A few months ago, in the preamble to my interview with the developer of Samplr, Marcos Alonso, I noted that “only a few instruments” have ever offered me such an incredible degree of instant, on-the-spot inspiration as that one did. One of the “few others” that I was referring to was Borderlands Granular.

I think the best summary of Borderlands that I’ve ever read was this statement offered by Peter Kirn in CDM several years ago:

If you bought an iPad just to run this app and nothing else, you might be perfectly happy.

I couldn’t agree more, which is why I'm thrilled to welcome the developer of Borderlands, Chris Carlson, to Sound Methods.

First, a little about Chris:

Chris Carlson is a software developer and musician based in Richmond, VA. He is the creator of Borderlands Granular, a visual music app designed for exploring sound with granular synthesis. Over the course of its nearly twelve years in the App Store, Borderlands has found its way into studio recordings, film scores, live performances, educational workshops, and field recording expeditions. It has developed a worldwide community of users including artists such as Fennesz, Laurel Halo, King Britt, Arovane, and Pan American. The app was honored with an Award of Distinction in Digital Music and Sound Art in the 2013 Prix Ars Electronica and has been recognized and presented by the ZKM Center for Art and Media and Sónar Festival. Borderlands has been called "a reason to own an iPad" by Peter Kirn of Create Digital Music.

Chris is also the Director of Creative Technology for Art Processors, an experiential design and technology company based in the US and Australia. He works closely with a multidisciplinary team of designers, content strategists, engineers, and producers to create museum exhibits that foster learning, connection, creative expression, and delight.

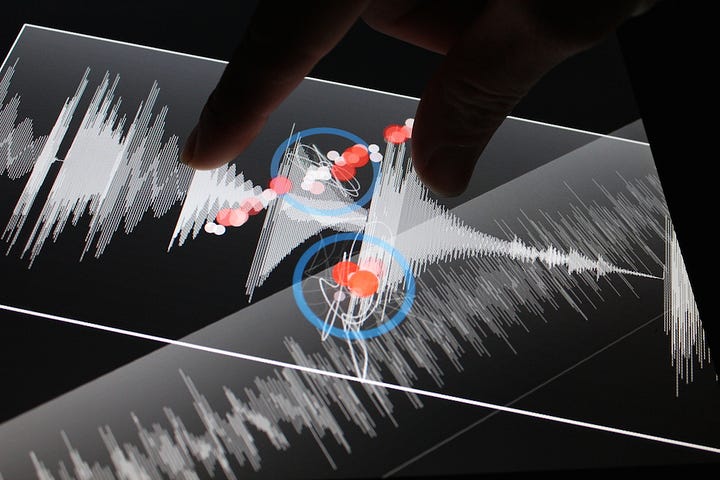

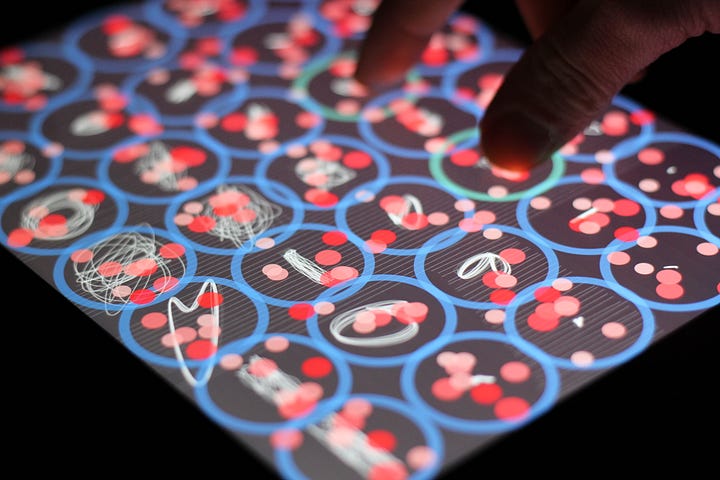

I knew that as soon as I started this podcast series, I wanted to talk to Chris and pick his brain on how Borderlands came to be and where it's headed. It's been instrumental in my own music over the years, and I’ve lost count of the number of song ideas I’ve started with those familiar red and blue grain clouds hovering over my prepared samples.

