Welcome back to the Sound Methods podcast. First, I apologize for the long break between episodes. I know it's been many weeks since our last episode with Chris Carlson, the developer of Borderlands Granular, back in May. Be sure to check that out if you missed it the first time around:

It takes me a while to prepare for these interviews. I like to ask questions that yield insightful answers and aren't just asking the artist to rehash things that we can read in press releases and other interviews that have already been conducted. To make them original and insightful, it does take a little bit of time to think through how to approach the questions and I've just not had the time to do that…but rest assured, we're going to get back into it in short order here. I have some guests lined up that I’m really looking forward to speaking with.

A quick note about podcasts, too: I'm working on adapting some of the studio diary posts that I do on Substack into audio format for podcasts. I'm pretty excited about this. I think it will make for an interesting listen as I talk through what I do and how I do it. You’ll hear a song evolve over time, and I'll share sound samples while I literally talk you through what's happening to have an audio format of the diary accompanying the written version. Stay tuned for that - I'll be getting started in the relatively near future here.

Sound Methods 009: Scott Campbell

Today's guest is Scott Campbell. I knew as soon as I started the podcast that he would be a guest at some point, since we've run in the same circles for quite some time and we're label mates on two different record labels: Seil Records over in Germany, and then Mystery Circles here in the US.

I've always loved his music, which is evocative, emotional, and filled with so many textures and interesting layers. You can tell that there's a real human being behind this stuff - even before you see his hands flying around on-screen in his YouTube and Instagram videos. Nothing about the music is cold or distant, like a lot of synth-driven ambient music can be from time to time.

As a fan first, it was interesting for me to hear him talk about how he works and what he’s learned over the years, and I think it sheds a whole new light on the work that he does. I came away with a whole new appreciation for music that I already loved, and now love even more. I especially loved getting to hear him talk about the other, non-musical aspects of his artistic life: he's a graphic designer, an illustrator, and an instrument maker, and all of that factors into the work that he does.

Please be sure to support Scott by purchasing his music over on Bandcamp: https://scott-campbell.bandcamp.com

You can also view his graphic design and photography on his website. There, you can also find links to all of his social media channels, as well: https://www.scttcmpbll.com/about

Finally, check out his instruments by visiting the Onde Magnétique website: https://www.ondemagnetique.com

Transcript

Andrew: All right, Scott Campbell…welcome to Sound Methods. Thanks for joining me here.

Scott: Great to be here, man.

Andrew: Absolutely.

I was thinking about it, and the ambient world is so funny. It's a relatively small number of people spread across huge distances. This is our first time talking “face to face,” and we're actually label mates on two labels now: Seil Records in Germany, and then also Mystery Circles in Las Vegas. Germany, Las Vegas, Philadelphia, New Orleans…the geographic spread here is pretty impressive. It’s really cool that we finally got to make this happen, and I'm really looking forward to speaking with you in more depth here because you've been on my radar for a long time now. I've always loved the work that you do, both visually as well as audio, so it's really great to have you here on the show.

I'm going to start with a question that I tend to come back to when it comes to guests here on Sound Methods, and I ask it because I think hearing the artists explain it for themselves is an interesting way to get at their thoughts and motivations and intentions behind their music. But the question is always, “how do you define what you do?”

How would you describe your music to other people if they were to ask what you make?

Scott: Oh man, I guess it depends on who is asking. If it's someone who doesn't really have any frame of reference, then I would just say it's “soundtrack music” or “it's instrumental, but some sort of emotion is conveyed without lyrics.” That's the base definition. Aside from that, I don't know…it's hard to pin down.

I'm sure it's similar for you and a lot of other people, where it's process-based. I'm not a singer songwriter, so I'm not necessarily pulling from specific things that happened to me in my life, or whatever. It's more like I'm experimenting with different systems that I'll set up, or processes, and then find things within that. Things evolve and snowball from that. So I guess, “ambient” is a good catch-all.

I think this is something I've seen you bring up before - I'm not trying to make “new age” or the “healing” ambient. I like a little bit of melancholy in all the types of music that I'm into, and I think that is a much richer place to start from…in my opinion.

Andrew: Yeah, absolutely. I can go a couple of different ways from that response and from this question. It's interesting, in my opinion, to talk to ambient, experimental - whatever you want to label what we're doing here - it's interesting to talk to people in this space because it's not like other genres, where the instruments that you're using, or the tools that you're using, are so central to your identity. With laptops and samplers, you blend into the background, more or less, and your role is a lot more ambiguous than if you're talking to a jazz musician, where their identity is inherently tied to the instrument that they're playing: you're talking to “the guitarist” or you're talking to “the bass player.” And that’s not really the case with the music that we make.

I'm rambling there, but I'm wondering how you feel about this and if that makes sense, or brings up any thoughts in terms of how you think about your approach to music. Because I know that you use a lot of synthesizers in your music - it's highly textural and synth focused. But do you think of yourself as a synthesist, or is it something more than that? Are you trying to paint a bigger picture?

Scott: Not really, because especially now, a lot of the places I start from are more sample-based. Not “sample-based” as in pulling from records, but just found sound and other things that are thrown into a sampler and then turned into [something new], whether it be a polyphonic sound or a percussive sound, whatever.

But to your point of the instrumentalists, I started as a bass player. You did too, right?

Andrew: Yeah. You read my mind. I was going to go there eventually. I would love to hear your origin story [with the instrument].

Scott: So, I started playing bass when I was like 15 or whatever, and played in many bands. I was into the Herbie Hancock, jazz fusion, Miles [Davis], the “electric Miles” thing…and I guess that's really where I started getting into more experimental sounds. Not that there was a whole lot of synthesizers going on - maybe in Herbie Hancock there was - but that approach is something that bled over into what I wanted to do.

