There’s a highway in northern Maryland, officially known as State Route 23, that’s dedicated to Gold Star Mothers. I know this stretch of asphalt well, because I drove it nearly every weekend over a 3-year span. At the time, I was living and working in Wilmington, DE while my wife (then girlfriend; soon fiancé) was working in Baltimore. Long commutes between the two cities were the norm.

A ritual began to emerge here: I’d pass the dedication sign to Maryland’s Gold Star Mothers somewhere around midnight, then immediately turn on Hammock’s “Maybe They Will Sing for Us Tomorrow,” which starts with a track of the same name. It’s a song I know by heart now: the reversed guitar loop fades in; Christine Glass Byrd’s oft-credited “angelic vocals” emerge; the simple piano arpeggio supports the pitch-shifted vocals; the slow cello panned slightly left of center adds gentle weight to the soaring guitars above… “Gold Star Mothers” is burned into my brain, and I can’t hear it without feeling my chest tighten up a little bit as my mind is transported back to that time in my life, when so much felt so uncertain during those lonely drives along northbound Route 1.

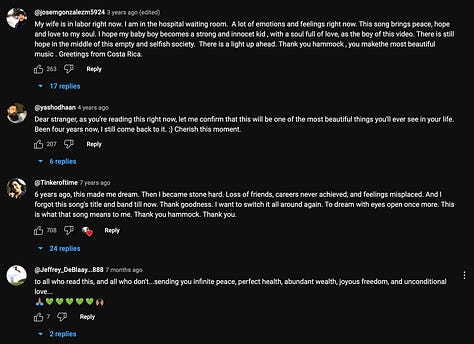

This is the kind of effect that Hammock, the Nashville-based duo of Marc Byrd and Andrew Thompson, can have on people, and the kind of effect it has had on quite literally tens of thousands of people over the years, as even a passing glance at their YouTube comment section and social media pages will tell you. Listener after listener will pour their heart out, sharing anecdotes about how and when and where they listened to Hammock during a pivotal life event, hammering home the reality that this music is emotionally charged and utterly cinematic. It has accompanied births and deaths; joy and tragedy; the lowest of lows and highest of highs.

As Marc Byrd told me, “it's beautiful and painful at the same time…I don't know a better definition of life.”

Hammock has played an enormous role in my own musical journey. I discovered them as an impressionable high school student, struggling to find a unique musical voice; when their debut album “Kenotic” was released, it blew open the doors of possibility, and I went down an ambient/post-rock rabbit hole that I’ve never really surfaced from. Needless to say, I was well and truly thrilled to have this opportunity to interview Marc.

Because the music is so loaded with emotion and humanity, I really wanted to focus my questions on understanding Marc’s broader views on the band and what motivates him. It was refreshing to hear him talk about these things, and I’m grateful for his honesty and transparency. I hope you find his perspective as inspiring as I did.

Here’s the full transcript of my interview with Marc Byrd. I spoke with him over videoconference from his home in Nashville on the evening of Thursday, February 22.

Please visit hammockmusic.com to find, stream, and purchase Hammock’s music.

Transcript

Sound Methods 005 - Marc Byrd

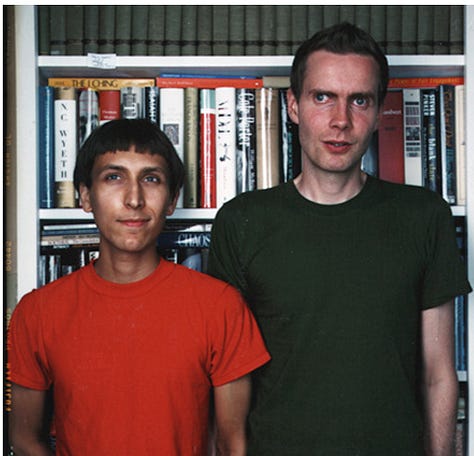

If you've spent any amount of time around ambient, post-rock, and adjacent genres in the last 20 years, it's very likely that you've heard the music of Hammock, a Nashville based duo consisting of Marc Byrd and Andrew Thompson. To describe their music is pretty difficult. The two of them have added varying degrees of instrumentation on top of their guitar playing over the years, ranging from the most minimal - just the two of them, playing hushed drones alongside cello and voice - all the way to the most maximal of arrangements, with full choirs, drums, and orchestra generating massive walls of sound.

The result is always spectacular, and it's hard to overstate the emotional impact of their songs. It's a stunning blend of beauty, sadness, and ache. The two seem to have an uncanny ability to find exactly the right way of tugging at your heart strings, probing the full range of human emotion through sound. I can personally attest to how powerfully their music can meet someone in both the peaks and valleys of life: their music has provided me comfort and inspiration for as long as I can remember, and they're a big reason why I'm making the music that I do.

I had the chance to sit down with Marc and ask him how he feels about the emotional impact that his music has on people who hear it. He reflected on this, and also opened up on a wide range of additional topics, both band-related and personal. I really hope you enjoy the conversation here, and take as much from his perspective as it offered to me.

Here's my interview with Marc Byrd of Hammock.

Andrew: Alright, Marc Byrd, welcome to Sound Methods. Thank you for being here and taking the time out. Really appreciate it.

Marc: Thanks for having me, Andrew.

Andrew: I'm trying to get my inner diehard fan out of the way, not be too embarrassing, and think of some meaningful questions to ask you. But you guys have been a band for, I think, 20 years now at this point, or close to it, so there's already been so much ground covered in past interviews and press releases and all the other documentation that surrounds your work. I'm hoping to cover some less traveled territory with my questions, and it's no small feat, but I’m looking forward to seeing wherever this conversation goes.

My first question relates back to that first point I made: you've made music for so long that's so emotional for so many people. It's very visceral and vivid, and I can only imagine the amount of feedback that you're getting from listeners on the impact that it's had on them. I'm one of those people; my twin brother, Mike, is one of those people too. We still talk about it all the time, but he wrote to you guys back in 2010 after you released “Longest Year” - that actually came out on our birthday that year, and he was telling me the other day how deeply meaningful it was to get a reply back from you guys about what your music has meant to him, and especially at that time in his life.

But I've heard people use all kinds of very intense language to describe what your music does to them, like “it changed their life,” or “it saved them” or similar sentiments like that. Do those kinds of responses affect your work in any way? I mean, do you feel any additional pressure to live up to those kinds of expectations after you hear it so often, or exceed it on the next thing that you're working on?