Borderlands has become the de facto standard in granular synthesis in the mobile music world over the last 12 years since it was first introduced in 2012. Although there have been countless takes on granular synthesis over the years, I struggle to think of any that are as enjoyable, inviting, and downright beautiful as this.

We had a great conversation on all things Borderlands, of course, and I think anyone who’s a fan of the app will be really excited to hear about everything Chris is working on right now (iPhone compatibility, you say?)…but we also touched on Chris’s personal life, musical background, and work as a designer of software and experiences for cultural institutions across the country.

Here’s my interview with Chris Carlson. I spoke with him over videoconference on Thursday, April 25 from his home in Richmond, VA. Visit http://www.borderlands-granular.com/app/ to read more about the app, and be sure to download it on the App Store through the link there.

Transcript

Sound Methods 008 - Chris Carlson

CCRMA and early history of Borderlands

Andrew: Chris Carlson, thanks so much for being here on Sound Methods. Really appreciate you taking the time to join me today.

Chris: Yeah, my pleasure.

Andrew: So, this was a long time coming. I had you in mind when I was first starting to plan out this podcast, what I wanted it to be, and who I wanted to talk to. And actually, I put out this feeler for who people would want to hear in discussion, and your name came up multiple times. I think you've got a very solid fan base with the Borderlands app, so I'm glad that this is happening.

And speaking of Borderlands: if I think back to when I first started making music on the iPad - that was probably around 10 years ago - I had this horrible, slow, first-gen iPad mini I was using at the time. I think if Samplr was the first app I downloaded, Borderlands was probably the second, and I did it blindly. I didn't even have a full understanding of what it was; I was just kind of reading what people were using at the time, and everyone kept mentioning Borderlands.

Now, it's one of those “Mount Rushmore” apps. I think people talk about the apps that they use when they get into the iPad, and that's inevitably up there as one of the first things mentioned. So, as the gateway that it is into iPad music-making, I would love to hear you take us back to that time in your life. What is the origin story behind the app? What motivated you to start this? What was the context behind its creation? Where did the name come from, was a question that I wanted to hear about…but yeah, I’d just love to hear the origin story here. How did Borderlands come to be?

Chris: That is a big question. Many avenues into that one. I think I'll start around the time that the idea came together and what led to that, and then maybe we can go back further later.

But first of all, it's great to hear that people are excited about it, and thank you for the kind words about the app in general. It's always amazing to hear that, because for me, it's this thing I work on at night in my spare time, and I don't often meet a lot of people who use it, so it's very much in this nebulous internet world. I interact with people on Instagram and stuff, but it's really great to hear because for me, it still feels like this strange, half-broken thing that I'm working on. The one in the [App] Store is not broken, but the one I'm working on here is.

Andrew: The imposter syndrome already coming out.

Chris: Yeah, let's just get that out of the way right at the beginning. That is kind of like the theme of the story, though, of the app. The app started as a side project - I'm sorry, it is now a side project. It started in graduate school as a class project. I was studying at Stanford University, which has a program called the Center for Computer Research and Music and Acoustics, known as CCRMA [pronounced karma].

It's this amazing facility, kind of a mixture of musicians, students, and engineers, super into interdisciplinary [studies]. It’s a really amazing place to study. I was doing a master's degree there. I went there because I was interested in learning more about how to make new musical interfaces, and didn't have a lot of programming experience beforehand. I'd just come from a job in a completely different industry doing little bits of programming, but that was something I always felt really insecure about…you'll probably hear that come up several times in the story. But I had finished my first year there, and there's this one class that I knew I should probably take, but I kind of put off taking because it was primarily focused on C++ and I thought, “you know what? I'm not a programmer like that.” I'd done some creative coding and done some Max and been really interested in it, but I was nervous that it would just be this terrible train wreck trying to figure out C++ and develop a final project in that class.

We went through this sequence of steps. It was very project-based: the first exercise, is printing out a waveform using a C++ program. The second exercise is learning about OpenGL, and drawing a spectrogram with OpenGL and building an application that does that; you had to figure out how you wanted to make it work yourself. The third one was about learning how to deal with MIDI input. And then the last piece was a final project that you had 11 weeks or so to work on - no, sorry, 5 weeks. I think of 11 as a significant number for Borderlands just because it was November when I got started on it, so when I think back to that date, it was 2011…that's why that number is popping in my brain.

