathartic to have it finished and out there.

Andrew: Yeah. That actually brings up a point that I wanted to ask about in a slightly different way, but to kind of piggyback on that thought. When you go through a process like that, you've put a lot of energy and time into something and then it's released out into the world…where do you go to recharge from an experience like that? I know your Polaroid photography is a big part of what you do, and you're also involved in a lot of different collaborative work. But how long does it typically take you to recharge yourself after an experience like that, and you put so much energy and time into something? Are you even thinking about the next solo thing at this point, or do you think you're going to need more time to do that? I'd be curious to hear your perspective on that.

Tom: Well, right now with a wedding coming up and master's program coming up, I'm giving myself the space to not worry about that. But still making things. It bears mentioning that I've got that bandcamp subscription thing. So most of the music that I put out- I put out at least one new song, generally one, sometimes two, new songs as an exclusive for the people that subscribe to me on there, who I'm hugely grateful for ‘cause they pay for my groceries, at least, every month, and some of the bills here. That's a big deal and it's not lost on me. I try to make it worth their while.

Subscribe on Tom’s Bandcamp page here

That also allows me some freedom, like, if I just decide I have a free afternoon and I don't have anything else going on, I'll just step into the little studio space I've got and make something and [share] whatever comes out unless it really sucks or something interferes, or there's something off about it. It's generally at least worth sharing as a kind of view into the process. I guess if that makes sense. Yeah, but as far as the question about recharging. Yeah, I don't know. It's the that's another thing that I feel like has to come from a sense of intuition. It's like, you know, when you feel like it and you generally kind of know when you don't, I used to get really bothered by, uh, ruts in between recording or like if I wasn't feeling inspired or I was, you know, I was like I want to write a song this month like by the end of the month if I set that goal and I Didn't meet it or whatever came out was just half baked.

I get really disappointed, but I've come to be a lot more kind to myself about the fact that there are peaks and valleys of that and having something like photography as a similarly soul-feeding pursuit…there's a better way to say that, but something that I enjoy doing to express a similar passion for analog aesthetics, and that sort of thing.

That also allows me to deduct supplies from my taxes. I mean, I still have… I'll go into photo mode especially in the spring and summer when the light is better, because especially using Polaroid it's a little more temperamental. Molly is also an analog photographer. She's got a Yashica and a really nice, old Nikon 35 millimeter. We're actually shooting, planning to shoot press photos with Raf next weekend, which will be fun. He's always…I don't know. [laughs]

Andrew: It doesn't strike me as something he would be thrilled to do.

Tom: It's not his favorite. I was trying to think of a kind way to say it. Looking forward to some scowls.

Andrew: If you're listening, Raf, we love you.

Tom: So yeah, having multiple pursuits. I mean, I'm also like, I spend a ton of time in the kitchen as much as I can too. That is as much a creative expression as anything else. Finding new recipes, improvising, that sort of thing. And it's also, that's an act of caring that means a lot to me. I took one of those Enneagram tests and it labeled me as a “caretaker, “ like as my primary trait, which I feel is fairly accurate.

Andrew: Yeah, definitely. Yeah. I think I'm a nine on the Enneagram. I can't remember what that correlates to exactly [it’s a Peacemaker], but I do remember the number.

The Polaroid stuff though - I wanted to ask a little bit about that. It’s almost to me, like, an inherent part of the music. When I hear your music, I almost think of your photography in the same kind of instant, you know. The music sounds like the Polaroids look, and I think they're so linked in my head that I almost think of them as very much partner art forms.

I'd be curious to hear your perspective. How much do you separate those two things from one another? Because I know they often find their way, the Polaroids, into album artwork or little ephemera that comes packaged with the releases that you do. Do you see any distinction there or do you view them as almost like a joint artistic practice for you?

Tom: Yeah, I think it's a side of the same coin, I would say. And that means a lot to hear. Thank you, I'm glad it resonates in that way. Because it, yeah, it makes sense to my brain. I've always had a very “integrated” audio/visual brain. That's part of the reason that I pursued film in school, because film and images and sound just make sense together to me - not quite to the point of synesthesia or anything like that, but yeah, it's always been the case.

I think even though almost all of my record covers, with a few exceptions, are Polaroids that I've taken, I'll even be surprised by which ones come out, and I'm like, “that one has to be the one.” Even with Eidetic, that doesn't really look like any of my other records, but there's a combination of the softness of it and the fact that I took it from this little bridge over a creek in a park that my dad and I used to hike in when I was a kid, and it was at the time that he was sick and he passed last year. So, you know, it becomes all the more meaningful.