I don't necessarily consider myself a synthesist now. Moving from being a bass player to making electronic music, I almost think of [my role] as more like a producer, where you have more of a diplomatic view of every part of the process and everything is focused towards making the best piece as a whole, whereas you don't really have that focus as a musician or instrumentalist. Every decision seems a little more selfless, because it's all just part of the bigger piece…whereas, as a bass player, you're like, “I’ve got to get my part really sick so everybody knows how good I am.” [laughs]

Andrew: Yeah. That's funny, I resonate there. I think with my past as a bass player, I've always…I come from a history of, like you said, playing bass, playing in bands, and being a sort of foundation for other people. So it's funny to think about, because in my current music that I'm making right now, I end up thinking about the piece as like, “where do I start and what kind of a foundation do I lay, and then build on top of that?” Everything is viewed from a “bottom up” perspective, and I think I definitely pull that from my bass playing days where I was setting the foundation for the guitar parts and for the vocalists that I played with. I still think that way today.

Scott: Interesting. I know you still play bass a lot, but I'm so far removed from it. I'll pick it up every now and then, but I guess I'm just so far removed from it that I don't even think in terms of being a bass player anymore. A lot of the stuff I make wouldn't even really have a bass line. Maybe just something in the low register to round out the frequencies, but not a bass line in sight, really. And I played drums for many years too, and now I'm making music with no drums or rhythms, for the most part…which has changed a lot recently.

Obviously, the things that I've put out prior to now are drumless and pretty much rhythmless, but I think it’s the same thing with what you're experimenting with. I'm just wanting a little bit more to grasp in the pieces, and moving towards rhythm is an easy way to get there without overdoing chord structures, or things that would pull it out of the “ambient” world or something.

Andrew: Yeah, and that's a good place to go next, actually. I was re-listening to some of your discography, and I was listening to “Photos from the Flood” the other day. And then I went chronologically from there: I started with “Photos from the Flood,” and then all the way through to “Quiet Rituals,” your most recent one from 2022, I think.

But from what I can tell…and this is just my take; you can chime in here and I'd love to hear your thoughts on how the things have progressed over time, but it seems that I get a progressive sense of calm and space. On “Photos from the Flood,” I felt like there was a lot more happening. There was intricate layering of many different variations of sounds, all interacting together. And then you compare that with “Quiet Rituals” most recently, and there's lingering sound hanging around with much more durational layers in there.

And I'm wondering if you resonate with that. How has your approach changed over time? And then, you hearkened on it a little bit there, but where do you foresee yourself going, next?

Scott: Yeah, it's definitely a conscious decision. It’s striving for saying the most by also saying the least; the strive for minimalism, but still having a really strong voice. I’ve just been listening to a lot of things like Alva Noto…these guys are just so minimal, and I'm like, “how can you get away with that? I want to get away with that.” Doing as little as possible and still having it be compelling.

I've moved in a “less is more” direction. Partly just cause when I listen back to older work, I'm just like, “there's too much shit going on. It's just if you let things breathe, then people become more focused on texture and timbre and things like that, and those are the things that I'm more interested in. I am interested in melody, but things like specific chord progressions or anything that's more “traditional” is not really what I want the listener to be focused on. When you give their ears room to breathe a little bit, it lets them pick out all the pieces or hear the complexities more, which is counterintuitive. You would think more complex music would seem more complex to the listener, but when you give them a little bit of space, the complexities come out more than something that's busy. It's hard for the brain to grasp one thing and really appreciate it. Somebody like Aphex Twin can make something extremely complex and it still works, but I'm not Aphex Twin, so I'm trying to make things easier on myself, is basically what I'm saying.

Andrew: Yeah, an admirable goal. It's interesting to hear you confirm that, because that was definitely the sense that I got.

And I should also mention here, too, you've done work in the past with Geoff Dumont. I love what you guys did as Bell Mountain together. I think it's really beautiful and definitely wanted to shout that out here. Especially that “Tertiary Colors” EP that you guys made together. I'll throw a link to that in the article, of course, but I was hoping you could talk a little bit about your methods and artistic approaches for that project. How does your approach change when you're collaborating with another person?

Scott: I should mention that Jeff actually, unexpectedly, passed away like a month or so ago.

Andrew: Wow. I'm so sorry to hear that.

Scott: It was a shock. Yeah. He had continually sent me things in the Dropbox, so I have a stash of his unreleased things that I'll probably put up on a Bandcamp at some point for everyone to enjoy.

But we both came from band backgrounds, of course, and we were friends for many years. And when I moved to New Orleans, I wasn't really playing much music and he wasn't really either, but we both were tinkering with electronics and stuff like that. We just started getting together and screwing around and making little recordings, and eventually it just became Bell Mountain. The first thing we did together was pretty much all collaborative in the room together. But that last record we put out, “Tertiary Colors,” was more…he would come up with a few tracks, a few things that were just ideas, and I would expand on them. For that record in particular, what we did was record everything to tape and slow it down, and throw echoes on it and do a lot of the “dub” trickery - even though it's not really a dub record, it has a lot of those tricks weaved into it.

I think we worked well together because he was always recording things and always active hitting the record button, which I'm bad at sometimes. But I am really good at finishing a track and pushing it out, and putting it on a record and doing the art and coordinating all those sorts of things. So we worked well together in that regard. It spanned the gamut from working in the same room to doing the “trading files” thing, and it was always super easy because I'm pretty opinionated as to what needed to happen, and he was super easygoing. So that worked out very well.

Andrew: Yeah. It's always nice to have a complimentary personality like that in the room. I like hearing people talk about this, too, just because the ambient world tends to be a lot of solo, individual efforts. I’m curious to hear, do you have any kind of preference when it comes to working with other people? Do you find that collaborating with others, even just a remix or something like that, does that kind of unlock parts of your brain that you enjoy? Would you like to do more of that in the future?

Scott: Yeah, for sure. It's nice because there's two sides to my personality in that regard. Obviously, when I'm working on things on my own, or in general, I have really strong ideas of what I want to do or what the sonic vocabulary is, or however you want to say it. But when I'm working with someone else, I let go of those things and it almost makes it easier and more fun, just because I know that I don't have to hold on so tightly to it.