So the assignment for that project is basically, “okay, now you know some C++ and know how to make some visuals. Make an instrument and something you can actually do a performance on. It doesn't have to work more than a few minutes, but it has to be something you can make some music with.” I had always wanted to do something with granular synthesis. I really liked working with samples in my own music, and having just learned how to do some things in OpenGL, I was like, “all right, I'll try to make a visual interface for granular synthesis.”

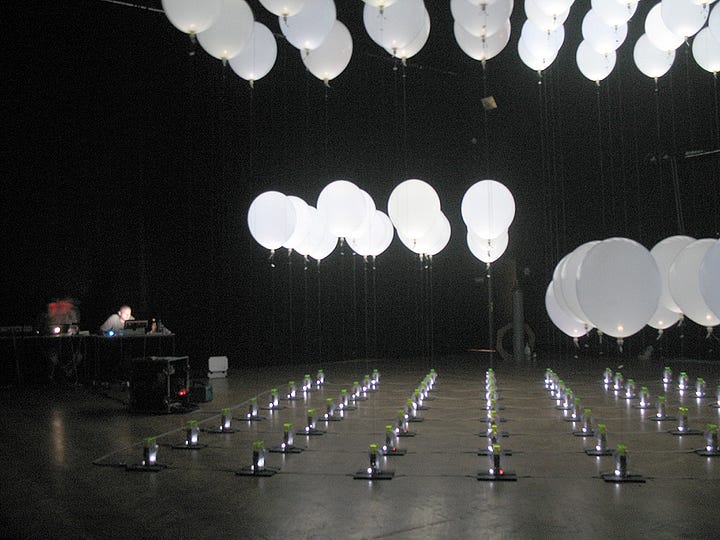

And I don't know, I might get into too many details, but some of the sketches I sent along, it started with this idea that was inspired by the visual of this piece by Robert Henke and Christopher Bauder called Atom, which is just a bunch of balloons on tethers that are lit up inside.

And I thought, “Man, that's such a cool visual image for granular synthesis.” I started thinking about [how] OpenGL is all 3D-based. “I need to make something 3D and it needs to have shapes…I can send scanners over this 3D terrain, and it somehow samples grains of sound based on the terrain shape.”

Quickly, I realized this [was] going to be really difficult to do an intuitive performance with, and also really hard to implement for someone who's only got a few weeks of C++ programming and had my own prior conceptions of what software was like.

So I collapsed it into the 2D realm and I started thinking about, “all right, what can I do with the X and Y axis? Like the [Korg] Kaoss Pad or Ableton with the XY parameter manipulation.” That's when, after iterating a bunch, I landed on this idea of: “let's put the sounds on the screen and just sample them with the grains; little dots that just pull samples out. And since the sounds are there, I can grab multiple sounds at the same time. That sounds pretty straightforward. Granular synthesis is basically just a bunch of glorified sample players that are fading in and out over time.”

So I set to work on that, and in that five to six week period, the first desktop prototype [was made], which you launched from the command line.

It came into being, and the core of that is still there. There’s code that was written during that period that's still in the app today. The kernel of the app is these granular synthesis players, and I've added on to it in so many different ways, but at its core, what you could do in that original version was like: you launch the app from the command line. It looked for a specific directory and loaded whatever sounds and were in that directory. You had to use a mouse and keyboard; all the parameter changes were done with keyboard shortcuts - click on a cloud and touch a key, and then enter a numerical value. And that was kind of the extent of it. It couldn't save anything, it couldn't load extra stuff. You just had to start from scratch. That's where it initially began.

[Above: the first recording ever made with Borderlands, from November 2011]

Then, a follow-on course to that one happened because it was 2011. This was when the iPad 1 was just wrapping up its initial run and iPad 2 came out in the spring of that year. I took this class in the fall of that year - the next class was one on mobile music. That was the focus; CCRMA is always trying to work with the latest technologies, and that happened to be the coolest thing. So I took this class and I was like, “is it really going to be that cool on an iPad? It's probably not going to be worth it. I'll just keep it on the desktop.” But I worked to port it over for that final project, and the moment when I first touched one of these grains and showed it - I remember standing and showing it to my classmates at the time and being like, “look, it's starting to work!” And people gathered. I was like, “this feels really special. There's something happening with this that I need to pursue and keep working on.” So that was the moment where…that made me want to push forward and try to get it out in the App Store.