I've tried to always keep that sense of posterity in mind, which has a lot to do with, you know, the look of old photos can especially…certain Polaroids come out and they immediately look like they're 20 years old, which I love.

I never really took portraits of people until after my brother passed in 2016. I realized I didn't have a good photo of him, and that made me sad, so I resolved to try to get as many portraits of people as I can. You've let me take shots of you and the other guys on tour. Some of those came out really nicely. I love that photo I took of the three of you on the cliff side in Big Sur. That was pretty awesome.

Andrew: me too. It's still one of my favorites. Yeah. I'll have to include some of those in the the article that I post this with on my, I'll make sure to include some of those photos.

Tom: Yeah. And so, yeah, in the other room in our bookshelf, I've got like a whole shelf of binders of all my Polaroids, some like the, there was the book that I did for the Morr Music publishing arm a few years ago for the Sylva record. And another whole book's worth that I wanted to publish alongside Eidetic, but they didn't have the budget for not to slag them off, but it's not their fault.

I think it was exorbitantly expensive to do a short run of books like that, but I'm very grateful for the one they did. We just have to figure out what to do with all the shots that I've got, for what was supposed to be the next one.

And then I've got a few other binders of ones that I've kept over the years from traveling and touring and various other experiences. I've got two whole binders of just people at this point. And that's - I hate to keep harping on lockdown, but during lockdown, those were a nice resource to have on the shelf, just to pull down and remember all the good people in my life that I don't get to see, necessarily, but that are still there. And it was a good motivator.

It never costs you anything to send somebody a text when you're thinking about them, or give them a call or whatever. It always means a lot to me when somebody randomly just reaches out, and is like, “Hey, this made me think of you,” or just like “hope things are good,” even that sort of thing.

Andrew: I’m right there with you. Yeah. It's weird, because it's never been easier to reach people, but at the same time, I feel like it's almost because of that that we take it for granted. And I think it's actually kind of psychologically more difficult to remind ourselves that we do need to do that more often.

Tom: Yeah, so it all, I guess if we're looking for a connection of everything here, it all comes down to documentation. That's something I'm really grateful for at this point, being almost 40, that I've got diaries or journals, whatever you want to call them, going back to age 13 or 14. Again, probably not something I want to revisit unless I'm prepared to cringe a little bit. But there's, you know, there's journals, there's all the boxes of tapes that I've got from over the years. There's the records that I've properly released and have had released for me by some of the nicest, coolest people in the world. And then there's my, you know, books of photos.

I'm gonna have a lot of crap that people need to get rid of when I die, but I love having it all around.

For me there's a vain pursuit of continuity in life. For one thing, I don't understand how people get through life without some kind of creative expression. No slight to anybody who doesn't actively work creatively, but I don't know who I'd be without that stuff. And I've been very lucky to have anybody care at all.

Looking back on certain things, it's weird to consider that I was the same person that made certain things that I have made. There are certain records and certain songs that I listen back to occasionally and don't…I have no memory of making them. Which, that brings up a lot of philosophical, existential questions that we don't have to get into here.

Andrew: Yeah, absolutely. I wish we could. I wish I had all the time in the world.

That brings up a funny point. I think I was talking to Taylor Deupree about this one time, but he was saying something to the effect of, “I don't enjoy listening to the work that I make until I forget how I made it.” Cause you're almost like, you're thinking about all the things that you could or would do differently in the moment, because you remember the specific things that you did when you were doing it. And there's almost like a certain level of detachment that has to come, and I totally agree with that. At least for me personally, it feels like I need to let it live on its own for a little bit and step back, and then listen to it later before it comes into full focus. It's an interesting thing to think about.

Looking back at some of the things I've made in the past, I don't really recognize who that person was or what they were going through, but it's still really interesting to have that documented in some way.

Tom: This this makes me think of I think mostly in like late high school, um, I totally idolized Harmony Korine, the film director. At the point that like Gummo and Julien Donkey-Boy came and he made this record in, I want to say '99 with Brian DeGraw from Gang Gang Dance called "SSAB Songs."

And it came out on the short lived record label that Other Music ran - I think it's called Omplatten - and it's this 27 minute thing that plays this one single track, but it's just a bunch of little movements and experiments and living room recordings that I totally loved, just because if you're speaking about cross-pollination in aesthetic, it perfectly expresses the album version of Gummo to me, which I know is a very divisive film, but it's one of my favorites.