And especially in the case of [working with] Geoff, or like a remix, starting from a place where I already have all these sounds to work with is really fun. That's how I work when I work on my own, is I'll separate sessions where I'm basically just collecting sounds, building patches, coming up with different techniques…I'll do that in a separate session before I'm even like, “writing music,” quote unquote, or recording a finished piece, so that when I sit down to do the finished piece, I basically have the vocabulary defined. It just makes it so much more fun than sitting down and trying to start from zero and make a track - which is not to say that's not the right way to work. It's just that the older we get, the less time we have, so I'm trying to compartmentalize the aspects of the music-making process. Doing a remix would be the same sort of thing, because you're starting with material already. I'm actually working on a remix right now, and it's just nice because it's all the second half of my process. I don't have to do any of the other stuff. [The first half; making sounds] is tedious, but I also love it - all the patch design and things like that. Obviously I love that nerdy stuff, too.

Andrew: Yeah, I totally get it. I work so much better when I have a starting point. In every band that I've been in, I've been the guy to chip in after the fact, or to help carve stuff out from a foundation. I've done it, but I don't particularly enjoy that start of the process, like getting an idea formed and getting it going. I think that's why I gravitate to sample-based processes so much, because there's already a sound to meld and to shape and work with.

Scott: Exactly. That's like my last record, “Quiet Rituals,” I basically would just spend an evening making loops. I set up a Frippertronics system where I was recording tape loops that would degrade over time. I would just do six to eight of those all in the same key, and then I would have a batch of degrading loops that I'll work together. I basically just live mixed those to write the song, or perform the track. It's just so much fun doing it that way, because it's all creativity and fun at that point…there's no tweaking really. It's all just listening and reacting.

Andrew: Exactly. That “reacting” part is exactly what I was going to say. You took the word right out of my mouth.

I found this old Dropbox folder just the other day, and it's filled with all these loops that I don't remember making. A bunch of piano parts and other things. I'm just having the best time listening to whatever it is, and whoever I was when I made that, whenever that was. I don't even know - there's a date on the file, but I don't think it's totally accurate. But yeah, just listening to that and responding and letting those kind of shape where I choose to go is definitely helpful to me, and much more fun than trying to come up with a chord progression out of nowhere. I think that's why I gravitated to ambient music over time.

Scott: Yeah, I agree. I'm not a songwriter…it's funny because, obviously, I listen to a lot of the music you would think I would listen to, but a big part of what I listen to is just singer/songwriters.

Andrew: I'd love to hear - what are you listening to for inspiration, even if it's the unexpected kind of stuff?

Scott: In that vein, like the singer/songwriter thing, I'm currently obsessed with Jessica Pratt, who just put out a record. I've been listening to her for a few years and I think what it does is, it sets the emotional bar. A singer/songwriter can just get to that point, that place, so easily because of lyrics and voice, obviously. It sets this emotional bar that I want to get to in my music. Instrumental music doesn't really get there in the same way it can, but just knowing what to shoot for is helpful in approaching my own music, even though I'm not doing anything remotely similar to that.

Another one would be like Adrianne Lenker, who's the singer from Big Thief.

And of course going back to things like Leonard Cohen and Elliot Smith and things like that. Beyond that, the things that I listen to that are more directly influential, I think I've talked to you about Topdown Dialectic being a big current influence. It's probably the thing I'm listening to the most right now.

Them and Purelink, which I had also thrown out to you before.

Andrew: Yeah. Thanks for making that recommendation…Oh my God. I dove headfirst into the deep end on their stuff. I've been listening to every Lot Radio session that they've done and I've got “Signs” on repeat. There's a great Substack account that I love listening to for recommendations and everything called . They recently reached out to me to ask if I'd like to make a recommendation on their channel, and I went to Purelink, because it's made such an impact on me over the last couple of months. I have you to thank for that.

Scott: Oh, that's awesome. Yeah. The big touchstone for me right now, trying to get more into the rhythmic thing, is Jan Jelinek’s “Loop-Finding-Jazz-Records.” It's like the blueprint.

Beyond that, there's this Instagram account that I follow called Minimal Collective. It's really more techno-based, but I think weekly, they'll highlight three records and a lot of times it is very ambient, minimal techno. I found a lot of good stuff through that. I find that there's this whole world of mainly European artists that I'm not really privy to, because I've never really been immersed in the techno world, and a lot of them are using textures and techniques and things that the ambient people are using. A lot of it’s dark, a lot of it's a little more brooding, and of course, there are more rhythmic elements and things like that. I’m trying to dive into that more for inspiration, even though what I end up making might not be in that vein, per se. But I’m always looking for the next spark of influence.

Andrew: Yeah, it's funny, because you talk to people who have been making ambient for a long time - I can think of a couple friends of mine that I talk to about this stuff - but a lot of people come to ambient from the techno world, or like the IDM space or generally more beat-driven electronic stuff. And then they kind of gravitate to ambient as the “chill out room” diversion in their journey. But I'm going the opposite direction. I started in the chill out room, and now I'm like working my way towards the dance floor over time as I get older. It's funny how that works out.

Scott: Yeah. Whatever works.

Andrew: Exactly. And gosh, yeah, you said a lot there that I could take in a couple of different directions, but one place I want to go to is your visual art. You mentioned it's hard to tell a story with instrumental music and the kind of stuff that we're working on. You don't always have narrative devices or storytelling mechanisms like lyrics or vocals or things like that, so it's a challenge. It makes for an interesting exercise in self expression. But I love talking to people who have multiple artistic disciplines to tap into, and you're a graphic designer and illustrator in addition to your music-making. I'd love to hear you talk about like the contrasts there.

