I’m pleased to introduce a “Sound Methods” podcast, aimed at interviewing artists about their processes and inspirations. It was an easy choice to ask Marcus Fischer to kick it off.

What follows below are my thoughts and impressions of his work, as well as a full transcript further down which has been lightly edited for clarity and filled with all kinds of embedded links and images to add context to our discussion. [Content warning: some of our discussion includes mention of gun violence in the context of Marcus’s latest exhibition at Oregon Contemporary.]

Marcus has been one of my absolute favorite artists working in ambient/experimental music for quite some time now, and has significantly influenced and shaped my own musical process: literally, by introducing me to the Octatrack and eurorack systems, and more generally, by producing some of the most beautiful music in the genre, full stop…it’s timeless stuff that I revisit all the time for endless inspiration.

After many years as just a fan, I feel lucky to call him a friend now. We’ve spent many hours in tour vans together and shared stages across the western US, Iceland, and the UK since 2018. I have so many fond memories from our shows together, and I still look back on them as my favorite touring experiences.

His music is hard to describe. It would be a gross oversimplification to use words like “tape loops” or “ambient guitar,” but for the uninitiated, they do offer a starting point.

More specifically, and in my opinion, the central theme of his live performance is a kind of “call-and-response” interplay between

his immediate actions with processed guitar and samples, and

their echoes, which run through his Nagra tape recorder.

To see it in action is as much a visual experience as a sonic one. You’re instantly made aware of the lengths of magnetic tape he strings about the room. They’re arranged according to the geometry and orientation of a given space, and Marcus talks about this as a way to establish a “timescale” to work from for the subsequent manipulation and re-pitching of the loops. The tape is an active recording buffer in plain sight; it’s taking in the performance, playing it back, and establishing a presence on stage at all times.

The addition of field recordings, tuning forks, handmade instruments, eurorack synthesizers, and other electronics on top of all this creates a truly unique blend of fragile, restrained sound that practically begs the listener to lean in a little closer and absorb all the details. Each new layer of sound is carefully looped, sculpted, and built up over the length of a set without interruption. No two performances are exactly the same, and each one is lost to memory when the set ends. His whole process is very transparent, and it’s mesmerizing to witness.

He’s a tremendously talented solo musician, but what strikes me most about Marcus is the sheer amount of versatility on display when you examine his artistic resume. There’s a lot to explore there: photography, visual art, art direction/styling, sound art installations, etc…not to mention all of the collaborative recordings with the likes of Wild Card, Taylor Deupree, Simon Scott, and so many others. It makes an interview like this really hard, because there’s so much to unpack across many different mediums!

I interviewed Marcus over videoconference at his home in Portland, OR, on the night of Thursday, February 1. We covered a lot of ground here, including his thoughts on how he defines the music that he makes, how he approaches a studio recording vs. a live performance, his punk roots and background in music, and the ideas behind his profoundly moving exhibition on display as of this writing, called “Mass.”

For more information about Marcus’s work, including photography and video of the installation pieces that we discussed in this interview, please visit his website at mapmap.ch.

Transcript

Sound Methods 001 - Marcus Fischer

Andrew: Hi there, and welcome to the Sound Methods podcast. My name is Andrew Tasselmyer and I'm a musician based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In this interview series, I'll be speaking with a variety of artists in order to probe their creative process and motivations. I'm hoping to shed some light on their practice and give you some valuable insight into the work that they do.

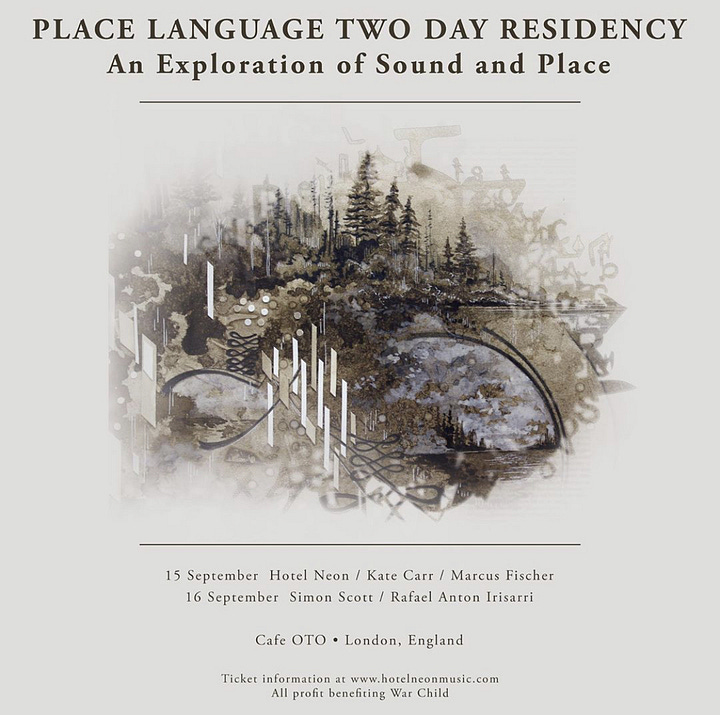

In this first edition of the show, I'm honored to be speaking with my good friend, Marcus Fischer. I've been a fan of his music and visual art for a long time now, and in recent years, I've been fortunate to grow closer to him after we toured together in the U. S. and Europe.

Marcus is an interdisciplinary artist and musician based in Portland, Oregon. He is a first generation American artist who creates, collects, and transforms sound into immersive, layered compositions that accompany performances and exhibitions. His site specific assemblies of exposed speakers, tape loops, and objects are characteristic of his installations, paired with melodies of restraint and tension.

He has released numerous recordings, both solo and collaborative, on 12k, and has also contributed two soundworks and two performances to the 2019 Whitney Biennial as the sole artist from the Pacific Northwest included in the edition. Marcus has been awarded residencies at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art. Marcus has performed and recorded as a solo artist, as a member of Wild Card, and in collaborations with artists such as Taylor Deupree, Aki Onda, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Laura Ortman, Stephen Vitiello, Calexico, Raven Chacon, and Simon Scott.

Without further ado, here's my interview with Marcus Fischer.

Andrew: Alright Marcus, thanks for joining me here. I have a lot of questions that I want to ask you, but I think I'm going to start with one that made me laugh as I was thinking about it a little bit. I wanted to ask you about the “minimal grunge” tag that I always see on your music online.