Marc: It's funny that you bring that up, because I just had somebody ask me some questions similar to this - he's a friend of mine - and I asked our manager, Johnny Pleasant, “is there anything that you can send me as far as correspondence?” Because I don't always look at all the correspondence, especially the Bandcamp correspondence, because it's…it’s a lot. It's a lot. And it's very intense, you know? Our comment section on YouTube almost feels like a support group. It's really amazing. I'm so surprised by it.

But what I know is I process life through music, in a lot of ways. I think [the fact that] something so deeply personal can be experienced universally is still kind of mind-boggling to me. But I also think that that says something about who we are, and how common our life experiences are.

Hammock’s not for everybody, that's for sure. But the people who get it…there's not a lot of casual listeners, I'll say that. When you're in a band as long as we have been, and they’ve lived their life with us, they have these attachments to real life experiences such that when they hear the music, they're not just hearing the music - they're reliving that life experience, and then they're probably taking stock of where they are right now in their current life experience.

So do I feel pressure? I put an immense amount of pressure on myself, to try to keep making music that…I don't know. They always say when you get older, you can just kind of phone it in, do what you want, and take it easy, and that's just not in us. There's an intensity about my connection with music and how much it has done for me in my life; it’s been the most consistent presence and companion, more than anything. When I say more than anything, I mean more than religion, more than family, more than all of it…because it has been through all of that with me.

And so the truth is that, when I think back on my memories in my life, the older I get, the things that I remember the most vividly are car rides with music - which is so strange, you know? And sometimes I won't even remember a conversation, but I'll remember the song that was playing.

I think that our music doesn’t put anybody in a different realm, like an additional realm. What it does do, I think, is it can assist us in slowing down enough to notice that which is hiding in plain sight, and experience something that's so familiar it's taken for granted, and then it becomes unfamiliar. Music really - certain types especially, and all good art can do that - it grounds you in what is, to the point that what is feels new, and strange. Anything that can make the mundane strange, to where I can see some kind of amazing aspect of just being alive, just existing…all art, I think, that's good, has that kind of element.

We hear all kinds of stuff that our music has [accompanied listeners through]…it's the last sounds people have listened to before they leave the planet; it's the first sounds some people have heard. Babies have been made, drugs have been taken, religious ceremonies have been performed. Meditation walks, sobriety, lack of sobriety…all kinds of amazing things have happened, and it means so much to people that they want to tell us about it.

Andrew: Yeah. It's really amazing…

Marc: It's astounding.

Andrew: I mean, on a much lesser scale with the stuff that I make, and that I make with my band, we still hear from people occasionally, too, and I don't take that for granted at all. It's really just startling to hear what it can do to people.

And to your earlier point about the car rides, and music that you associate with trips like that, there's music that has burned holes in my brain at this point. I think about car rides with my dad growing up, you know, driving way too fast and then listening to The Police in his old Audi A4. I remember that like it was yesterday. It's just amazing the impact it can leave on people.

Marc: And I never want to get used to it, that's the thing. Sometimes we do.

My manager is so awesome. Sometimes he will just send me [a note to say], “hey man, in case you're wondering why we do what we do, and you're wondering if all of this hair pulling and ‘what's going to go on the next album,’ ‘what's going to be the sequence,’ ‘how are we going to let some of these songs go,’ ‘this is taking too long, I thought it was done,’ and all of the pressure and all of that,” he just occasionally will send me this long email of nothing but correspondence [from fans]. And I mean, really…I am shocked, because it sounds like they're being touched by something deeper than music, but yet it's just music, right? But it's not, also…it's great.

Andrew: Yeah. Emotionally charged waves of sound.

Marc: Yeah. It's incredible.

Andrew: This was kind of the next bullet point under that question for me. It was sort of getting at the gist of what you were saying a little bit there, but the listener impressions that come in and that you see: I was going to ask if that affects the way that you hear your own work after the fact, or if you even listen to your own work.

The sense I'm getting from what you just said there is that it seems like it's heightened your appreciation for the act of making music, knowing what it can do to people. Is that an accurate assessment, would you say?

Marc: Yeah, it definitely does.

Andrew doesn't listen to hardly anything we do outside of working on it, [but] I do. I have to. I'm the one sequencing the records and coming up with…there's work late at night that I do, and so, yes, I do listen to our music. I don't like to listen to an album once it's mastered for a long time. Then I approach it so that I can hear it fresh and new, and the inner critic hopefully will dissipate some.

I hear our music, and I don't know that I can hear our music the way some people hear it, but I'm fully aware [of its effect on people]]. I mean, Andrew and I make a joke all the time, like, “man, all right, this is going to make them cry, you know?” And, you know, “this one will help on your boo boo,” you know what I mean? That kind of thing. “I hope no one's sitting next to a cliff when they're listening to this.” And so, yeah, we are aware that there's a real emotional [element]. We're fully aware, and we don't apologize for it. Starting out with Hammock, we never once said, “we're trying to reinvent the wheel, man. We're, really, really, really trying to create something brand new.” We just really wanted to make music that if we walked into a music store and it was playing, we would ask the cashier, “who is this?” That's all. That's all.

And you know, “Hammock” came from - the name, we weren't taking ourselves seriously. We didn't think anything was going to come of it. I was having a party at our house and had some friends over, and I had a hammock in the backyard where my wife and I used to lay and listen to music and look at the stars, and I was like, “we don't know what to call it. We've got this whole album done.” And my friends said, “call it Hammock.” I was like, “oh yeah, Hammock. Sure. Cool.” And I didn't think of hammock, like the lazy beach [connotation]. I thought of it more like, looking at the stars. That's what I've done mostly in hammocks.

And so, there's a contemplative element to it, but more than anything, I think it's more about, “how does it make me feel?” Because I will let go of songs that, technically, are amazing - for us, at least. I'll just say that for some people, they'd be bored. But for us, it’s like “wow, this is something new,” but if it doesn't have that…I want to come back for the feeling, right? It's more like, I'm coming back for a musical exercise, rather than I'm coming back for a musical experience. And I'm not saying that the two are separated from one another, necessarily, but if I had to choose which way I'm going to lean, I'm going to lean always on a simpler, more emotional piece of music that some people would find boring…but if you sit with it long enough, it will open up space inside of you, which all good art can do.

Andrew: Yeah, I love that. And it brings up a couple of points that I wanted to get to throughout the conversation here, but I guess I'll start with this one.

I was talking to taylor deupree the other day, and he said something that really stuck with me. I love this comment that he made, because I really resonate with it. He said, “I hate listening to the music that I make until I've forgotten how I made it.”