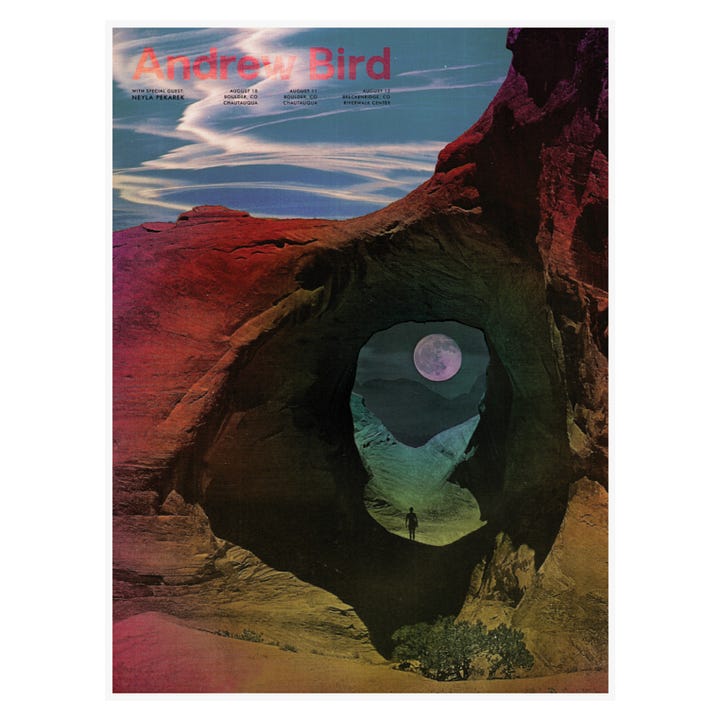

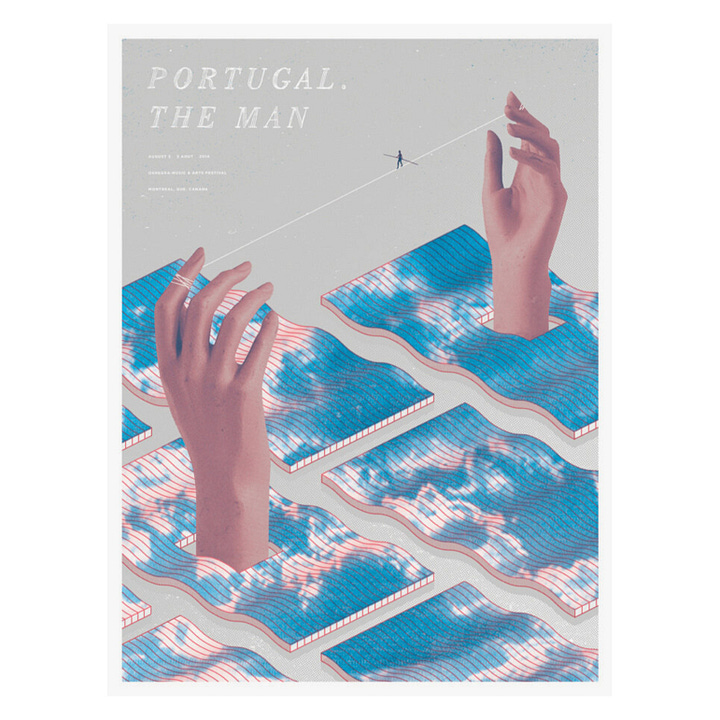

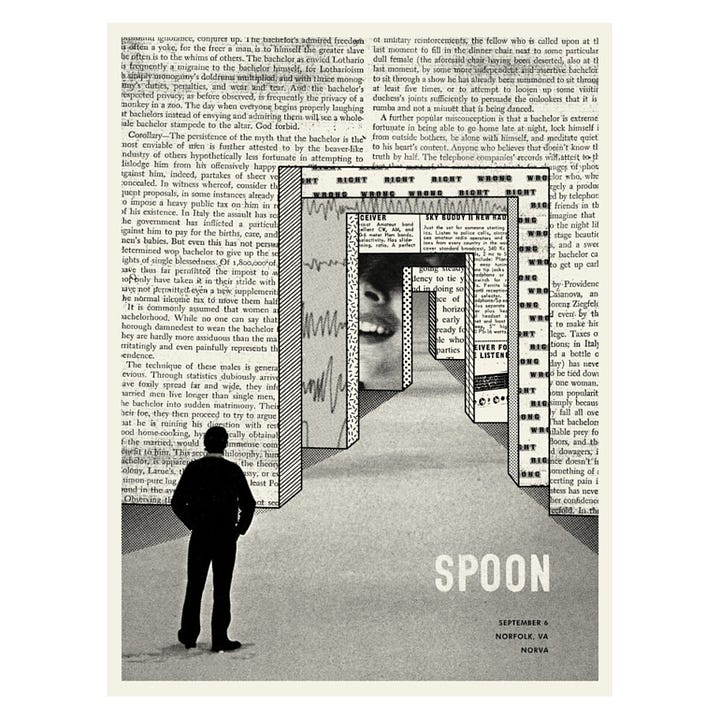

You've done some amazing show posters for Andrew Bird and all kinds of artists, and there, you're presenting specific information to an audience…whereas with ambient music, you're like, “here's my thoughts and feelings but without any kind of clear indication of what I'm actually thinking about.” Do you find it easier to express ideas through visual art or through music? Does one or the other give you more satisfaction, or is it like a balancing act between the two?

Scott: It's the kind of thing where they both feed off each other, and they both ebb and flow in terms of which one that I'm more focused on at a given moment, because I tend to get tired of a certain discipline. Or not even necessarily tired…say that I'm working in a certain graphic style for a period of time. I just get tired of doing that and I'm not sure where to go from there, so I can focus more on music and not even think about the graphic stuff. Then, the time away is what ends up making my graphic work in the future better, just because I've had a chance to step back from it. The back and forth has always been a part of my life since I was a teenager. and, it's also like they both influence each other. A lot of the times I'm more influenced to make music based off of artwork or architecture or sculpture, and obviously a lot of the artwork that I've done has been influenced by music.

A lot of the music posters and album work and stuff like that that I've done, I think that's easier to me because if you're influenced by something in the genre, if it's really close to you, it's hard not to like, just do it [yourself], and do that thing. You know what I mean? It’s hard to step away and be influenced and have a creative vision that's not the exact same thing that you're influenced by. So pulling influences from all over has always just made things easier.

A big thing I'm into now is architectural stuff: I see a building or a place and the aura and the vibe of that location makes me think about what music would enhance that experience. I think that's just a good way to look inward for inspiration, because obviously the architecture itself is not going to define anything about the specific choices I make when I'm making the music. It's more just like putting your mind in the right place to do something.