[Above: the first sounds made on the mobile version of Borderlands, from February 2012]

Design and aesthetic of the app

Andrew: It's so interesting to think about it in desktop format. I can't even conceptualize that, just because I'm so familiar with it [on iPad]. I use it all the time in my own music, and I'm having a hard time even imagining what that experience would be like on a desktop because it does feel so ingrained in my brain - no pun intended there. The experience and the feel of it, the touch, the gestures…all of that is just fantastic.

And that brings me to a point that just popped in my head here: thinking about that - the aesthetics of it, the look, the feel, everything - did you have any assistance when you were thinking through the graphic interface and the visualizations? Is that at all in your realm of expertise, or is that kind of just something that you felt out over time? Because I think it's a big part of the experience of the app: seeing the grains there and the visualization of it is really key to experiencing it.

Chris: So the short answer is no, I did not have much help. But it's slightly more complicated, in that some of those icons that go around the perimeter - the UI buttons - those are iOS.

I think of the app in two sections: the core of it, which is C++ and custom code, and everything that you see on screen that you're touching that's not a button or a table or a UI. Then the perimeter stuff is iOS UI kit specific stuff that I pulled in just because that's the easiest way to work in that context - on the iPad. I didn't have any experience with Photoshop or Illustrator at the time, and so a friend of mine named Ben Nicholson basically took my sketches and produced the first run of those icons for me. Then he handed off the file - an illustrator file - to me. After 2013 or so, I was just using that to make my own icons and figure that out.

In terms of the core of the app, though: the blue circle, the grain clouds which are defined by those blue circles and the collections of dots and pulsing grains that are associated with them…and there's the lissajou plot that happens in the center, which shows the harmonic content and spatial content of whatever's playing back at a given time…all that is just stuff that I iterated on over time as I was pushing into the app. Because it was on a glass screen, I wanted it to feel as physical as possible, to the point where it feels almost like when you're interacting with the app, the glass is sort of disappearing and you're touching the sound directly. And so, to accomplish that, I felt like adding visual feedback and subtle cues within the app would help it feel more alive, more organic…even down to the point of adding some physics to it when you drag things around, making it so that it's not so abrupt. It feels like they're just more fluid.

And that just came through tons of time trying stuff, experimenting, adding things in there. There's tons of little bits of code peppered throughout the app that are just based on what felt good in the moment, and how it looked. The simplicity of it is due to the fact that I just didn't how to do more complicated stuff graphically, so I was just like, “it has to be 2D. It's going to be flat colors with transparency,” and that's basically it. I was really fortunate that I had no idea how to do fancy shader effects or anything at the time, because it kept it from being too overproduced, you know?

Andrew: Yeah, I totally agree. It's the right amount of feedback, the right amount of stuff happening. I feel like anything more would maybe feel convoluted or difficult to navigate.

And it's also funny, too, I mean…you mentioned making music on an iPad at that point in time. It’s surprising to me to hear that the program you were a part of was already thinking about it at that point, because I don't think it really caught on until a couple of years later, at least from what I can tell and just purely anecdotally speaking. That seems to be pretty far ahead of time in terms of thinking about the [iPadOS] platform as a legitimate music-making tool. I think back to that point of iPad history, and the things were very clunky. I just associate it with…they were basically glorified internet browsing tools. I don't think they were really doing anything substantial at that point.

Chris: It was interesting. I remember being really surprised and skeptical about it when the iPad first came out in 2010, or whenever it was, and didn't really start to grasp it until I saw the way people were using it and starting to do musical apps for it.

But the reason that CCRMA was thinking about that was largely because one of the faculty there was Ge Wang. He founded the company Smule and developed the Ocarina app on the iPhone, so there was a mobile music class there for a couple years going on because of the iPhone.