I totally feel that because, yeah, [when I hear something too soon] I cringe, and I hear specific decisions I made, and I start overthinking, and that's when my critic is at its fiercest: when I can still remember what went into the creation of that thing. But in the kind of music that we make, where it's instrumental, it's atmospheric, there's a good deal of processing and mixing and “after the fact” work that goes in after you've laid the initial foundation with your instrument…

I think about this all the time. People ask me, “oh, you make music, you, you play guitar - play us a song.” And like, “I can't really play you a song like that. If you give me three delay pedals, I can play you a song.” But I'm curious how you view your instrumental, musical identity. I know you play guitar, of course, but do you find yourself identifying over time with the whole product itself, like the end result [after all that processing], or do you still view yourself as a guitarist first and foremost?

I love hearing from people about that perspective that they have on what they do.

Marc: Yeah, that's a great question. I'll just tell you that when we made it in Guitar World magazine this last year, our inner 13 year olds were losing their mind. I mean like…

Andrew: The stuff of dreams.

Marc: Yeah. And not just like, a little thing online, but to be in print in both Guitar World and whatever Guitar World is over in England. I mean, that was like, even people from my hometown in El Dorado, Arkansas would understand that: “yeah, Byrd’s in Guitar World, man! Can you believe that?” You know, like that kind of thing.

So yeah, for me, I will always, in some way, be a guitarist, but I've never been a traditional guitarist. I'm never learning other people's songs. My nickname was “Marc, Marc, Marc” growing up because I used so much delay, and I've always wanted to…of course you start [playing guitar] and when you're young, you like their speed and whatever. Matt Kidd will tell you, he went through that phase too, but Matt can kind of do that stuff. I can't really do it. But when I moved into listening to more of The Smiths, The Church, The Cure, post-punk kind of things, and then Robert Fripp - I'm talking about earlier stuff, you know, really earlier stuff - and Andrew was a huge Adrian Belew fan. That's how old we are…but when I found that kind of sound, I realized that I wanted to make more of a sonic landscape than I did a really nice, performed guitar piece.

I've only had a few guitar lessons in my life. My classical guitar teacher, I only could take a few lessons from him because my studies began to completely suck; I was obsessed with it. But his words, his assessment of me, I'll say this: what he told my family was that, “he would make a good composer.” He was basically saying that, “he's an okay guitar player, but he thinks more, you know? He wants to construct.” He saw something in me. He went on to Juilliard and he was a really good musician, and insightful. He could see it at a young age; he saw something in me. “He wants to play guitar.” But in reality, [when] he told me to go home and learn some things, I [would come] in with a piece that I wrote. That's the way I've always been, and that has created some problems for me over the years.

I will say, though…I live in a town where the people who mow your yard and wait on you at restaurants can play me under the table.

Andrew: Yeah, I was gonna ask about that - living in Nashville.

Marc: I'm under no illusion of my limitations, but I am a big believer that limitations can make you have a unique perspective. It's like when Brian Eno told U2, “when bands understand their limitations, that's their identity.” And instead of it being a bad thing, that becomes their identity. We understand our limitations. We're not trying to step too far out of our comfort zone to try to prove to people…I mean, we're not Radiohead. I wish we had that, but we're not, you know?

But the truth is, do I see myself as a guitar player? Yeah, but I definitely see myself as much more of a sound sculptor. And the other thing I'll say, though, we don't just do pure ambient - we do post rock also. And I didn't even know what that was when we started. I just knew I liked Sigur Rós and Mogwai and Explosions in the Sky, and somebody said, “oh, you like post rock.” I was like, “I don't know, I guess so.” I was very much into shoegaze when the nineties hit and it was Nirvana and everybody else, and my friends were into the Sub Pop stuff. We used to joke like, “you heard Nirvana? Oh my God!” But the truth is that I was listening to Curve and Swervedriver, My Bloody Valentine, Chapterhouse, Slowdive, and The Verve's first two records. I was really big into that, and that was way more my world than the heavy stuff. I tried to do the heavy thing for a little bit, but I feel much more at home creating mood.

Andrew: Your point about limitations - I think it was Eno, also, who said even limitations in a given format or medium, the way that things are presented, that then becomes a desirable thing. I think his quote was talking about how people desire the lo-fi character, the 16 bit/12 bit CD players that had that certain character and edge to them. That's now desirable. That was a limitation back then, but it's now looked at as this aspirational aesthetic that people want to pursue. I find that so interesting.

“Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit - all of these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided.”

Marc: I mean, when I moved to Nashville, my first experience in the studio was on 24 track, two inch tape, so I learned how to create music being under restrictions. Sometimes I think that's a really good thing, especially to learn on.

But I mean, we've overdone it, you know? Like, we've really gone…our mixing [engineers], God bless ‘em, man, they have a job ahead of them. Oh God, what we did to Tim Powles between Chasing After Shadows and Departure Songs…he mixed the “B” pieces on that record, and he was like, “oh yeah, this is cool, I can do this.”

And then we did Departure Songs, and we threw that at him, and he was like, “oh my God, what have you done? How am I going to get through this?” That was just us realizing that we can play around. I also think that we can have fun doing this stuff, but I also think that we can overdo it too.

Andrew: Yeah, that's funny. And that brings up a point, too. You mentioned limitations, and how maximal you have gone at some points, but the thing that I find interesting about Hammock history…I was looking back on this because I wanted to fact check some things ahead of time, but I remember reading something that you guys - when you played your first live show with Jónsi and Alex at an exhibition in Hot Springs, Arkansas - you intentionally went into that knowing that you wanted to be able to perform everything right there, with loopers, and you set up that initial constraint for yourselves to operate within that space that worked for that night.

Some time before midnight, Thompson and Byrd convened in the dim, pink-lit living room. With guitars, a keyboard and a flotilla of pedals and amps, the pair crafted an hour of contemplative, peaceful sonic textures for about 30 people seated on the floor, on the window sill and on home gym equipment pushed against the wall.

-Sam Eifling, reviewing the premiere and Hammock’s show for the Arkansas Times - an essential read for anyone wondering what Jónsi thinks of the Big Gulp containers at 7-11 stores.

It got me thinking about some of the other shows that you guys have played. There's not a lot of them, but the ones that you have played seem like “bucket list” type opportunities, you know? That one, in particular, to have that be your debut performance seems like a dream to me, personally speaking. I know you've played in New York with Stars of the Lid. You've also come here to Philly to do the Gatherings Concert Series in the past.

After that, it seems like the live aspect of your music doesn't seem to be as big of a focus for you guys. Is there a specific reason for that? Would you be open to playing shows again in the future at any point? Interested to hear your perspective.