Andrew: Yeah, absolutely. You've got some amazing designs on your website that I'll definitely link to in the article, that you've done in the past.

I'd love to hear more about your history with, graphic design and illustration. Is that something you went to school for? Did you know you wanted to do that, or did you happen into it? What's the beginning there?

Scott: I was an artistic kid, just drawing and that sort of thing, so of course, when high school rolled around, my parents were like, “you should do graphic design.” I was like, “what the fuck is graphic design?” In the past 15 to 20 years, graphic design has become pretty popular and pretty cool. But in 1996, it was not a cool thing that people did.

I went to school for that for a little while, and I ended up going into a phase where I became more focused on music, so I really didn't care about design school at all and ended up dropping out. I worked my way back into design through music, through knowing promoters in town and knowing bands in town and just doing posters. At that point, there was a website called Gig Posters where a lot of people, big and small, were posting their artwork for bands - posters and things like that. It got a lot of traction, and I got a lot of jobs out of that and made a lot of friends. The art director at Chase Bliss, Eric Nyffeler, I met him through that website. There's just a lot of great people doing really awesome stuff, and we all met through that website.

Andrew: Eric's interview on the Object Worship podcast was super cool. I loved listening to that. That's something you take for granted, the visual layout of an effects pedal and what the graphics make your brain think to do, and where your hands feel led. It's a super powerful medium.

And bringing it back to work that you've done, I adore the photographic elements that you have in Photos from the Flood. I think the textures and manipulations that you did with those Polaroids and photographs are such a powerful compliment to the music.

It's one of the better examples, I think, of the relationship between a visual and a piece of music, where like they're very closely connected together. It's very obvious to make that connection there.

I'm not steeped at all in, in visual art technique. I look at a blank page and I can't envision anything there. Some people have that gift, right? They can just see stuff and materialize it for themselves, but I can't, and so I'd love to hear you talk about what are your influences in terms of visual art: do you have preferred aesthetics, and how do you think about your photography and graphic design? How would you describe that to someone like me, who knows nothing about visual art?

Scott: They're so different - the Polaroid stuff and the graphic design stuff that I've done. It's all over the place, a little bit. The “Photos from the Flood” thing worked well because it was just a really organic theme. My parents’ house flooded really badly, and I went through their photo albums to salvage photos. I was just blown away by seeing a lot of photos I had never even seen before, but a lot of them were destroyed in these really interesting and beautiful ways, and so the emotion within that whole occurrence, that whole event of that flood and everything around it was just like…

In a creative context, it's hard for people that make music like us a lot of times, because I think we feel pressured to attach some sort of narrative and ideas to the music, and it feels forced a lot of times. Even for me. The past two records that I put out on Seil, I basically wrote a one or two sentence [statement], like “this is where I was at.” I don't want to create some fake narrative or something. The “photos from the flood” thing just fell into place and worked for that time period, and the photos that I made for that were not the ones that I recovered from my parents house. They were all new photos that I figured out how to destroy and ways to mimic the photos from my parents house. I'm really happy with the way that all came out, because it is a cohesive statement. Having put out records since then makes it even more apparent how hard it is to stumble upon something like that. I don't really feel like every record has to be that, though. You're backing yourself into a corner if you think every record is going to have this catastrophic, amazing, emotional thing tied to it. It just doesn't really work like that. You can't wait around for that sort of thing.

Andrew: Yeah, I'm so glad you say that. I think if more people were being honest, the press releases would be a hell of a lot less interesting. I think it would be something to the effect of, “I was fucking around with my delay pedal one night, and here's what happened to come out…this is the product.” And we feel this… I've talked about this with a couple other people, actually, in this space. There's some kind of insecurity there, I think, where you feel like “this sounds like it should be so easy to make.” You've got to justify its existence with some kind of grand narrative or story. And, I don't think it's like that.

Scott: The relation to film scoring - it's adjacent to that. People think a film score, as amazing as it is, it's got this thing tied to it that just elevates it. “I need to have something to elevate it, because having it stand on its own is a little scary.”

Andrew: Yeah, and even saying that - “I scored a film” - that just sounds so fancy.

Scott: Everyone that makes music like us is always like, “Oh, I'd love to do a film score.” That's the thing you hear everyone say, which is not false. Everyone would love to do that.

Andrew: That's like the ambient dream, yeah, to score films. And I think too, what makes me think about it a lot is that background that I have. We were talking about playing bass guitar before, and history performing with bands, and there's that comfort factor of having the instrument in front of me. People can see what I'm playing. They see my fingers moving and can make the correlation, the connection with the sounds. Whereas, nowadays, I'm hunched over a laptop and an Octatrack or whatever, and it's not as easily apparent for people to see what's happening there, like the skill that goes into preparing some of those samples and stuff like that.

Scott: Yeah. When I first started, I was playing live with a laptop, and I had a lot of other little like circuit-bent gadgets and other shit. And playing shows like that - I'm sure it was everywhere in the early 2000s, but nobody really knew what to make of that sort of thing. People were either like, “what the fuck is this?” Or “this is the greatest thing I've ever seen.” It was polar reactions every time, which is fine. That's almost what you want it to be, but it was definitely weird. Now, people know DJs and people know laptop artists and everything, but there was a time when people just did not know what the fuck you were doing up there.

Andrew: Right, exactly. I have this sticky note of ideas of articles I want to write, or stuff I want to do with Sound Methods and topics to address, and one of them is just going through: “what are the worst shows you've ever played? What are the worst experiences you've had presenting ambient music to people? How was it received? What was the setting like? And what did you learn from it?”

Scott: The worst one immediately comes to mind. It was in that period of time. I was backstage, partaking a little too hard in some substances, and before I know it, it was time for me to go on. I hadn't even turned the fucking computer on yet, and I had the startup music play over the PA, the Windows startup music. At that point, you just have to say, “fuck it.”

Andrew: That's when you need an iPad running Paul Stretch to slow it down 800 times.

Scott: If I had my wits about me, I could have figured something out, but knowing that I had to turn the computer on and just literally wait…not that I was playing a fucking stadium or anything. There's not a lot of people there anyway, but it's still a little funny.