And I remember reading an interview with him, with Harmony Korine, a few years after that came out. And I think the interviewer asked him, like, “how do you feel about SSAB Songs these days? Are you going to make another record?” He's like, “Oh yeah, I never even listened to that one.” Like, “I just made it and shat it out.”

And who knows one of those people, like, you know, Aphex Twin and Lou Reed, where you never know how much truth they're actually telling. That's kind of, part of the appeal. But I like that idea of just, “yeah, we're going to make this record. Sure. You can release it. No, I'm not going to listen to it.”

Andrew: Totally.

You brought up some of the portraits that you've taken when we toured together, and so I was thinking about the next question to ask here. When we have toured together, I'm always impressed and struck by the way that you can always sound like you, regardless of the room that we're playing in or the lineups that we've been a part of. We've seen a huge range of places and experiences together, but it's still like, it's still undeniably you, I think, when you play, and there's a very distinctive trait about your music that always comes through, regardless.

So I'm curious to hear you speak about how much of your set is improvised in the moment, or adjusted to fit the space that you're in or the people that you're around, and how much of it is like a pre-planned exercise. Do you think it's like a- do you go in with a well-rehearsed set that you're trying to execute, or do you leave yourself room to make adjustments as you go?

Tom: Well, again, I appreciate that. So complimentary.

I mean, it's a combination of all that. There is…yeah, generally, especially if I'm going on tour, I try to have a couple of variations on a set ready to go. The biggest asset, or the only time I really majorly changed my live setup, is when I discovered and bought the Electro-Harmonix EHX 22500, not the most memorably named pedal, but it's this great little sample rig you can operate off an SD card.

There's a ton of memory, and you can basically loop something for as long as you need to. I put entire ambient pieces on there, you know, 10 minute things, if I want to just walk off stage at the end of the show and leave something running. Because I've never used a laptop other than maybe like my first couple of shows back in 2006 when I thought that was the thing to do. But other than that, it's always just been pedals and voice.

But yeah, part of the reason - and it's always been my excuse - for not putting together a small band to play my songs is that I really like the ability to adapt and improvise and go off the cuff. If there's a section that I'm working with guitar improv, or something that's working out particularly well, I can just roll with it for a while and let myself feel out the pacing a little better.

Generally, I would say my live sets are structured based on the vocal songs that I want to play. I'll usually have six to eight of those prepared, and do four to five during a given set if it's 45-50 minutes…that sort of thing. My favorite set length is, like, 35 minutes, but you know, sometimes they'll request that you play a certain amount, so whatever. Being able to improvise and decide that I only want to play one song sometimes is a nice way to have it.

And I do also generally have - my maps are more like flowcharts in how I have the set together. It’s like, if this setting on the 22500 is in this key, I could connect this song to that one, or I could go over here…it's pretty “choose your own adventure,” which makes it fun. And especially - it's been quite a while since I've done like a longer tour; my last actual multi-week tour was in 2017 in Europe, but when you're playing 20 shows over a few weeks, it keeps it interesting to be able to change it up every night.

And honestly, one of my favorite shows, for a lot of reasons, that I ever played…I can't remember the name of the venue…but it was in Toronto the night before my brother's funeral, weirdly. Obviously very heavy energy on my part, but he passed before I was going on this tour. I wrung my hands and had a long talk with my mom about whether or not I should even play the first few shows, because it was like, he died on March 6th of that year and I left for the tour on March 9th. I had like five shows before I got to Michigan, where she was - my mom. And I was like, “I could just come straight to Michigan.” And she's like, “you know what, I think you should try to play the first couple of shows, see how it feels. And go from there.” And sure enough, it was exactly the catharsis I needed. Because there was nothing to be done, you know? He had passed, he was cremated, and his service was a couple of weeks later.

So it worked out that I did cancel, I think, three shows in the middle after the Toronto show, but the night of the Toronto show…this was preordained, but they had it set up in such a way that they told me not to sing. The whole idea is that these are shows where the performances are instrumental, and the people attending are not allowed to talk. They give you a little stack of index cards and a pencil when you go in, so if you want to say something to somebody, you write it down and pass them the index card. They write their response and give it back to you. And I just…I fucking let loose, like I played the loudest “Ben Frost guitar” set I've ever done. Total one-off, not recorded. I just felt it out. I faced the wall the entire time. I think I probably cried. I finished and took a huge breath, and at the time I was smoking so I went outside and probably had like five cigarettes afterwards, and then went home and had a very emotional experience the following day and a few days afterwards. But, yeah, that show is like the perfect example of how sometimes it can be the greatest outlet in the world to just…I would have done that by myself, but having a room full of people to experience that with was particularly meaningful.