Marc: I think the main thing is just…you know, Matt Kidd is always begging us to do shows, to play in the band and be the music supervisor and all that, but like…it's just a lot, you know? What part of our catalog are we going to do? Are we going to do the heavily orchestrated choir with singing? Are we going to do the minimal ambient? Are we going to do the loud post rock stuff? And yes, I'd like to do all of it, but [back then] we were able to put together something that worked where we could take it out and perform it, and I think the only reason that we haven't done it is money. It takes a lot of money to go on the road.

And you know, Andrew and I cut our teeth in our twenties. I was sleeping on an air mattress in a studio when I met Andrew. I spent my twenties dirt poor, and Andrew did too. We were good poor people; we knew how to stretch this stuff. But we traveled, we pumped it out. It was hard work. We slept in the Joshua Tree Park, not because we were wanting to see the sites, but because we went up to somebody and said, “can you let us crash at your campsite? Because we have no money.” [We could] either pay for gas to get back or buy a hotel room, and we have to have gas. That for me is like…I don't want to do that again. That's a young man's thing, and I'm not that anymore.

And also, we've tried to be strategic with Hammock and always think long term: turn down record deals, turn down stuff that we knew we would [cause us to] lose control. It's so weird how some critics or outlets, musical outlets, can't take you seriously if you're self-released, but we're self-released by choice. It's not like…I mean, we've had the knock on the door, and we've done the numbers on what we would lose if we gave up control - not just the artistic part of it. We don't want that, and I think that's the same thing with playing live. We’ve tried to be strategic.

I mean, we accidentally ended up doing the show for Jónsi and Alex. We ended up doing [the show with] Stars of the Lid because Brian loved Raising Your Voice, Trying to Stop an Echo,” and then Adam fell in love with us and booked us for the Wordless Music Event in New York, then got us a gig in Brooklyn at his friend's now defunct club, Monkey Town. So that kind of thing makes sense.

What we would love to do, I think, is probably do a few shows and spend almost nine months to a year promoting it, so that people could fly in and come in.

And I'll be honest with you, we did have an opportunity to work with a huge live booking agency, the guy who started booking the band Phish. He started booking them when they only had seven people coming, and he saw something. And I hate Phish, I'll just tell you right now, but he saw something in them and realized that they could be more than a live show, they could be this experience, and you could play it out over a couple of days. He started listening to our music because he had cancer and he was doing these alternative treatments in Germany, and he had anxiety. His girlfriend said, “you’ve got to get your Hammock on.” He's like, “I don't know what that is.” So he listened to Hammock and he called our manager and said, “you're only the second band I've ever reached out to.” This guy booked everybody. But anyway, we had this thing set up in New York, and we were going to test all this out, but he ended up passing away. I think after that, we landed “Far Cry 5” or something, and we just got into the studio again and then it just went away, you know?

But I don't want to leave this planet having not played another live show, because Hammock definitely is, for me, the most powerful live thing I've ever done. I've seen clubs turn into churches, you know what I mean? It's wild. It's really wild.

Andrew: I'll be the first to say, I'll fly anywhere you guys choose to do it. I'll go…

Marc: And the other thing I'll say too, Andrew, is that Andrew and I…Andrew grew up on a farm, right? I grew up in Arkansas. My dad put me to work when I was 13 at his factory. We have a work ethic. We're from the South; we’re blue collar, we work hard. So when we want to do something live…man, we spend hours, days doing this, getting it right, because we just don't…we want to present the music well, because we want people to have an experience. So yeah, it's a lot of work, and there's not a lot of money, and that's just the reality of it.

Andrew: No, there's not [a lot of money]. Yeah. I can adamantly say [that], especially now in the year 2024. We were playing shows - we've played probably a hundred shows in the last five or six years of doing this, and I'll tell you, now is harder than ever to make it work. It is just so difficult. Really, something did change after the last couple of years we've been through, in terms of people's appetite and willingness to sit through this stuff, I think. Which is sad to say, but I mean, comparing what we were doing in 2019 - playing shows, and the places that we had access to, and the crowds that were coming to that stuff - compared to what we've just done in ‘22 and ‘23, it's a whole different environment out there, which is a bummer. But to your point…

Marc: It is a bummer. I want to ask you a question, because this is true for us. When we were doing shows, you know, and playing out and traveling, and hanging out with people and meeting listeners, for Andrew especially - he doesn't have the ego I do, and I've always said that if there were two of us in the band, we would beat the hell out of each other if there was two of me. So I will tell you that, I think for Andrew, especially, being on the road and playing live really makes him aware - more aware - of what we do. And it makes him more…it makes him feel more like he's “in a band,” and that he's “a musician” because he's playing it live. And I think for him, it's taken a while for him to accept the fact that, you know, we are artists, right? We've been doing this for a long time, but because we were not playing out live all the time, we don't get that kind of immediate gratification of hanging out after a show and listening to all their [comments about the set]… so I'm curious, do you feel more, like, you're more of a musician when you're out on the road?

Andrew: Yeah, it's a really interesting question because I do think it brings things home for me. I wouldn't say I feel like more of a musician, but I feel it more acutely, I guess. I feel it more immediately in the moment, and it's to such a degree that…especially because most of my time spent in Hotel Neon, we’re a trio, so there's three of us and we're bouncing ideas off each other. And that act of playing with those guys, in particular, is really special to me, and I think it's become such a fun experience that we now write music with a perspective that it could be done live at some point in the future, if we needed to. That's always this thing in the back of our head when we're writing in the studio: we don't compromise on what we're doing there, but we do think about, “man, so what would that mean if we were to take this out and road test it, and take it in front of people? What would it take to replicate that? What would it take to do it?”

So I wouldn't say that…yeah, I wouldn't say that I feel like more of a musician, but I feel like it has definitely informed the way I work, because I enjoy it so much. I personally just enjoy that experience of doing it in front of other people, and I've taken that back to the studio with me and it enhances my studio work, I think.

Marc: Yeah. I think for us, when we made Love in the Void after being locked up - and I do think people being locked up and having all that time to contemplate and get real reflective [had an impact]…like, “I don't want to go to a show that's going to put me in a reflective mood,” right? “Enough alone time. Thanks.” You know what I mean?

And I mean, that's what we did when we went in to make Love in the Void. We were just like, “let's hire humans, and let's hang out with humans, and let's camp out in the studio and possibly make an album that sounds the most like a band that we've ever done, so that if we did want to play it out live, we could.” And yep, life happens, and we end up not playing a show, you know.