I think I've seen it on SoundCloud and Bandcamp a few times, but you've tagged it as “minimal grunge” in style. And then I know you've got those stickers with the quote-unquote “ambient” word on there, and so I'm just kind of wondering: if you were to think about it and explain it yourself, how you would define the music that you make? Do you even care about labels? Is there something that you're intentionally trying to go for, or how do you define?

Marcus: Yeah, I think that the music that I make, although it might follow a certain continuum, I think that it changes depending on the project. So, I don't know…the minimal grunge thing was like, I just started thinking about genres and subgenres that have a…I mean, I guess it's kind of like a nickname, you know, like you don't choose your nickname - people nickname you, and then that's how it happens.

[Music journalists] are the ones that invent genre names, not the people that are actually making it. And I really don't think it's important for the people creating something to be the ones to define it. I think that you put art out in the world and then it means different things to different people, or people feel the need to put it in a box and label it so that it's easier to package, or it's like shorthand for something, but my idea with the minimal grunge thing was that, apart from it making me laugh, it's primarily guitar-based music from the Northwest, but it doesn't fit… it's not rock music. It was just kind of funny because I was just thinking about regional music. And so if I was to pick a regional Pacific Northwest genre, I'd be hard pressed to find something better than grunge for that…and then, it being minimal, that's kind of that.

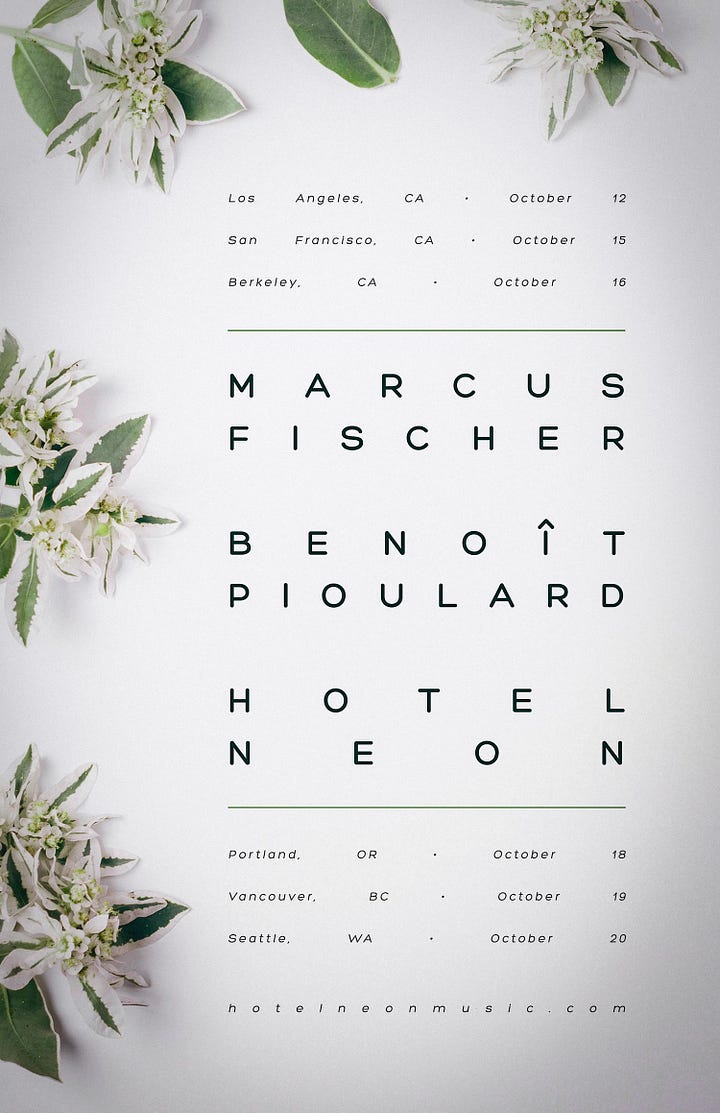

The “ambient” thing was funny because that was like, when we did the Hotel Neon (and me) euro tour, that's when I made those stickers because I wanted merch to sell, but I was like, “I'll make stickers.” But then I'm like, “I don't want to make stickers with my name on it.” That seemed like a really bad idea.

So, I had been thinking about that “ambient,” you know, “ambient” in finger quotes kind of thing, and how it really doesn't mean anything and people call things ambient that I really don't feel like fit in that label. But then who am I to decide, too? But yeah, Virgil Abloh, the now-deceased creator and art director for Off White, had that graphic identity where he put the straight quotes with block Helvetica text.

And so, if I was gonna find something that had quotes to riff off of, that was the best possible thing I could think of, so that's that. But I've been shocked at how those stickers just keep going, like people keep..I mean, yeah, I'm sure in no small part due to your representing the quote ambient label.

Andrew: I was going to say, they've traveled remarkably well. They've reached kind of cult status at this point. I see them all over the place. I've seen them copied, I've seen them ripped off. But it really struck a chord for whatever reason. I think you're so right though; it is really funny how [ambient] has become like this catch-all term for anything that's just generally instrumental and vaguely atmospheric. It doesn't really have a defined meaning anymore. And so I think that there's actually a very deep meaning to that sticker. Every time I look at it, it's kind of funny, like, “what even is this?” I don't know.

And you bring up the tour that we did together. I'm glad you did, because that actually leads perfectly into my next question. I was going to ask you about your performance. I've seen you play many times, it’s always amazing. We've done two tours together now, and I've seen you adapt your set in pretty drastic ways based on the surroundings, wherever we're playing.

I'm thinking of the time we played at Disjecta over there in Portland, and you had strung the tape loop up across the rafters there. And then we played on that now infamous stage in Berkeley, and there was a piano sitting on stage and you got up and played the piano at the end of the show.

And so…and even, you know, I'm thinking too about that performance that you did for the Whitney Biennial in that atrium space. You had your gear kind of lined up in a circular arrangement around you, and I'm wondering how do the surroundings that you play in impact your state of mind and the performance? What decisions you make? Does the context of the room and the audience dictate some of the choices that you make, or are you not really thinking about that in the moment?