And it is…it's nice to work in multiple modes, to be able to adapt when they're like, “could you just do an entirely instrumental set?” And, yeah, totally. Sometimes there's less pressure when that's involved. I'm not a trained singer. Sometimes my voice doesn't want to behave. If I forget that I’m playing in an hour and I have a slice of pizza, the cheese can make me sound weird.

Andrew: Yeah. My wife was a theater kid growing up and she's a phenomenal singer, but I've seen all the tricks that they do, the lemon drops and throat coat stuff. Yeah, taking care of your voice is - that's a legitimate, full time, conscious thing that you have to work at, to keep it ready to go like that.

Tom: I used to be very bad about that. The first national tour I did in, like, 2010 when I was by myself, driving 10,000 miles around the country, I think I was just intoxicated by the very fact of being on tour and being out on the road and alone. Like having people show up to see me, I mean…I was playing shows for, you know, 20 or 25 people, nothing crazy, but it was just, yeah. I was smoking lots of cigarettes, drinking lots of whiskey, barely sleeping a lot of the time, and not doing any vocal exercises, so I'm sure I sounded like garbage certain nights. But who knows? That's long in the past, I'm sure nobody will - hopefully nobody remembers.

But over the years I got a lot better. I think what really kicked my butt into gear with caring a little bit more about that was the year…it must've been the year after that, when I went out with A Winged Victory for the Sullen and Ken Camden. Adam Wiltzie is one of my guitar idols, so when he asked me to do that tour, I was like, “all right, better get my shit together.” Started learning how to properly do a vocal warmup and that kind of thing; learn to breathe better from the diaphragm and all that. And that set me up for knowing how to do that on future tours. I feel like not being a natural performer, it certainly helped me elevate my performance standards after that.

Andrew: Yeah, that would incite me to get my act together too. That's a…he's a hero of mine as well. So I resonate with you there.

Tom: That was a very fun trip. That was another one where I feel like I generally brought my best. There's only one show on that tour that I remember really being down on myself because, I don't know, just technical issues and so forth. But in general, I feel like I was the most consistent on that one.

I assumed across the, whatever, two and a half weeks we were on the road, that they - at least it was possible that Adam and Dustin weren't paying attention to what I was doing and [were] just preparing for their own set, but I remember I had this distinct feeling of absolute joy when we played our show at the Triple Door in Seattle. I finished my set, went upstairs to the green room where they have the sound piping in, and Adam was just sitting there on his phone, but he looked up and he goes, “that was your best set of the tour.” And I was just like, “Oh my God, thanks dad.” It's like, you know, in that moment that he had been listening and he actually had positive feedback; it was great. And that's all he said, ultimately. But, of course being 26 or 27 at the time and having a lot of self doubt, and being in the presence of someone that I really wanted to impress, I just was like, “man, what if he hates it? What if he totally regrets bringing me on the road?” And yeah, maybe he did, ‘cause we haven't toured since then. [laughs] But that was my…that was a total blast. A very fun trip. And especially, the ladies that played strings with them became good friends of mine too, after that.

Andrew: Yeah, that's awesome. I think it actually leads into the next question that I wanted to ask, but I mean, you've been able to work with a pretty incredible range of not just collaborators, but touring partners as well. I know you've done a tour with Scott [Morgan] as Loscil for the Kranky 20th anniversary thing a couple of years back. You've, like you said, you've been to Europe a couple of times. You've done stuff with Windy and Carl, stuff that to me that is like ”off the charts” cool.

So at this point, what do you think is next for you? We've talked a lot about your collaborations and we've talked a lot about your recent solo work, but are there projects out there that you haven't really explored as much as you'd like to? Are there tours that you would like to do in the relatively near future? Granted, you've got a lot going on in your life, but I mean, what do you foresee on the road ahead? Are there things that are you're really dying to do at this point?

Tom: Yeah, I mean, these things kind of appear sometimes. They materialize. Sometimes you have to seek them out.