Andrew: You bring it up, so I'm going to go there right now. Anyway, I wanted to ask about that album in particular, Love in the Void. I think if there was a press release that summed up the energy of an album perfectly, it would be that one.

Breaking from the strange monotony and abnormal norms that took hold during two years of pandemic life, Hammock returns with "Love in the Void", an album that looks to the future, seizes the present, and unabashedly relishes the experiences and bonds that bring meaning to our days. Known for crafting orchestral works of stirring cinematic ambience, on "Love in the Void" the Nashville-based duo of Marc Byrd and Andrew Thompson bring guitar-forward, heart-pounding urgency to songs that shout through and shatter the static of complacency…

…Shaken awake and needing to break free of frustrations and longings, "Love in the Void" pulses with an unbridled spirit for action and experience and a burning desire for connection. Across songs that hammer home the keenly felt emotions of life’s highs and lows, Byrd and Thompson crest soaring crescendos awash in reverb and delve to keenly felt moments of quiet introspection, with unflinching lyrics on tracks like “Undoing” and “Denial of Endings'' that weigh choices made and circumstances that can’t be changed. Lush and dramatic string orchestration from Matt Kidd (Slow Meadow) and emphatic drumming from Jake Finch heighten the stakes in play, and Christine Byrd’s (Lumenette) ethereal vocals leave mysteries lingering in the haze.

"Love in the Void" is Hammock’s loudest album to date, embracing daring and vulnerability with palpable vitality at its core. Wide-eyed and looking forward, "Love in the Void" moves into an unknown future without fear.-Wyatt Marshall

I love the emphasis on the “emphatic drumming,” the sense of “urgency” that's there. It really does feel [like that] and the words describe this very well. I think it does really feel like a shot of energy. We were talking about Maybe They Will Sing… earlier, and even listening to things like the Sleepover Series or what have you, it's a big change from your earlier work. A natural one, I feel like, but it is a big change nonetheless.

So, I'm wondering if during the process of that writing: did you guys have any self doubt about that direction that you're taking? Like, “gosh, this is such a high energy, guitar-forward thing, what are people going to think about this?” And what kind of strategies over time have you developed to get over that inner critic that may or may not be there? I'd love to hear your take.

Marc: That's a great question. Yes, we do have profound doubts. I mean, it's the cycle, right? You start out the record, you've stumbled onto something new, you get this vision, you're like, “let's do it.” And you start doing it, you're like, “Oh, this is great.” Then you get in the middle of it, you're like, “I don't know, man.” And then, you start listening back to everything, and you're thinking, “are these all the songs, or do we need to keep writing?” And then like, “oh man, I think this all sucks.”

And then…somehow there's a shift, and it's usually, for me, having someone else listen to it, who's not familiar with it, and say something that I know is true about it - and then there's a confirmation. I'm not saying that I need people to tell me it's okay to release this one.

You know, this record that we're working on right now is really difficult, because there we have so much material…so much.

Andrew: You read my mind. I'm going to go there in a minute.

Marc: We have a ton of material left over. Our archives are huge, and we're currently looking for someone to oversee that after we're gone, or whatever.

But with, in particular, Love in the Void, we knew that we were doing something different. At the same time, I knew what I was listening to, and I was not listening to ambient music. If I'm just going to be honest with you, there's a seriousness and an intensity about ambient music that I sometimes feel like the theme or the motto for it would be “all serious all the time.” It gets fatiguing sometimes, because it puts me in competition with people, and I think some of [that seriousness] is insecurity. Because, you know, “well, we're fully aware we're making music that's not for everybody, and it's a niche market, and blah, blah,” you know? And, “we're the artists and [other people] are the people who are making a product,” and all this stuff that we end up doing.

And I can get very snobby. I get very…whatever, but at the same time, I don't have to confine myself because [we can] take advantage of the fact that we are self-released. So why, if we're going to go to the trouble to do all the work to release our own records, would we start saying, “we can't do this?” Why? Or, “hey, we want to do this, but let's call it something else because it's so far out.” Well, wouldn't it still be us making it? Yes, it would be. And who makes up Hammock? The two of us. So, why don't we just do this thing…

We are kind of moving towards almost a post-genre type thing. It’s the algorithms that needs to label it something, but people's playlists are much more…there's much more variety now, much more awareness. I love a lot of different kinds of music, but ambient is still probably my favorite. There's something special about really good ambient music, but the truth is there's a lot of really bad stuff out there right now, and a lot of people making it for the wrong reasons: playlists, or health and lifestyle, and I get scared sometimes because I came out of a fundamentalist Christian home. Where I was raised, I burned all my rock and roll records. My stepfather made me burn my comic books and my rock and roll records. I mean, literally, in a bonfire. People wondered, “why hasn't Marc moved on from cassette to CD yet?” And the reason I hadn't is because I could go to a Christian bookstore and buy a cassette and unscrew it, then put the reels of a really good album in there. And when my mom asked me what I was listening to, I could say Petra.

I grew up hearing that music needed to serve some kind of utilitarian purpose to justify itself. I'm fully aware that music can be healing, but that's not why I make music. I make music because music is worth making, and music just for itself is the purpose. That's it. If I put an agenda on top of it, it reminds me of the propaganda element of, “unless it's got this message or this certain thing, it doesn't matter how good the music is, it's not serving the purpose.” And so, I feel like music deserves to be revered, but I also think music wants us to also not take ourselves so seriously.

Andrew: Oh, yeah. I've been like a bobblehead this whole conversation because I could not agree more with what you're saying.

I was talking to my friend Andy Othling the other day, and he and I, we get along really well, but I think a big part of that is because we, we don't take this stuff seriously. And he was saying something to the effect of, “you know, at the end of the day, I just want to play my guitar. I want to hear what comes back into my ears, and I just want to enjoy it. And there's no other - at the start of something, there's no other motive beyond that. Just making that sound is valuable to me and healthy for me.”

And I tell people all the time, too, the work that I do when I'm making music - it's almost like a diaristic effort for me. I'm doing it because it's just what I do. I sit down and like, in the same way that some people write in a journal, or just document their thoughts or whatever, it's just what I do. I can't imagine not doing it. So I totally resonate with with what you're saying there.

I wanted to go back to an earlier point that you made about you guys and your southern work ethic, and the volume of material that I think you've no doubt accumulated at this point. I do want to try to get out of you - it's got to be such a deep well of demos and ideas that you've got available at this point, so I mean, how do you decide when to pull from that reservoir? If you're starting a new project, do things typically start from scratch? Or what happens to that archive? Is that put aside, or when do you decide to revisit that?