Marcus: Those are all really good examples. Yeah, it very much does depend on the architecture of the space, what kind of sound system it is, like where the audience is going to be viewing. And yeah, I mean, I'm sure that you've seen me play probably close to a dozen times or something, but if I think if you were to put those performances side by side, I think there'd be a kind of language that would develop, that things are referenced throughout different performances, but I would think that no two would be exactly the same either in structure or in sound. I mean, maybe the same palette of sounds or the same set of tools, but yeah, I very much take into consideration the space.

I think that, especially the ones where I'm using tape loops and engaging the architecture of the space, whether it's ceiling height or length of floor or anything, because of the way that I use the tape, I'm using it like a memory system, so I can take bits of what I'm doing and dump it to the tape.

And so then, the length of the tape, the height of the ceiling or whatever, kind of becomes the baseline of the time scale that I'm working in, so how long it takes for something to come back around. And so, yeah, I don't know..it’s a matter of thinking about different ways of defining time, and I think that somebody that might work with beat-based music might think of the tempo and length of bars or whatever, but I kind of wind up thinking about it in terms of how long it takes for that loop to come back around.

And then I can speed it up by doubling it or slow it down by halving it. And so I'm working in divisions of that [baseline]. So a lot of times I start with the tape recording at the fastest speed and I can drop it down, then halve the length. And now I've doubled the the duration and dropped everything by an octave.

And then as I build up more layers, I can do that again. So it's just a matter of adjusting to that specific timescale.

I think that the other part of the performance that I enjoy is very much making it a transparent process. So I start with nothing and then people get to see the way that it's built up, using things that I brought with me or things that I found and then making the layers kind of evident as far as what sound is creating what, and then how it builds and then how you can subtract it and then the way that I interact with the tape changing the sound too.So, it's like this interesting additive process that's, in a lot of ways, the antithesis of my recorded material, and I think I do enjoy keeping those two disciplines separate because they do feel like two totally different skill sets to me.

Andrew: So, you’ve completely read my mind; we’re on the exact same wavelength because, literally, the next question that I wanted to ask you was, “does that differ?” I just brought up all these examples of your stage performances and adapting to a venue, per se, but I was gonna ask you, “how does that differ on stage versus the studio?” Or, you know, I know you've worked at a couple of different residencies now; you've done the Rauschenberg residency, you've done a couple other ones like at the Bemis Center, for instance. I mean, when you walk into a setting like that, I wonder, do you go into those kinds of settings with a plan, or does the setting that you're walking into - in a studio or a residency - shape what you're doing versus the stage?

Marcus: Yeah, it does. I mean, I think that when you're thinking about a residency, or some example where I've been given the time and space to work on something, I usually have a project, maybe two projects, that I would…in my mind, are things that I would like to accomplish while I'm there, but totally leaving it open to what else is going to happen in this space, because I think [I know] myself and I don't like to just beat my head against the wall if something's not working. I think because I have these different disciplines and other things that I can jump in between, it sort of winds up being a nice way to keep momentum going without just forcing myself to finish one specific project.

So, yeah, I might work on recording music for a while. But if I'm getting tired of it or I'm not getting anywhere, then I can go work on visual art or do something else. I think that…usually with an album, or something like that, there’s a “project" and I already have a concept in mind. And then it’s having some kind of guiding idea, and then working towards that and taking steps to reevaluate whether it's still on that trajectory, or if something else is changing. And then being open to those changes while also trying to honor the original concept.

The album “Loss” I worked on at the Rauschenberg Residency, and that had a very specific concept in mind, but a lot of the tracks that didn't fit with that wound up as tracks on “Lowlands,” the album that I did with Taylor, which is the only one that we've done remotely. And so it was kind of nice because I could jump between those two projects and keep going.

So I had my solo one, which was very hyper specific in what I wanted to include or what I wanted to exclude, I guess, at that point. And then I could reuse some of the building blocks that didn't quite fit with Lowlands. So to me they're almost like sister records because they were done at the same time, but have different voices.

Andrew: Oh, that's awesome, I had no idea. I love that. I love both of those albums. Probably my two favorite in your whole catalog, to be honest with you. That's really interesting to make the connection.

Marcus: Yeah, I think there's one guitar sample that is on both records by accident. And it was like, I realized it only after, like, way after the fact, and I don't even know that anyone else would notice it, but I was like, oh shit…

Andrew: Oh jeez, I'm going to listen really closely now.

Marcus: Yeah, it's an Easter egg. But yeah, I think that, like, as far as performance versus recorded material, I think that the performance is something that's very specific to that moment in time, and it only really is gonna exist in that time.

And then with an album, I wind up maybe like…maybe it would start in a similar process as far as the additive building, but then the compositions really take place in the editing phase. So, a lot of it is just doing these long form improvisations and just cutting, cutting, cutting, cutting, cutting everything down until it's just very specific to what I want to be included in there.

So yeah, I dunno, they're like totally different to me. And I think that I enjoy both a lot. But I'm just way slower with finishing solo projects than collaborations also because of that…when I'm left to my own devices, if I don't have a hardcore deadline, it's just hard to get motivated.

Andrew: Yeah. And so you brought up Lowlands with Taylor and then you just mentioned the collaborative work that you do, too, and so I want to dig into that a little bit. I know you've been pretty active with collaborations recently, you had that new Low Flying Owls record that you did. I've seen you playing and recording a lot with Wild Card recently, too. And then obviously you've done plenty of stuff with Taylor and with Simon Scott and a bunch of other folks, but I'm wondering: do you approach a project like that differently when you know you're going to have a collaborator in the room?

Or do you find that you have inclinations or tendencies that still come through in a setting like that? How much does working with a collaborator alter your approach or affect your process?

Marcus: Working with a collaborator is really freeing for me in a lot of ways, because I think as a solo artist or solo improviser, it's like there's no one to blame but yourself, if that makes sense.

Andrew: It absolutely does. Yeah.

Marcus: So then when you have somebody else to play off of, it's kind of a lightening of the load in a way, because then I can have something to respond to. I think part of the reason why I wind up with these extended tape things is because I'm kind of doing it like I’m collaborating with myself, or improvising with myself from a different period of time…it gives me something to respond to, I guess is the short answer, but with a collaboration, I haven't done that many remote collaborations, actually. Most of them have been in person, like the album I did with Simon and all of the ones with Taylor except for Lowlands, have been in person.