Andrew: I think back to those experiences though, and yeah…we've played some horrible shows: through one PA speaker because one of them blew out, so we had to play the show in mono. Or there's one other person there, the room's totally empty, and you can hear the AC system over top of your music and all this stuff. Yeah, there's plenty of horror stories to share. But those are actually, to me, some of the most fun things in retrospect to think back on, because that truly is where you learn what works and what doesn't. And I think the live presentation of ambient music is where you really start to appreciate how hard it is to just sit with a texture, or sit with a drone or whatever that you've just crafted, and just let that be.

Going back to the point about narratives and feeling the need to justify the music in some way, or attach some deeper meaning to it, sometimes there is something meditative and worthwhile about just sitting with a sound for a long time, and just letting it happen and be what it is, and just accepting the fact that some things are not going to go right every now and then.

Those experiences to me are so fun to think back on.

Scott: Yeah, I've had many of them. Not just in the ambient world, just in band world in general.

Andrew: Yeah. I'd love to hear more about what you just brought up there. The scene years ago in New Orleans might have been a lot different than what it looks like now. Are you connected to it in any way now? Are you still playing live? What kind of community or scene exists there now? I just like hearing people's perspectives.

Scott: I’m not really playing live too much, anymore. I'm of the mindset that if the right scenario or the right show came along, then I would put something together. I played in bands so many years, and sat in so many bars waiting to play and just killing time in a bar - I'm not a big bar guy, anyway - so for me to go pack my set up and go out and play music somewhere, it would have to be the right scenario for the right people.

But yeah, there's not a whole lot going on here in that world. There are some people making amazing music. My friend Melissa makes music as MJ Guider; she's on Kranky. And of course, there's the Belong guys; one of which does Second Woman with the current Telefon Tel Aviv guy, Josh Eustis. So there's some people here scattered about like that.

I'm also not 20 years old, so I'm not in the thick of what the underground scene is or whatever.

Andrew: Yeah. I'm with you. Those years are starting to slip away from me, I can tell. With kids now and everything, my outlook has changed quite a bit, but it's always interesting for me to hear from people in different parts of the country or even parts of the globe, how their surroundings affect what they do or how closely connected they are with it. Especially in the post-pandemic era, I can just sense a lot of change here in Philly. If I were to go try to set up a show tomorrow, I don't even know who I would contact…I used to just, at the drop of a dime, [be able to] play a show in five or six different places. So much has changed. It feels like starting over in a lot of ways.

Scott: That's why I don't want to say I’ve given up on it, but I feel like I did it so much that it's out of my system. I'm not yearning to go play live shows. The music too…it requires a special environment. It just does. I don't want to go play at a dive bar where people are just there to drink and hang out and have a good time. It could go well, but [I don’t want to] lug my things out. Of course now, these days, I don't really have a lot of gear to lug out. I'm on the iPad train like you.

Andrew: I love it. So, it wouldn't be an interview with you if I didn't bring up Onde Magnétique, the, cassette synths that you've produced in years past. I was listening to a podcast interview that you did previously, I forget which…maybe it was Podular Modcast or something else, but I think you got into a little bit of your history with circuit-bending and other kinds of “toy instruments,” quote unquote. I'd love to hear you tell that story again, if you don't mind. How did you get into this space with the OM-1 and how did that come about? It's so cool. And I didn't even realize until pretty late in the game that you were the guy behind all that.

Scott: Yeah, I guess around the time that I started getting into the more electronic stuff like Aphex Twin and Boards of Canada in the late nineties, at some point I had a ‘69 Jazz Bass and I was like, “I'm not really trying to make this kind of music anymore. I want to do something different.” So I sold it and bought a computer and had Acid Pro on it, which was like a loop program.

And from there I was like, “I want to start sampling from records, and I need other things to use as sample fodder.” That was early internet days, and there were some people who were doing the circuit-bending thing and it was just super intriguing to me. I never really made noise music, per se, but to be able to modify these things and sample them and then use them in more musical contexts was just a quick route to a more interesting, or personal, aesthetic.

I wasn't really using traditional synths a whole lot at first. I had one synth, the Moog MG-1, which was like the Radio Shack Moog. I learned how to do some modifications to that thing, and I had an old Roland drum machine that I modified to add trigger outputs to it, and things like that. It just snowballed over the years of tinkering and building little things for myself, but also for other people at that time. I built a little thing for Mark Mothersbaugh [of Devo] and a couple other people. I sold them on eBay and since it was early internet days, it wasn't really like you had that much of a reach. I stopped doing that for a while, I moved, and I got rid of a lot of the little trinkets and shit that I had just laying around, because you know, when you move, that's what you do.

And I guess sometime in the late 2000s I got back into it, and got back into the tinkering and building things. I've always been obsessed with cassettes since I was a kid, so that [OM-1] became this little thing that I made and was screwing around with. I posted on Instagram and people liked it, so I ran with it…here we are today. It's just always been something that I wanted to pursue, like actually making instruments and things. I have other instruments in the works; hopefully they'll be out this year.

Andrew: Yeah, I was going to ask if you have any plans to further that.

Scott: I do. I’m working on a little ecosystem of three or four devices that can all work in tandem, almost like taking a lot of the techniques that I've learned in modular and just breaking them out into smaller, affordable, easy to use, fun little things that you can actually use in music. They're not just toys, you can actually make music with them. So that's the plan, and that's what I'm working on right now.

Andrew: Cool. Looking forward to seeing that. And I guess on a similar topic to what you just mentioned, the modular and learnings that you took away from that: I had a period, too, where I dabbled with modular synthesis and I think I learned a lot from that. Honestly, if I still had a little more free time available, I'd probably still be dabbling with it a little bit, but I ended up getting rid of a lot of it. I do regret that a little bit. But I'd love to hear how you got into it to begin with. How were you introduced to modular synthesis, and is it still a big part of what you're doing today? You hinted at the iPad there, but yeah.