Marc: So, usually, okay…

I go to a monastery in Big Sur once a year, and I do a silent retreat. The first two to three days there are hard and uncomfortable, because it's so quiet and there's no phone. There's no service whatsoever, and I become fully aware of how much I'm doing this [gestures at phone] and grabbing for my phone, and thinking I can look something up, and just…it's amazing. So to ease myself into that, I'll bring with me old stuff and I'll listen to it in that space.

I really need to listen to it, because I'm going to go crazy with all this silence around me. And also, silence works on you. It gets you focused. I listen in a way that's very focused, without being overly focused, if that makes sense. In other words, it's not like when I'm listening to a new mix, and I'm just nothing but critic, like “I gotta think about all this,” it'smuch more like, “I'm revisiting an old friend. Let's see if they're nice.” And so I do that about once a year.

Elsewhere, that album that we made during the lockdown and all that, that definitely had some archive stuff that we drew from.

But for the most part, I might say to our manager who is - he listens to everything, so if I say, “I feel like this new album that we're working on is missing this type of song; I'm trying to think of that thing in the archive, what is that?” And he's like, “oh yeah, this is it.” And so he'll send it to me. If that's not the one, he'll say, “well, it's this one.” There are a couple that are on this [upcoming album] that might end up on this record, one that is leftover from…I can't remember what album.

So when is the time to do it? I don't know, but for the most part, I have to start an album new. I just have to, because if I don't kickstart with inspiration, and I just feel like I'm trying to create material so that it can be released, that is not going to work for me. I would much rather bypass some good pieces that are already made, and hope that a good one would arise with what I'm working on now, and all that takes time. And the luxury of, once again, of being self-released is that this type of music takes time. And you have to create enough distance between when you're making it and then deciding to assemble it as an album. Because if I make an album too soon after we're done creating the material, I'll either eliminate something, or I'll put something in that for some reason I've grown attached to because it's just the newest thing we worked on, you know? Man, after about a month of not listening to it and then going back to it, it's not like your child anymore. It's just a thing. I can let it go.

And then the other thing, going back to not taking yourself so seriously: I have to remember that I'm just making a record. I’m not performing brain surgery. I'm not trying to design a bridge so that people can cross, and if I don't do it right, they're going to fall into the ocean. I am literally just making music. That's all.

Andrew: Right, exactly. Yeah. That process of carving and shaping and eventually arriving at a product, that is…that is the work, for sure.

Marc: I love when you've taken the scalpel out and you've cut too much. Especially when it's frequency taming and all of that, you're just like, “well I neutered this song. Great.”

Andrew: Yeah. It's like you're cutting, cutting, cutting, and then all you've done is amplify the things in between all those cuts…God, I'm terrible [at that]. I'll drive myself nuts during that stage.

But you hit on exactly a point that I wanted to touch, too. I know you're fond of Big Sur and those retreats that you do there. I want to understand the history behind that, because I've fallen in love with Big Sur over the years too. I have a deep affinity for the place, and I really love understanding people's attachment to certain geographies and places and how that affects and shapes the person that they are.

So I would love to hear the story behind Big Sur, like how did you find it? What prompted that to be your place, of all the places that you could go? What stands out about Big Sur above the others?

Marc: There's a real personal element to it.

My wife and I went one summer and got a house way up, and it was wonderful and beautiful. I was in a pretty dark spot at that point. This Airbnb that we were renting had a decent library, and I was spending my mornings reading and I just fell in love with the beauty of it. I fell in love with the mornings, and at that time I wasn't much of a morning person, mainly because I had a drinking problem. I went to Big Sur and then I fell in love. I just really loved it. I love Henry Miller and I just love all of that, you know? And the climate - I'm not saying that I enjoy all the atmospheric rivers that are happening right now, but I do love the climate.

And so anyway, I had neck surgery shortly after that, a few months later, and I had to recover. After I recovered from neck surgery, I got to take my first trip. I wasn't allowed to drive for a long time, because you don't realize how much you bounce up and down, and turn and look, and all that. So my wife asked me “what do you want to do?” And I said, “well, I think I saw a sign for this hermitage/monastery when we were in Big Sur, and I want that to be my first big trip.” And she's like, “what?” “I do. I want that to be my birthday present.”

I went out there with the intention of trying to sober up for a little bit, and I did not do well sobering up prior to the trip. I had intentions: two weeks drying out, and then, it'd be a week of drying out. It'd be three days of drying out. [Now] I'm showing up at the airport hungover and I'm getting ready to bail on this trip to Big Sur, and I start [hearing] a conversation behind me. They're not talking to me. [Meanwhile I'm ready] to call [my wife]; I’m like, “what am I doing? How am I going to handle this? This is crazy. I'm in no shape to do this. I'm going to call and tell my wife that I'm sick. I can't do this.” And then these people start talking about silence behind me, and they just keep going…how we need it, and the need for silence, we don't know how to be alone with ourselves and we push silence out of everything…it was just amazing. And so I thought, “well, okay, then maybe I should go on this trip.”

I went there, and about the third night in, I began thawing out and just had a really beautiful moment with realizing that I wanted to live life differently than the way I'm living it, and I wanted to have these kinds of days. I won't be at Big Sur, but I want to wake up aware. And everybody quotes this, but this Mary Oliver line: “one day you knew what you had to be, or had to do. And so you just began.”

I wish it was that easy though, because I had really messed myself up. When I got back, I was like, “I'm done. I'm never going to drink again.” I was drunk in two days, and that's when I realized I had a real problem and I got help.

So I go back to Big Sur every year out of gratitude for my sobriety…it's a touchstone. It's a reminder of what needs to be essential in my life, and what's important. It's a panoramic view of things, because no matter what you do, even when you're doing what you love, it can narrow your vision to a point that you will lose a sense of the bigger picture.

You're just living your little life, lowercase, and you're missing out on life, big L. And also, just the nights in Big Sur where I can lay down on a bench and look up at the stars and see 21 satellites in 30 minutes…I don't know about you, but man, listen to Hammock there. Woo.

Andrew: I've done it. Yep, I've done it. Those winding cliffs…yeah. God, there's just nothing like it.

Marc: I've done it 10 years in a row. So, that was 10 years ago when I did that, and I go back there because It's like a spiritual home to me in a way. Not because it's a monastery, but because it's just a place where…it just resonates with me. I can't explain it, and I think it’s really good that I can't explain it.

Andrew: Yeah, exactly. There's some power in mystery. I totally agree with that.

Marc: I don't want to tame the mystery too much. Somebody told me when I was trying to get sober, “Marc, you've spent your life analyzing the mystery, sitting outside the mystery, trying to figure it out. The best thing I think you could do is just be part of it.”