But there's something about the remote ones that are a kind of different thing, especially if you're not the one initiating it. I think that the Low Flying Owls one is a good example. I came into it after almost everybody had already played their parts. And so I listened to the raw mixes and I was like, “I don't know. There's not space for me here. I don't know what to do in this space.” And so that's why I wound up playing drums and vibraphone and bass on that, because it was already a well-structured, beautiful, drifty kind of record, which I think was expected from the kind of Between collaboration history, as far as 12k stuff goes. And so, I kind of threw a monkey wrench into the whole thing by playing drums…I don't think, or I don't remember if I told Taylor and Stephen that that's what I was gonna do, I think I just sent the recordings to them, and they're just like, “oh, now we have to rethink this whole thing, like all this.” So it was kind of funny, but I really like it, I think that it turned out great, but yeah, trying to play along with five other people who are all kind of doing their own thing was definitely a challenging thing. But yeah, I like it.

I don't know, it was like…I know the other thing that's nice about collaboration, especially in a live setting, is you don't need to play all the time. That's like the…like with Wildcard, that's one thing that I love is you know, “here's something that Bill is doing or that Paul's doing. And it's so good.” And then I'm just like, “okay, I just want to listen to that for a while,” you know? So I fade out what I'm doing. And then maybe after I absorb it for a while, I can think of something that I would want to contribute or play off of or something, but when you're not the sole person responsible for making all the sound, it's really liberating.

Andrew: I totally get it, as someone who plays in a trio most of the time. And I have a number of duo collaborations that I do. I thrive off that energy. So yeah, I was very curious to hear your perspective on that. And especially on the Low Flying Owls record, yeah, the drums…that was such a cool touch and a very unexpected thing. Like you said, given the personnel, given the label, you come in with a lot of expectations there. And so that was, I think, a really beautiful curve ball for everybody to hear. And I really liked that.

And correct me if I'm wrong, but you have a history as a drummer, right? I think I remember talking with you about this at one point, but you grew up playing drums if I remember correctly.

Marcus: Yeah. When I first started playing music as a teenager, I played with two friends and that was like I jumped straight into playing music, without taking lessons or doing anything. It was about making music with people, making it in the same space with people and making sound. And we all switched instruments between guitar, bass, and drums, and it was a great way to learn. I think it's hindered me in a lot of ways, but it's also made me not hesitate about picking up a instrument that I don't know how to play.

But yeah, so then I did that for a lot of years and then when I moved to Olympia, Washington in college I brought my drums with me. And then because it's always hard to find people to play drums, and I had a house with a basement, all of a sudden I was playing in like five different bands. It was fun. It was great. I played in a mostly instrumental math-rocky band, which really challenged my abilities to think about rhythm and time scale and everything. We had played really long songs with lots of different time changes and weird things happening.

And then I played in hardcore bands and one kind of, like, almost like a noisy new wave band, different things. It was all kind of...yeah, all different styles and it was great, and I got to be really good. Or at least, what I thought was good at the time. I would still play shows and be like, “oh I'm the worst drummer at the show,” you know, and that was always kind of a bad feeling, but at the same time, I was like, “okay, I can be better.”

After moving to Portland I moved into an apartment, and then I just didn't have space to play drums anymore, and so then I kind of…that's when I switched to doing more quieter, “headphone” kind of music. I was always doing four track stuff forever, but yeah, I took like a ten year break from playing drums.

I played a little bit of drums in Unrecognizable Now, which was the duo that I have with my friend Matt Jones, and we switched between…I played baritone guitar and we did laptop stuff, and then he played guitar and keyboards and then I would get on the drums now and then, and Ted Laderas played with us quite a bit doing cello and stuff. So it was kind of an ensemble, even though it was just the two of us in the middle, but yeah. I still have my drums, they're set up right now, but I just don't play nearly as much as I would like to.

Andrew: That’s how I feel with bass these days. I grew up a bass player…I'm glad you brought up those experiences. I think that those are all really valuable. I think I look back on a lot of that stuff that I - the bands I played in in high school - and I was so far out of my depth and way out of my league in terms of the skill level of the guys I was playing with. I mean, they were playing circles around me, but I think you mentioned it earlier that it really taught me, more than anything, to not be scared of picking up an instrument, even if I don't feel like I'm personally that competent on it. I do think there's a lot to be said for the lessons that are learned when you're face to face with other people in the same room playing music together. Those were hugely valuable for me and definitely set the tone for how I prefer to work, in terms of collaborating with people rather than totally being in my head all the time with solo stuff. So I totally resonate with those stories there.

Marcus: Yeah. And I mean, I think that playing with other people, especially if they're out of your league skill wise, you can just listen and there's no shame in being minimal or whatever…I just went and saw Codeine on that last reunion tour, and I was standing on Stephen's side and just watching him play bass, and I'm like, “Oh my God, it's so restrained and so simple, but it's so good.” There's nothing that's virtuosic about it. The restraint is what's virtuosic, you know, and so, yeah, I'm a big fan of that. I mean, like Mo Tucker's drumming or anything, you know…there's something to be said about the person that can just hold it down. They might not be the flashiest, but it's like, if they can just be solid and hold it down, that's great, you know? It's an important role to learn.

Andrew: Yeah, you learn to listen and leave space for other people that way, too.

Marcus: Completely, yeah.

Andrew: Yeah, it changes a lot of things when you figure that out.

So I'd be remiss if I..in a Marcus Fisher interview, I've got to ask about tape looping at some point in more specificity. I'm curious about…I was trying to think of how to ask this question exactly. But I think you've been synonymous with the Nagra tape loops for a long time. I think you were doing that before it was cool on Instagram, and back when the machines didn't cost, you know, $10,000 or whatever the hell they're going for now on Reverb. I don't even know. But I'm wondering, do you still think of the tape as the backbone of what you do?

I know you were talking about it earlier, you can walk into a room and think of “timescale” when you look at a loop taking up space. That's a little different than I've heard other people describe it. Most people refer back to the nostalgic sound of a tape and the warble and all that, but to think of it in a more physical sense, as a timescale, to me is really interesting and really fascinating.

Would you still say that that's kind of your primary focus musically, is on the tape loop as a manipulated timescale? Or are there other pieces of equipment, other kinds of gear that you're getting into these days that are starting to have more of an influence on what you do?