Scott: Yeah. I can't remember exactly how I got into it, but think I wanted to just make a little basic drum machine that had some interesting pattern generation built into it. I got a little case and a few modules and did what I set out to do with that.

It’s super fun because when you've been in the game so long, you get ideas of “what if I did this, and put this with that, and triggered this from that?” Modular lets you do all that stuff, and actually carry out all the ideas. A lot of that stuff I had started to tinker with when I was doing the circuit bending and making my own devices, where I would put a trigger input on something and add a trigger output to another thing. Having those two pieces of gear speak to each other is just like a revelation when you've never experienced that before. Even MIDI. The first time I hooked up MIDI to a Juno and had it play, it was magical. The aspect of speaking between different devices is what was alluring about modular, and I went down the rabbit hole a little bit. I can't say that I got as crazy as a lot of people do - I had maybe a 208 HP case; that was probably the biggest case I ever had. And at this point I just have a little small case based around the ER-301 sound computer, which is basically a “modular in a module.”

I think the reason why I like the iPad stuff so much is because it's like that. It's almost just like a little modular synth that you can do all these things with, like polyphony, which is hard to do in the modular world. And so, when you're dealing with something like the iPad, it's so easy to just have polyphonic sample players or synths or whatever. The modular - I still love it, but like you said, it just takes a lot of startup time, and the less time you have, the more you just want to sit down and start right away. You don't want to patch everything. I still have a lot of respect for people that do that, and maybe I'll build my system up again at some point. I still have a good bit of modular sitting around, but, at this point, it's just like, "I can plug that Digitakt right into the iPad, and it's “what can't I do?” It's just magic.

Andrew: Yeah, I know, it's the best. I think I've got my setup time to 10 seconds. I can sit down at my desk, I've got everything - my interface is ready to go here, I just plug the cable into the iPad and I'm up and running. So after that, it's hard to go back to finding an hour of time just to patch a system, get it ready to go, and then you can hit record. It’s just a different mindset.

Scott: I also find that a lot of the people developing for iPad remind me of what the eurorack people were doing maybe six or seven years ago, where it just felt like all this new stuff; all this crazy stuff that was so creative and so new. Not to say that people aren't still putting great things out, but it does seem like the Eurorack world has cooled off a little bit in terms of technological advancements. But you see a lot of stuff on the iPad where it's not that it's easier to build those things, but it's easier to put them out, because it's not a piece of hardware, right? As someone who does make hardware, there's a lot of pitfalls there. So if you're putting out a piece of software, it's probably a little smoother to get your idea out there.

I think a lot of people have just dove into that world, and there's so much good stuff. Plus the expense too…coming from the modular world, at this point, whenever I see an iPad app that I like, I just buy it. I could buy 15 of them and I still would not be at what I've paid for one module yet.

Andrew: Yeah. Just for an external interface module. I know, it's crazy. And it's such a good point: I feel like there's a very modular type of spirit to the iPad, anyway. You open it up and you open a session in AUM, or you open a session in Loopy Pro, and you can literally build your system there. That's the equivalent for me, at this point. Now I'm just paying for $5 apps rather than $150 modules - or even more, in a lot of cases.

Yeah, it's like that same spirit, I think. Just a much more efficient delivery.

Scott: It really is. And I'm sure you’re the same way, but I'm just such an evangelist of the iPad ecosystem now. People are asking me how to do certain things on the modular or whatever. I'm just like, “just get an iPad.”

Andrew: Yeah, exactly. I say that all the time. In fact, my friend Dave, he jokes with me all the time: “you're like the Michael Jordan of iPad, man. You just own that thing.” I'm glad to play that role. I wish Tim Cook would send me a couple of commission checks every time I got someone to buy one, but maybe we'll get there someday.

And honestly, that's the reason why I wanted to start Sound Methods in the first place. I think there's so much potential there that it would be criminal to hold that information back. Might as well let people in.

Scott: It seems like people are responding to it. It seems like there's a lot of people interested in that.

The hybrid setup, that's where I'm at. It just gives you anything you could possibly want, whereas in a strictly eurorack environment, you have to make some concessions, polyphony being one…not that there's not ways to do that. But, obviously, budget is another huge aspect of the eurorack thing.

Andrew: Yeah, it's definitely an investment. It holds its value, but it's a steep entry price.

Why don't I look to the future now. You mentioned some stuff that you're doing with Onde Magnétique; you've got some work going on there with hardware that you're building. What's going on with your music? What do you see happening next with your work and where is it going?

Scott: I'm working on something now. At this point, I'm in that preliminary phase where I'm just going through making samples, making patches, experimenting with different processes and techniques and things like that. I'm pretty close to starting the actual recording process. It feels like it's been a long time since I've put out a record, so it's probably something I should focus on.

Andrew: Actually, it hasn't been, though. I think it's only been two years, which is actually pretty normal…but in this day and age, everything feels like a compressed timeline.

Scott: Yeah, I don't feel too much pressure. I just don't want too much time to go by. And then people have completely forgotten about me. [laughs] No one remembers that I made music.

Andrew: It's hard, man. I know. What was released six months ago already feels like ancient history.

Scott: Yeah. Of course, too, I'm also in a place which - it seems like maybe you've talked a little bit about this, too - I'm just trying to like find the next thing, and not rely on old techniques. I’m just trying to find something that still relates to everything that I've done prior, but is adding something, or is a step in another direction. I think I've found that, and like I said, I'm just building the building blocks that will become the record at this point.

Andrew: Yeah. That's great to hear. I'm super looking forward to that. And on that topic, it just reminded me - I think you're on the lines forum. For people listening here, it's a forum that I think was initially started to cater to the Monome devices as a user group, more or less, but it's grown to encompass a little more than that. It's just a general electronic, experimental, ambient world. A great community. But there's a fantastic thread on there about “post ambient” music, and I was reading through that the other day because I got a notification that someone liked a post I had made in there.

But it's interesting to read through that thread, and to your point, figure out what the next steps are from these pandemic years of super introspective, quiet, background music…how do you reclaim the genre, more or less, or put your stamp on it? It's really tough to do.