Andrew: Well said. Just sit in that, for sure. Man, that's a really powerful story. Thanks for sharing that. I was always curious about the meaning of that place for you, so thank you for sharing.

That is actually a good segue into another question that I had. I'm going to tee this up, so bear with me while I try to get this out, but I will land the plane at some point.

When I think about the music that you guys make in Hammock - I actually wrote this down, because I was trying to think, “what does it do to me? What do I feel?” And to me, what I came up with was “battle-scarred optimism.” It seems like your music is kind of like…there's an aching to it, and there's a longing to it that feels like it's acknowledging grief that you've been through, but I still come away from it every time I hear it with this understanding, or this acknowledgement, that things are going to get better.

And I know you've been open about tragic events that have happened, with certain albums. I'm thinking about Mysterium, that came after the horrible tragedy where you lost your nephew.

Songs like Marathon Boy really stick with me. I well up and I get a lump in my throat every time I think about the Boston Marathon backstory to that.

“This is for Martin Richard, an 8-year-old boy killed in the Boston Marathon bombing. He appeared to reach for his mom in his final moments. His story and the grief his family went through really hit us hard. The unspeakable cruelty we inflict on one another… it’s absurd. Who needs supposed ‘acts of god’, we’re doing ourselves in just fine. We fall silent during these times so we create to console ourselves.”

-Marc Byrd, Clash Magazine, 2016

You've been very open in acknowledging all this ugliness in the past, but yeah, there's still something about that sound that feels like you're kind of reaching for things that are on the other side, or reaching for the light at the end of the day, and the music closes the loop on all that grief.

So, with all that said, I'm wondering if that resonates for you, and do you feel that your personal outlook on life comes through in the music in that way? Is that kind of searching for peace, or looking for the “after” of the hardship, a part of the sound? Are you generally an optimist about things?

I’d just love your perspective on this. If I'm just blabbering on about nonsense, then let me know.

Marc: This is really the thing we hear the most from people, that there's an ache and a beauty at the same time. And I mean, to simplify it, many people just say, “I feel happy and sad at the same time,” or whatever. But it is not at all to get me to the other side. It's to companion me through whatever it is. If I’m always thinking that I'm eventually going to get through this, I'll miss what I'm going through. What's in the way is the way, as they say, and the only way through is through.

I spent most of my life trying to get somewhere, and for the music to companion me through whatever it is, it can remind me that there is light at the end of the tunnel, as you said. But it also can remind me that there's light in whatever it is right now that's going on, even though it's a speck.

You know, I've always described it as when you walk towards something, and you're in darkness. It's not being able to see the city lights clearly, it's just being able to see a little speck of light and you just start walking, not even able to see your feet in front of you. That's what it feels like when you go through profound loss. And so, I told my wife this one time; I said, “I just think our music is what it sounds like to be here. That's what it sounds like for me to be here.” And she's like, “Oh, that's sad.” [laughs]

But the truth is, it really is.

I grew up hearing simplistic platitudes and clichés, and an emphasis on this artificial joy; this artificial sense that things are okay when they're not okay. Clearly, they're not okay. I got dubbed as “defiant.” I mean, you've heard my story. I've struggled with all that stuff since I was 11, to be honest with you. I could go into this, and it is…When I tell people about how I was raised and all that, people are like, “what?” It's borderline cultish crap. I wasn't allowed to be okay with my feelings, and so what I love is when people [say that] Hammock hits them so hard, they're like, “I don't even know if I can listen to it again.” Because it scares them; it puts them in front of themselves.

And that's the thing about good music. It pulls things out of us that maybe we don't want to look at; things we've been ignoring. It brings them to the surface.

One of the great stories is that when Andrew and I were hanging out with Timothy from Strand of Oaks backstage. His attorney was there, and he was like, “you’ve got to meet the guys in Hammock, blah, blah, blah…you got to go home and listen to this stuff.” And then the next day, I'm looking at this guy's Twitter feed, and it just said: “last night, I went down the Hammock wormhole. I realized I need to call my dad.”

Andrew: Oh my God, that's so perfect.

Marc: That's just…that's a micro of a macro, right? That's it right there, you know? And man, I just love that. Because calling your dad - like my dad just passed away, January 4th. So I'm walking through that right now. Calling your dad, for me at least, was a mixed bag…like, “I need to call my dad. I miss him, but what's it going to be like? How's it going to feel?” And so…I do think we process grief through our composing of music; the way that we compose it, the way that we sit with it. I've said in other interviews that sometimes I have people's faces [in mind], they just appear. People that I lost when I was very young, and I'm aware of them. I'm not saying they're in the room with me, I'm just saying that I'm very much aware of the fragility of things. That is both sad and sobering, but also really beautiful. If I let that impact me in the correct way, not lead me to despair, it may make me not want to waste my life.

And I'm not saying it like…I don't want to overdo it with Hammock. I just know this about our music, not because I automatically thought it was going to be this way. It's because over time, I've just heard the same thing so consistently: that it’s beautiful and painful at the same time. And if I don't know a better definition of life… that's it right there.

Sometimes we stub our toe, and our whole body becomes our toe, and that's all we can feel. That's all we are. But there's a whole part of us that's not splintered yet. That's it. We're okay. But when we're in the midst of that darkness, I don't want someone telling me to “feel better” and all that. I want to know, “have you been in the darkness, man? Really? And you made it through?” “Yeah, and I'm not going to lie to you. It's gonna suck, and hurt, and it's gonna stretch you to places. It will bring you to the end of yourself.” But that’s part of it. That’s just existence, life on life's terms. That is as it is, and what it is, and the best thing to do is put yourself in a good relationship with reality, rather than always standing against it.

And when I hear people say [the music] stirs up so much, it reminds me: my stepfather used to talk about how the music would make him feel, and he was scared. “That doesn't feel right,” he would say. “That's demonic, that's of the devil.” Looking back on that, I just realized, like, he was just scared of feeling, just scared of how much is stirred in him, because it created a sense of…it put a crack in his certainty, and it made his world more afraid rather than less afraid. But also more exciting too! Oh my God, you know?

And I just think that art has always been that way. People are always like, if they can't explain why it makes you feel something, they just say it's cursed or it's this superstitious crap that we believe in, you know?

Andrew: Its job is to hold a mirror up. And if we don't like what we're looking at, then [those negative feelings are] only magnified.