Marcus: Yeah. That's a good question. I guess the tape thing, it's…for me, that's like, before I could even play an instrument, I was using tape recorders. That was sort of my intro into the sound world. My dad had a bunch of tape recorders as a kid and I got into taping stuff off the radio and making collages. There might be a song and then it'd be some stuff off the radio, you know, like just random kinds of things, and so I really got into that as a way of making and reproducing sound.

And so for me, it still is that - it's a tool. But because it's one of the things that I've used the longest, it feels comfortable and still surprising. I can know, for the most part, what's going to come out of it. But I…especially when you're dealing with loops and dropping things in as far as overdubbing or erasing and everything, it can still be surprising and it kind of forces you to make choices that you know…there's not “undo.”

And so it's like you're making a choice, and you have to accept that choice and continue with it. Like, yeah, the fact that I can hit a really off note on a two-minute loop and then have to wait for it to come back around and really make the choices… “have I changed? Have I slowly decided to change the key of what I'm playing in based on that one note?” That's like, those are real choices that have to be made and in a live situation, I have to accept it. I know it's coming back around based on…I usually use a piece of colored tape for the splice, so I can always see where it's coming and keep my eye on it. [So I think] there's consequences to these actions.

But yeah, as far as the sound of it, specifically, I do like the sound, and I like that it can be…it can take signal at vastly different levels and have it come out all right. If you saturate it, it sounds great. If it's quiet, it sounds great. And then especially if you're doing sound on sound, it's a more dynamic way of overdubbing, in a way. You can hit it really hard in some specific frequency and it'll persist generation after generation after generation, where it's something else you might play like in a lower register that will just be gone the next time it comes around, like it can't overpower the record head as it comes back around so it's just like…there's things about it that are surprising in that way.

As far as other things that catch my eye, I think that I jump back and forth between different things. And there's a lot of things that like I wind up doing stuff with that never winds up in a performance or on a recording, but it's something that's just a way for me to escape for a little while.

I think the Buchla Easel Command thing is…that's something that I've had for a couple of years now, and I've been so on the fence a bunch of times about whether I should sell it or not. Cause like, I've never really…I don't know, it still is challenging me in a way, and I think I kind of like it for that, but at the same time, I'm not sure if if it fits in my workflow, shall we say, or my sonic palette or anything. But I don't know.

On the Substack thing, I posted that little clip at the end of my last entry that was just some Buchla thing, and I think that that might be the first time I've shared anything that I've done with it.

Andrew: Yeah, and that's kind of why I asked the question. I saw that post and it instantly came to mind, because I always think of you as, you know, “guitar and tape.” And modular stuff is in there too, obviously, and you work a lot with field recordings and things like that, but I don't know if that…if anything in the last couple of years, I know I personally have kind of gone deeper and deeper into the Octatrack stuff and that has totally shaped the way I'm doing things now. So I was curious, yeah, if the Buchla is here to stay, or if we might see that come up on other things in the future.

Marcus: Yeah. I don't know. I was having this conversation with a friend a while ago about how taste is like a prison. Like, you know you've got a certain aesthetic or something, and then you're just, like, stuck. It's just like, why does one thing make it and another one doesn't? Or you've just immediately cut yourself off from some certain amount of possibilities. So I kind of feel like, for me, some of it has to do with that. I’ve just imprisoned myself by deciding that none of those sounds fit what I want to do, and it's just like, I've done great things with it in Wild Card and I feel like it fits better right there than in my solo stuff.

And like, and maybe that's just a stupid way of thinking, you know? I'm not doing anything else, so I might as well share more of that stuff. I don't know. Yeah, there's certain things like that I've gone through, or I'm like, “okay, I'm doing the same thing on these 10 different tools and kind of just like figuring out how to do it, and maybe it's better to just get out of that altogether…”

Like what I do with the Octatrack is the same exact thing that I do with the ER 301, which is the same thing that I was doing… It's all just like, I find these workflows where I'm like, “Oh yeah, can I record this, but then manipulate it in these three different ways?” And then it's just a funny way of doing things rather than taking each thing as an instrument unto itself and working on it.

Andrew: I was kind of laughing to myself; a very similar thought crossed my mind the other day. I've been playing around a lot with software from a company called Slate and Ash that produces these really beautiful Kontakt libraries, and they came out with a new one recently. And it's very much built around…not totally atonal, but very “harsh,” I guess, for lack of a better term, samples. Things that I'm not used to working with. And so, I caught myself the other night. I was sitting there, you know, playing around with it for a couple of hours and here I am trying to work this beast of an instrument into my typical, soft, kind of gentle droney stuff that I do.

And I'm like, “what am I doing here?” I'm trying to force this thing to fit, like you said, the prison of my personal taste. And I just, I had to laugh out loud as I was doing it because I'm like, “man, I'm just never gonna get outta this hole.” I've built this castle for myself that I'm never gonna be able to leave. But I'm trying. I'm trying to push the boundaries.

Marcus: I think that’s good. I mean, the first step is recognizing that, I guess. You're just like, “Oh yeah, this is the same kind of thing or whatever.” I don't know. It's like, it is interesting when you realize that you're just in this…you've put yourself in a box in a weird way, and it doesn't feel great.

Andrew: No, it doesn't.

Marcus: But yeah, I don't know. I struggle with that stuff. I've done a lot of different things over the years, and then I found a tape that I had recorded in the 1990s that was all on 4-track using very similar production techniques to now, and I was like, “oh my god, this sounds like I could have done this a year ago or whatever,” and in some ways, I was like…”oh, okay, I feel kind of justified that, the tastes of the world came around to my side.” But at the same time, I was like, “oh, I've made very little growth in my solo work over the years.”

Andrew: It's dangerous for me to think about it too long. I start to doubt myself. Yeah, I mean I think there is…I think there is a lot of value, though, and a lot of importance in figuring out who you are. You can try to fight yourself for ages, trying to bend yourself into a corner that you just…you're just not going to fit. And, you know, I think it's worth recognizing what your strengths are, to put a positive spin on it.

Marcus: Yeah, I agree. I mean, it's like you put your 10,000 hours into making minimal grunge or whatever, and you're gonna be there.