Scott: I think a big part of it for me, too, is that with Instagram and YouTube and everything, everyone’s sharing their processes. It makes everything easier to do, which is good in some aspects and not good in other aspects…but it makes it harder to break into the non-ordinary parts of those genres. I guess that's why I've not really jumped to put anything out. I'm not saying I'm gonna write the next masterpiece, but I just want it to add something to the conversation rather than just be another ambient record, because there's so many now. There's so many good ones, mind you, but there are so many.

I sound like a fucking old dude, but starting out in the early 2000s, nobody knew how any of this shit was getting made. Nobody understood how Boards of Canada or Aphex Twin were doing what they were doing; it was a mystery, so you would try to figure it out. But in that figuring out, you would figure out your own thing, because obviously you're not going to figure out exactly what they did. Whereas now, there's so many tutorials out there - and I watch those tutorials, I'm not saying that's bad at all - it just makes it easier to start, but more difficult to find your voice. You've been given the tools more than a lot of people in the past were, I think.

Andrew: Yeah, exactly. I think about that all the time, actually. I'm really glad you brought that up because I…with what I do on Substack, I'm trying to do that. I'm trying to give people the starting point, the initial connections to then figure out your statement that you want to make, or figure out your voice with the equipment that I'm using. But yeah, there is a fine balance to be struck. I do miss that mystery a little bit, and the challenge of being motivated to figure out what the hell is going on in this amazing piece.

Scott: Just the surprise of hearing something, and not automatically being like, “Oh, no, it's this app, or this module,” or something else. Which, I understand that not everyone has the frame of reference to know those processes or whatever, but when you've been in it for a while, I guess it becomes more apparent.

Andrew: Yeah. And I'll sound like the old person here, too, at this point. A little bit of my life was pre-internet and pre-computer, and that wasn't a part of my early childhood and even through high school, really. That was not a part of everyday life, living online or on social media and stuff like that. And it wasn't until I had graduated from college that smartphones and social media became a legitimately big, everyday thing, and then it felt so invasive at that point. You have to let people into your life.

But I bring all that up because I can remember a time when I was learning to play bass guitar, and if I heard a song that I liked, I had to sit down - I sound like that old guy yelling, “I had to walk uphill both ways in the snow!” - but I had to sit down at my parents’ stereo and manually rewind the tape, or the CD, and try to learn the part in real time, because there wasn't software to slow it down or anything like that. And that taught me so much…there was such value in having to go through that little bit of work to find my voice or find how things work.

I'm totally just ranting.

Scott: Yeah, in the early days of electronic music, [artists] were using things in ways that they weren't intended to be used. And now everything is developed with intentions that you use them in exactly the way that they were intended. And that's great, but a lot of the people who we love, who started these genres, invented them because they were pushing gear to do things that it wasn't really designed to do.

But it's hard to have these conversations, because I'm not just on one side of it. At the same time, I love all the new gear. I love all the technology, I love watching tutorials. I just think it's harder to break in to find your personal voice than it was before.

Andrew: Yes. It's far easier these days to mimic rather than to innovate. And part of that is just sheer timing: there's already been so much done, that what more could be done?

But I think back to that [Brian] Eno quote…I forget exactly what he said, but he was like, “the undesirable aspects of technology in years past will become desirable in the future.” The tape will break up, or 12 bit sample rates on samplers…there are plugins to replicate that shit exactly now, to dial in the sound of a broken tape deck if you want to, in a pristine DAW environment with no pushing of the limits.

“Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit - all of these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided. It’s the sound of failure: so much modern art is the sound of things going out of control, of a medium pushing to its limits and breaking apart. The distorted guitar sound is the sound of something too loud for the medium supposed to carry it. The blues singer with the cracked voice is the sound of an emotional cry too powerful for the throat that releases it. The excitement of grainy film, of bleached-out black and white, is the excitement of witnessing events too momentous for the medium assigned to record them.”

Scott: I feel the same way about when I studied graphic design. I was in school when they were just starting to use computers a lot, so I think for me, in music and design or whatever else it is, I think it's just important to learn older techniques, or older theory and modes of art creation, because those are universal and those can be applied throughout time. The gear will come and go, but if you just have that base of a theoretical place to start from, or specific techniques that were used, [you have a starting point]. A lot of the tape techniques that I've learned over the years, I might not necessarily use them. I might use a tape emulation app, but I know what it's supposed to sound like. I know where I'm going or what the outcome should be if I want it to sound like what the real thing is.

Andrew: Exactly. That's the exact example I was going to bring up, too. I have a shoebox in my closet over here in the studio that's filled with old handheld tape recorders. There's a Sony model - the “TC” something or other, I can't remember what it's called. I've bought probably 20 of those on eBay over the years, just because they keep breaking and I keep rebuying them to get the sound again. I know that sound so well, and I've used it on earlier albums.

Now, if I want to get that sound, I know it well enough that I can save myself a little bit of time by loading up a plugin. I've got a setting that I know is an exact replication of that.

Scott: The Marantz stereo deck - the PMD 430 or whatever it is - I built a little preset in Chow Tape to sound exactly like that. There’s so many controls in that little app that you can do whatever you want with it, and tweak it to the perfect point where you can make it sound like a destroyed Marantz, or a pristine one, or whatever you want it to sound like.

Andrew: Yeah, it’s fantastic.

Scott: Just having that frame of reference, of knowing what you want to get out of it…there's something to be said for not knowing anything about it, just experimenting blindly, too. When I was a kid just buying these little toys and little synths or whatever, I knew nothing about it. But I felt like that was the most fun I've ever had with music; the complete lack of knowing.

So, basically, I'm just gonna contradict everything I've said on both sides of the argument.

Andrew: It's such a balance. Like you said before, there's no sense in gatekeeping any of it, but at the same time, it's important to recognize there is some value in figuring this stuff out for yourself. Piece the two together however, you want to do what you want. But yeah, there's a balance I think, for sure.

This has been a really fun conversation. I really enjoyed hearing your perspective on all this, and definitely look forward to this new music that you're about to embark on. Looking forward to the finished product, whenever that's ready…take your time. We'll be waiting.

Scott: Thanks for having me.