But I was in the process of planning a tour last October and it just kind of…I don't want to go so far as to say “it fell through,” but it just didn't feel like the right time, especially in the wake of my grieving process after my dad passed and various other things, like deciding I wanted to have a career shift. I was just like, “I'm not going to be able to bring my best to this.” So it kind of got postponed and it hasn't really been reformulated, but I definitely, you know, I would love to do a proper tour again at some point, I think, at this stage, being my last full U. S. tour was eight years ago…which is kind of crazy to think about. But I think at this point I'd want to limit it to more like two weeks. I think that's a good length for a tour. Five weeks is just too much. Plus, granted, everybody's mentioning it but I believe the entire universe of touring has shifted, not only because of COVID, but it's just like, the whole music distribution system has shifted.

I'm not really big on merch, which I know is how a lot of people fund their trips. Venues are less receptive to smaller draws these days, it seems like, and that's fine. I feel like I've had a ton of extremely valuable, memorable experiences touring, and I feel infinitely lucky for that. But whatever comes together with that would be great.

Raf and I have talked about playing some shows for the Orcas record, which knowing the complexity of the material, would involve a lot of work. I would very much like to do that at this point. I don't want to speak too soon, but we…the record should be out this year, hopefully by early summer, but it's moving again. We just got masters, so usually it's at least a few months beyond that. I feel like that's the most likely next step is that he and I will put together some kind of live thing. What sucks is that we lost a lot of the original material for our first two records because all of his stuff got stolen in 2014 when he and Rita were moving from Seattle, like literally their entire U-Haul truck got stolen the night before they were about to leave with all of his hard drives, all of his shit. So yeah, those first two Orcas records are basically gone. And if we wanted to do any songs from those we'd have to re-engineer them, essentially, like re-record whatever we wanted to do or re-imagine them. Which could be fun, but again, it would be a lot of work.

So, I've got that in my sights. It does feel a little bit daunting at this point. Cause [Raf’s], you know, he's like my older brother. We refer to each other as brothers. And he always comes from a place of caring and just wanting me to do my best and perform at the level that he knows that I can. But he's also a pretty demanding director. And again, it comes from a place of love - that's not a dig or a negative thing. It's…ultimately, I sometimes need somebody like that to push me a little, to a higher level, you know? So I know that would have a lot of demands for time and energy.

And you know, luckily that's part of the reason I moved out here, honestly not only for Molly, but for being close to his studio. And so the fact that I can get out there in an hour on the train, it makes it less daunting. I think if I were still out West, it might not even be a possibility.

And other than that…yeah, I've got the Orcas record coming out. I've got a much smaller release, a lathe cut for Whited Sepulchre Records coming out in a couple months.

Andrew: Yep. Great label.

Tom: Molly's doing the artwork for that. Yeah, Ryan is amazing. And then beyond that I've got something cooking with Zach Frizzell for later in the year, too, but nothing has been announced so I shouldn't say anything about it. Not a huge deal, but there's a couple other instrumental things on the way.

Mostly just focusing on avoiding a midlife crisis at this point.

Andrew: No small feat.

Tom: Yeah, I've got a lot to be…I'm trying to focus on what I've got to be grateful for. I feel like I passed through a dark tunnel last year, like a lot of people, and the light is looking pretty bright right now. So I'm grateful for that. Just pushing on, keep staying responsible. I'm really glad to be sober now, and making good changes and good choices, and got a powerful level of love and gratitude in my life, which, you know… that comes in waves, too. It's similar to creativity. But I'm trying to avoid being the kind of person that thinks, like, “Well, when's the other shoe gonna drop?”

For now, pretty good.

Andrew: Well, after the last couple of years, I don't feel like anyone could blame us for thinking like that.

Tom: And again, yeah, it's a very separate conversation that doesn't really carry over here, but it's hard not to think about November too, and especially if I go to work for the school that's primarily serving underserved communities. This whole political cycle is going to be very relevant. It always is, but particularly so.

Andrew: I was on the phone with Marcus [Fischer] last night and we were talking about the work that he did for the Whitney Biennial a couple of years ago, that Words of Concern piece that he did, and it just feels like, we were joking, man, it's like, it's all coming right back around, like the same things that we were all worried about back then are…it's just a rehash of all that again, so I’m trying to gear up for that as well. That's a very valid concern.

Tom: It is a mystifying trip, but yeah, I do…let's just say I wish there were better choices, you know?

Andrew: Yeah…well, I think that's a good way to end it here. Thank you so much, Tom, for taking the time to speak.

Tom: Yeah man, total pleasure. Really good to catch up. I know your life's in a fairly busy place too, but I hope everything goes smoothly from here.

Andrew: Yeah, it's good to connect with you, though, and hear a little more about the work you do and how you do it, and what the thoughts are behind it, so I really appreciate the insight.