I think that it's…recognizing those things and acknowledging it, and then choosing where you go from there, is kind of interesting. But yeah, I mean other things…like I did that whole really long album last year that was basically all MPC 1000. And that was definitely me trying to…although, like, sound-wise, it probably sounds very similar to the outside listener to everything else that I've done, to me, the process was so different. And then also putting up these guidelines as to what the working method was, and then the duration and all those things. So every track was just going to be 12 minutes. And I was gonna do no overdubbing or editing other than chopping the ends off, you know? It was going to be what it's going to be, and a “single instrument” kind of situation.

And that was…yeah, it felt good. Taylor [Deupree] wrote the other day and said that he's still been listening to it every night or whatever this week.

Andrew: So, it's so funny, because again, you've read my mind. After the previous question I asked, my next bullet point on my little list here was “ask about dodecalogues.”

I wanted to ask you about that, because I also love the album. I thought it was really beautiful. I love the concept: twelve 12-minute pieces with one instrument. It was all MPC, right? Just a single instrument?

Marcus: Yeah. I mean, it was all played on the MPC, but the samples came from like, you know…it was basically OP-1 and MPC, or a guitar and MPC kind of thing, but it was all played by hand on the MPC, so not sequencing anything because you know that I'm really bad at sequencing…so yeah, but it was like using those 16 pads to play samples. The way that it's set up, you can have loops, you can have one-shots and all that stuff, and all mapped to the different pads, or like different gate modes and note repeats and different stuff. But yeah, it was just like sitting there with the MPC in my lap, and then just playing for 12 minutes.

Andrew: That’s exactly how I pictured it in my head, because I know you had mentioned to me before…we've talked about Octatrack stuff for, you know, a long time, and [it’s] always cracked me up how you never hit “play” on it, which is mind blowing to me. But to know that Dodecalogues, specifically, that was played manually, I think it did add something to the way that I heard it. It kind of added a little bit of context in terms of thinking about something like a sampler being a very active and engaging instrument that you can play and that you can work with. I think it added a lot to that album for me, personally, knowing that it was not sequenced material, that it was manually manipulated over time. Just wanted to mention that because I think it's a really impressive work in that context.

Marcus: Thank you. Yeah. I feel like you could like there was a lot of things that I could do when taking that approach that I wouldn't have been able to do with sequencing in real time, because you're locked into, like I was saying, number of bars or whatever.

And like that, I could use the sliders to address the loop length of different samples simultaneously, so you can change the A and B point, like the “loop in” and “loop out” of a sample on these two faders that are on the side, but then…so if you put like five different samples in there, and they all have different lengths, and then you're operating that on all five that you're holding down at the same time, those have radically different timescales over the throw of the fader. So if you have a four second sample or something like that, you've got all kinds of weird granularity in there. And then if you have a minute long sample, that’s way coarser.

So it was really interesting to play with it, keeping that in mind: like I know that this pad is going to be a really short loop now, because I have condensed it down, but then I did that in order to find the sweet spot of this other one. So it was really interesting using that as a hand-played instrument like that. And then with aftertouch, and you have like filters and LFOs on everything, so it's like…it's a really expressive instrument.

Andrew: Yeah. It made me think about the MPC instrument myself. Because I've tried - well, I haven't tried a 1000 before, but I've tried a couple of the later ones like the Live and the the other ones to come after that, but I've never gotten along with that interface very well. It made me want to give it another shot, to be honest with you.

Marcus: Yeah. I mean the One and the Live or whatever, like I just…I had a One and I was frustrated that it didn't do…I was like, “Oh, it'll probably do all the things that the 1000 does plus all this other stuff.” And it didn't. I couldn't have a one shot and a loop on the same grid of pads like you can with the [1000]. You’re like, “Oh, this [bank] is a drum program. This [bank] is a whatever.” And then as far as the interface goes, I was like, “I might as well just be using [Ableton] Live for this stuff.” It was just…it got too…it was frustrating. And then it was just trying to be too many things.

I think that the 1000 is pretty amazing because they're pretty cheap if you find one. I think I found mine for under $300, and then you can fix them with parts that you can buy online. Mine needed some buttons to be replaced, and that cost me like $20 or something. And then I upgraded the pads, and then I did this, and did that. It is a user serviceable instrument, which is…just doesn't, it's not a thing anymore.

Andrew: It drives me nuts. Yeah. Especially cause I'm deep in the Apple ecosystem at this point, and I still have fond memories of when you were able to open it up and add more RAM and update the drive, replace the battery. So that kind of stuff feels like such a luxury now when it's available.

Marcus: Yeah, you could make choices after the fact, rather than sinking all your money into something when you first bought it.

Andrew: And are we right to assume that there will be more volumes of that [Dodecalogues] series? I'm very optimistic because you titled it “volume one.” I’ve gotta ask the question.

Marcus: Yeah, I have…I probably could compile a second one from other stuff that I recorded last year. But I listened to some of that and I was like, I thought that it sounded too similar to the last one. So I'm thinking this year I'm going to pick a different kind of methodology. Similar framework, but maybe a different…pick a different instrument or do something.

So yeah, maybe I should do something with the Buchla to justify its existence in my crowded studio.

Andrew: Well, I next wanted to ask you about some of the installation work that you do, because I think it's, to me, a really impressive body of work that you've built as a solo artist, as a collaborator with the residencies that you've done, and also the installations that you've set up. I know you have one ongoing now at Oregon Contemporary, if I'm not mistaken.

Marcus: Which was Disjecta.

Andrew: Disjecta! Yeah. Okay. I was going to ask. Yeah, I was going to say, I recognize that address.

But it's a really profound work. I mean, I'm wondering if you can kind of talk through that a little bit, just for those who aren't familiar with it. You're essentially…to sum it up way too short and way too simply, you've taken gun violence data and created a graphic score out of that. So can you explain a little bit about how you were thinking through that?

Marcus: Yeah, totally. In 2022 I was getting ready to do the Bemis Center Sound Art and Experimental Music Residency, and coming [there], I had a couple of projects in mind that I wanted to work on while I was there, but then there just kept being more and more shootings and things that I was struggling with, just being inundated with this news, and I started really looking into the information, being curious about how much it was growing. These incidents are increasing in frequency.