I know a lot of people like your stepfather. It's a scary place to be - I can only assume - for them, when that kind of crack occurs and there's…

Marc: It is. It's disorienting. I mean, I don't want to ever…most people don't want to go through that, because it's a reconfiguring of your whole life.

Andrew: Right. Exactly.

So I don't know how to follow that up, but I'll bring it home here with one last question that I wanted to ask. You and Andrew have been making music for a long time now. But there's also been a good bit of collaboration along the way, too. I'm thinking of The Summer Kills, and all the work that you've done with Matthew Ryan.

You guys just recently reinterpreted some music with Yellowcard, of all people, which I think caught everyone by surprise. And I love that you're willing to…

Marc: I’ll be honest with you, it’s weird…my whole thing about “all serious all the time” was because some people are just not happy about us doing that. But man, Ryan's one of the nicest guys I've ever met. He's a huge Hammock fan and loves this kind of music, and was going through a really dark time in his life when he reached out to me, and we just started hanging out and talking. He was like, “what if we reinterpreted these three songs?” It was just going to be for him, but then Yellowcard got back together and they started getting all this crazy attention, and we ended up doing nine songs, and it…I will just be honest with you, I need to do things like that because it resets my mind. It resets it, it opens up enough space for me to not be overwhelmed by Hammock all the time.

Andrew: Yeah. And that's kind of the first part of my question, I thought exactly of what you were saying earlier when you mentioned the need to not take things too seriously all the time. But when you're writing music that is highly emotional and charged like that, do you have consistent sources of release that you go to? Non- musical. I'm wondering how you get your head back on straight after going through an experience like writing a Hammock album. I have to imagine that it's a pretty emotionally exhausting experience to go through, and I'm wondering how you recharge from things like that. How quickly are you ready to get back up in the driver's seat again, after going through something like that?

Marc: Oh I'm not ready to get back…Well, you know what? That's crazy, because sometimes when we get to the end of an album, we're so tired of working on that album that we start working on new stuff automatically, like a cathartic release.

But for my own personal wellbeing…it's very personal, and so I don't want to break anybody's anonymity, but I have a group of people that I am very close to and connect with. And we meet around the fire every Monday night. We meet for an hour and a half, and we talk stuff out and we let things out, and we help each other and support each other. Also, my wife and I, we just love to be with each other, you know? I mean, we went through a hard time on that first trip to the monastery. We were going through a rough time. We've been together for a long time, and she's just a real balance for me. She's an artist herself. Her degree is in classical voice, and so she understands that, and she's a beautiful human being.

The other thing I would say is that I read a lot. I like to go out in nature a lot. I meditate almost every night. I do some in the morning, too, but at night, during the lockdown, three of us - one’s in Seattle - decided at nine o'clock we would get on Zoom, and we would sit in silence and meditate for 20 minutes. And we've done that for three years…since 2020. And we keep doing it. I don't do it every night, but you know, it's four or five nights a week. Saying it holds me in a place where - sometimes people don't do what you expect, they do what you inspect, you know? And so I feel like I need to - they're expecting me to show up, and so I better go. I literally have to open up my laptop and sit there, and I'm like, “sorry, honey, I know we're in the middle of this, but I’ve got to meditate.” And that helps a whole lot.

And I have a lot of guys that I help with the journey of sobriety. I'll just say that a lot of my time is in a place that I never want to end up in again, once a week, because I just want to remind people that there's life after you put down whatever it is that you've been using to cope, and you're going to be okay. So that's very enriching.

Also, my wife works with special needs kids. And so when I go upstairs and complain about somebody not playing in tune, and I can't get something in time, she tells me she changed the diaper of a 13 year old and I just automatically realize, “Oh, all right. That's perspective right there.”

Andrew: Yep. 100%. And yeah, shout out to Christine. I love your credits for her “angelic vocals” that show up on so many of your guys’ records.

Marc: I wish you could sit in a session with her and watch her work. The way she doubles, triples the harmonies she hears, I mean, it's just…it's astounding. I would love to make a record of nothing but her voice for the instrument, just layer and stack. That's a dream of mine.

Andrew: I love her work as Lumenette too, so yeah, that would be a dream.

My wife, too, is a singer. She grew up a theater kid, had dreams of being on Broadway one day, but yeah, she can really belt and she's been on some of our music too.

I am so jealous of people who can harness their voice in that way. I have no [vocal] ability whatsoever, so I'm very jealous of people like that.

But yeah, I guess the second part of the question there…I asked about “non-Hammock” things, so bringing it back to musical stuff a little bit, to the Summer Kills and the Yellowcard collaboration. Are there any other non-Hammock projects or ideas that are waiting in the wings at this point that you haven't been able to fully explore yet? Anything you can share that might be popping up in the future?

Marc: We have something that I cannot share with you. It’s just one song. It's one song, but it is happening. And this person has…I've noticed him being a fan on Instagram over the years. He's also a Southern artist. He invited us to come look at some artwork in the past. There's a song that's done; we're waiting on them to send the files, and it's a collaboration that I'm really excited about. I sought it out; we weren't sought out. I sought it out. Or shall I say, our manager [sought it out], so that I could, if I was rejected, I didn't have to deal with it…I could just indirectly be rejected, and soften it.

But it's something that we're really excited about. Right now, I get videos of them working on it and I'm like, “Oh my God, this is happening.” I have a rough [mix] of it. It's something that I think will be on the next record. It's in the vein of Love in the Void, I will say that, but it's a “song” song, and the lyric is pretty dark. So, yeah, we like that.

Andrew: Whatever it is, I'm eagerly awaiting the results there.

Marc: Matt Kidd keeps trying to get me to do a Substack, or he tries to get me to do a podcast. I mean, it's just something…I think basically he'd like to be a co-host, just so that he could hang out with his uncle Marc and listen [to my advice]: “hey Matt, you're not crazy. You're just a really weird, artist type guy, and you have a kid, and man, life's weird.”

Andrew: I love Matt to death. If you're listening, Matt, we appreciate your efforts. We love you.

Marc: He says he’s done violins yesterday, or the day before, and he's going to do cellos on Monday. I think he's doing four songs for us by the end of the week. I love me some Matt Kidd.

Andrew: He's a wonderful human being. Always love hanging out with him.

All right, wow. Well, thanks Mark. That was a really, really fun conversation. Thank you for opening up about so much of this stuff and entertaining my questions here. Really enjoyed the time. Thank you.

Marc: Well, I hope I didn't let you down.

Andrew: You did not. You definitely did not.

Marc: I really appreciate you having me on. This has been a wonderful conversation. This is really refreshing.

Andrew: I'm glad I could be that for you. Happy to help. Well, thanks Marc.