I first started looking at gun violence in general, and so, looking at how after the assault weapons ban was lifted, how, there was this exponential rise, especially in shootings using the the AR-15, and that was…it kind of then sent me down this other path of looking at mass shootings. I originally was going to do a project about gun violence, but it's insane to say that the amount of data that was there on shootings in the United States was simply too overwhelming for me to do anything with that data. It would have taken me years to do it. And so, the shitty compromise was just looking at mass shootings.

Mass shootings are considered an incident where four or more people are killed or injured, and not in the perpetration of a crime. So, it's not like somebody robs a bank and like four people get injured or whatever; that's not on the list. These are just these kinds of random occurrences that happen in this country and literally nowhere else.

And so I took… I was going to go from the point where the assault weapons ban was lifted till present day, and that was too overwhelming, too. I started by making these charts, and I kept having it… you set the ceiling and the floor to make graphs, and the graph was - I was going month by month - I kept having to raise the ceiling. And so, you know, then it kind of diminished the…when the chart was getting really tiny at the point where there was like five people being killed or six people or 10 people because you had an incident like the one in Las Vegas where it was an insane amount, it was diminishing these other losses of life. So yeah, it was all a really dark rabbit hole to go down.

But yeah, I made these graphs based on data for the year 2022’s mass shootings in the US. And from that, I used the charts as a graphic score to make 12 pieces of music for this installation that I did.

The first 10 months of it I showed at Bemis in the fall of 2022, and then the last two I completed for the current exhibition. And so it's a piece called Mass, and it's like an arc of 12 speakers sitting on these concrete pilings, and in each speaker there's like a handful of spent bullet casings.

And so depending on how active that particular month was - each four minute movement represents a month - so, depending on the number of people killed or injured across the month’s worth of information cut down to four minutes, there's more or less activity as far as rattling these spent bullet casings.

It’s a 14 channel installation. There's 12 of these speakers with the bullet casings and there's a subwoofer. And then there's a speaker with the voice of this artist Senga Nengudi, who's a friend of mine, who is an amazing woman. She’s like the same age as my mom, in her 80s, and she was one of these…the artist that was featured in this exhibition at the Brooklyn Art Museum that was called Radical Black Women of the 70s. And she was a sculptor and performance artist in LA in the 70s and did some really amazing work. But I love her voice. Her voice was on the that Words of Concern piece. That's the piece at the Whitney Museum, purchased for the biennial.

And so, yeah, so then she reads the name of each month, and then it enters into this piece of music that engages the speakers to rattle the bullet casings, and it winds up being this kind of…it's a pretty visceral experience; it's not supposed to mimic what it would be like to be in a mass shooting, there's no sounds that sound like gunshots or anything. It's all just sine waves and white noise.

And so, whereas most of the music that I do tends to be melodic, the stuff in that is very dissonant, and it's because in order to get the speakers to rattle the the bullet casings, I needed…the thing that worked the best was clashing frequencies, one modulating another, and then you'd get more activity. Like if you're jumping on a trampoline with a friend and you get just out of sync, and one person goes launching off, it's very much that interaction. And so it wound up being dissonant, which also kind of serves the work itself. So it's kind of haunting with these low bass tones and then these other frequencies that slide up to pitch.

And, you know, I wish that it came across better in video just because so much of it is being…like your whole body being affected by the low frequency, and then seeing the whole thing.

Andrew: Thanks for describing it because I do think it is…you know, even on paper, it struck me. And I'll definitely link to some of the information and pages that are out there describing it, because I think it's really important for people to take a look at that. And really it struck me. So I was curious to hear your thoughts and your process behind it. So thanks for that. I wish I was closer and could go see it myself.

Marcus: I know. Yeah. We're in the last 10 days now of the show. Which is like, it had a good run. It’s been up since November, so it had a longer than usual time for an exhibition, and I've been really happy with the way it turned out. And then the conversations that it's led to, it's been great to have some really good talks with people about their own personal experiences. Not just with gun violence, but with loss in general - that's the theme of the show, or the title of the show is, “what was lost and what remains.” And so it's thinking about how we’re transformed by experiences in a lot of ways; it's just like, yeah, what do you choose to do with it?

I've been lucky enough to not have lost anyone in a mass shooting, but that's definitely not the case for a lot of America. I think also being first generation American, my parents are both immigrants and just thinking about how weird it is that, looking objectively at the United States as being this place where this thing happens and nobody does anything about it. It just feels really weird. They made helmet laws to protect kids, there's seatbelt laws which happen, [a] Peloton eats the family dog, and people go into an uproar about it…like, that kind of thing. There’s a lot to find objectionable about the way that…the lack of handling of gun violence in this country.

So, yeah, my way of coping with it was creating something that addressed it while trying to spark conversations about this with other people. I think that, like you had mentioned, having the outlet of music and then also then doing art, I think for me, I grew up in the DIY Punk scene of the 90s and…

Andrew: You're not going to believe me when I say this, but…

Marcus: The next question.

Andrew: You anticipated my next question nearly perfectly. That's hilarious. I was going to ask you, I know you've got a punk rock background. How does that manifest in your current practice?

Marcus: Well, yeah, I mean, I think that's like, that's it. I've had this conversation with Yann Novak before; ambient music as a platform is like…it's not an easy place to make a political statement. You know, it's maybe making an environmental statement or something that people can talk about, like their use of field recordings or this or that. But yeah, I think that for me, art and politics and music and everything is very intertwined in this way, just from the way that I came to it.

And so I think the fact that I can use sound and sound art, and my installations or other things, in order to address things that are inherently more political than my music on the surface level, has been really…it's almost like a way that I can justify it existing in this way. I don't know. It's like, I struggle with saying that any of it is worth existing, but there's…at least it's given a voice or a platform to things that I think are worthy to be discussed further in some way or another.

Andrew: I love that. Yeah. And, I think I specifically asked… these two questions are tied together to me, and I wanted to ask about them because I do think that the work you do with your installations and what you've just described here, I do think it's an important part of your resume. You know, it's easy to gloss over that stuff, but as you know, making the kind of music that we do, we don't really have, like you say, clear opportunities to make statements on things like that, things of real importance in my mind.

And I'm kind of at a point personally, I don't know if you would feel the same, but I'm getting less…I don't know, patient, with surface level art and music in general. I like to know the human that's behind it. I like to know the thoughts and the intentions behind it. And especially now, you know, with what's going on in Gaza and what's happening here with…there are all these issues that I don't know we have an option to really be silent on at this point. So I do think it is important to at least think about it. And even if [I] can't directly voice it with the music that [I] make, I do think it enters into my consciousness as an artist when I'm making stuff; I do think about topics like that. So, it's interesting. I don't do installation work and I'm not having pieces sold to the Whitney Biennial, so I think it's a really cool thing to see you get those platforms and the opportunities to surface these topics.

Marcus: Yeah. Thanks. I feel super fortunate to have had those opportunities, and it is…it's not an easy thing, and I feel like I've really been lucky to have had a platform, you know, in several high profile things that have been really, really amazing.

And the piece that was in the Whitney was made out of fear and frustration and, kind of like, “what the fuck is gonna happen?” kind of thinking, and it was a very specific snapshot in time made on the literal eve of the 2017 inauguration and You know, just kind of like a way of bonding with these other artists that I was at the Raschenberg residency with. And so we all kind of voiced our biggest fears and then I captured it on tape.

And, yeah, the most fucked up thing was really just hearing it in 2019 in that gallery space, and just being like…because at the time when it was made, I thought it was like, kind of alarmist, or maybe exaggerated or whatever. And I'm just like, “holy fuck, everything in this has come true, and more…” Yeah, I don't know. I think that that work resonated with a lot of people just because it was like, in a way, the “bingo card” of everything that could have gone wrong in a way, but it still had a really nice, “you're not alone in feeling these kind of things” message, and then also was like a checklist of the things that we need to try to defend, and if you care about these things, “keep your eye on it” kind of thing, rather than just let it go. Like, are your individual freedoms quietly going to slip away under somebody else's watch? So, I think that that's been…it was an important work for me for that, just to keep myself grounded in it all too, because I tend to go down the dark rabbit hole of things.

Andrew: I'm right there with you. Yeah.

Marcus: Absolutely. So yeah, I mean, I think that it's nice to have that outlet, and it's also interesting to, as time goes on, the people who…a lot of people that know me for music don't know about the art stuff, and vice versa. The Whitney people didn't know that I recorded and performed music when I was admitted, and when they found it out, they're like, “Oh, would you want to perform?” And I was like, “Oh yeah, I'd love to.” That opportunity just fell in my lap after being brought in for a completely different reason.

Andrew: That's so funny, but I mean, yeah, that was really an amazing performance. I'll definitely link to that and show notes or whatever here so people can watch that again.

Marcus: Yeah. That's like the probably the most perfect version of that particular thing that I was doing at that time. Yeah. And it got captured like beautifully on multi camera video and everything. It's pretty nice to have as a document of that. Because I don't think that I have many…I don't have anything similar that I could share with people.

Andrew: I'm terrible at archiving and documenting my stuff. Yeah. So yeah, that's a cool memento to come away with.

To wrap up our time here - keeping an eye on the clock - I just wanted to ask a general question about the year ahead. It's shocking that we're already through January, but there's still 11 months left here…so, what what's on the horizon for you? Even if it's not this year, even in like the next few years, I'm curious what you have your eye towards, if anything.

Marcus: I'm starting another solo record with Taylor this month. And we're gonna try to do it in a month, and we are doing it remote, so it'll be like kind of…yeah, we'll see how it goes. We have a plan, so that's good.

And yep, I'm wrapping up the art show at Oregon Contemporary.

This weekend I'm doing an artist talk with Stephanie Schneider, who's the curator of the Cooley Gallery at Reed College. So we're gonna have that talk, and then every first Saturday, I've been having different artists perform these graphic scores that I made that are in the show.

So, this month, it's gonna be John Niekrasz, who's a really amazing drummer. He's my favorite drummer in Portland. He has a duo called Methods Body that has a record out on Beacon Sound right now. And they're great. He is, he is very like textural and, and creative percussionist and drummer. So he's gonna be working with one of the scores.

Last month we had Paul Dickow and David Chandler doing a duo. They did like a live drawing, interactive thing, where they traced over one of the scores that they had printed out really huge on a table, and David wore a brain monitor thing that translated his brain activity to some Audio Mulch patch that Paul had made. It was pretty great.

And I had Christi Denton and Jamondria Harris play the month before, so it's been a great way to get people performing in an art context who I think deserve [it]. I found for myself, the way that people view things in an art context is different than they would view things or hear things in like a club or traditional music venue. For me, when I stopped playing in bars and stuff, that marked a huge shift in the way that I approached my own music. So it's been, yeah, to do that with other people is pretty awesome.

And then I've got a sound piece that's coming up in the Oregon Artist Biennial, which is happening this spring, and then another sound installation at University of Oregon, down in Eugene in May.

And then hopefully somewhere along the line, I can work on making another solo record, because it's been a lot of years since I've made like a proper one, not counting “Dodecalogues.”

Andrew: We're eagerly awaiting. I can tell you that.

Marcus: I have a lot of material, but I just…I feel like I need to start from scratch. I don't know.

I'd like to get back into performing again. Solo stuff. Since that Europe tour, I really didn't, because then not long after that was the start of the pandemic. So, I played three times or four times since the start of the pandemic and that was it.

Andrew: Yeah, I think it was our tour in Europe in September of 2019, and then in March all hell broke loose. We've only done a couple of things since then. I can tell you, it definitely feels a lot different than 2019.

Marcus: Yeah, I was so happy to be able to catch you guys in New York at Public Records. That was such an awesome coincidence.

Andrew: Yeah. We'll get you out east sometime. We can play it together. That's probably my favorite room on the entire coast.

Marcus: Yeah, I would love to play there.

Yeah, it's funny, my last show in Portland before the pandemic started was on leap day. I played with a duo with Ted Laderas at Beacon Sound. So it was February 29th. And this year is another leap year, so that's like…four years went by, it's really fucked up when you think about it.

Andrew: It’s the same Super Bowl matchup [as 2020]. It's the same presidential election candidates. It's a leap year again. All the stars are aligning…I hope it's not the case, but…

Marcus: Yeah. Monkeypox is gonna come for us.

Andrew: God, who knows. Well, it was wonderful to talk with you, Marcus. Thanks so much for making the time. I really appreciate it.

Marcus: Oh yeah, thanks for inviting me.