Once the iPad hit, it was an extension of that. Fortunately, the way Apple structured things, the process of developing an app was essentially the same [on iPad and iPhone], just different layouts. But yeah, it was pure coincidence that my timing at this particular program happened to line up exactly with the iPad becoming capable of running something like Borderlands. If I had been there a year earlier, Borderlands probably wouldn't exist. I doubt I would have had the time or felt like it was possible to even try for that.

Origin of the name “Borderlands”

Andrew: Serendipity, man. I love that. I'm glad it worked out, just selfishly speaking…

So I'll just ask the question: where did the Borderlands name come from?

Chris: So, this was back when I was working on the desktop version - I had to present it for the final project presentations, and I wanted to have a name for it. The short answer is that it came from a Tim Hecker track. I basically was just like, “all right, let me look through my Tim Hecker records and see which one is the track that feels appropriate for this app.” And I found Borderlands.

That track has these beautiful, shimmering pianos in it. It's on the record An Imaginary Country. That particular record is not actually my favorite of his, but I do like that track a lot, and the name just kind of popped out at me when I was looking at it. I remember thinking, “this is perfect. It fits the idea of the landscape - a kind of sonic landscape with the clouds, [and] sampling from the landscape.”

I remember I showed up for the presentation and I mentioned all my classmates about it and they were like, “you know there's a video game called Borderlands, right?” I was like, “well, it's probably not a big deal. I don't really care, I don't play that video game and I’ve never heard of it before. It's probably not something I need to worry about.” And then the app got some press from Create Digital Music - well, it was just the desktop version. I had posted a video on Vimeo of the desktop version, and Richard Devine picked it up because I think he was just scrubbing Vimeo for new sound stuff for some reason, and he tweeted about it and that led to a CDM article from Create Digital Music.

And so, once that happened, I was like, “well, the name is stuck now. I can't change it because everyone knows that this thing might be coming.” Peter Kirn posted an article on the iPad prototype once I had finished that up, as well. It was probably six months before the first version actually came out in the store.

When it came time to submit the app, Borderlands 2, the video game, was coming out. I was trying to get it into the store and I figured it probably wouldn't be a big deal because it was listed as a music app - the description was very clearly not a first person shooter game - but it got rejected. I found out about the first rejection on our drive to Portland when we were moving there, and then I had to scramble to figure out how to get around it. I filed [an appeal], submitted again, [and was] rejected the second time. I was trying to think of, “what can I do to change the name? I have to keep Borderlands. Maybe if I just add a word to it…” I almost changed it to another Tim Hecker track and then I was like, “no, it doesn't feel right. It has to be this name.” So I just appended “Granular” to it and filed an appeal with Apple where I said, “I'm not trying to infringe on copyright. This is a music app. It's very clearly different in purpose.” There were music releases named Borderlands; there were all other kinds of things out there with the “Borderlands” name not affiliated with the video game in the App Store, and they accepted it. And I hadn't attached any delay to the release, so I was sitting at work one afternoon - it was October 16th, I remember because I sometimes will celebrate the anniversary of this - but in the afternoon at work, I got this email that was like “Hey, your app is released. It's going into the store.” And then minutes later, it was official on the store. So, yeah, it was exciting.

And then all the bug reports came pouring in.

Chris’s musical background and influences

Andrew: That's so funny. Yeah. I'd never heard that story before, so it’s good to get the context.

You mentioned your own music that you make. I wanted to dig into that a little bit and just figure out, what is your musical background? I asked this when I was talking to Marcos about Samplr, too, but both of you guys designed instruments - Borderlands and Samplr, respectively - that just seem so intuitive, and designed as if a musician would have thought of it. It was really interesting to me to hear that Marcos didn't necessarily have a production background. He did it more out of an interest or passion project, [but] when I pick up Borderlands and think about granular synthesis, I'd imagine that a person making an app like that would have to have a background in, and at least some thinking about, an experimental music aesthetic.

I'd love to hear, what is your musical background? What kind of music inspires you? And what were you listening to at that time that informed your work on the app?

Chris: Yeah, that's a great question. I grew up in a pretty musical household, fortunately. My dad loved to sing, my sister also is a singer. She actually went on to train for opera singing, just because she loved it so much. She's not a professional opera singer, but pursued that path as a passion as an adult, which is awesome.

I only have one sibling and then my parents, and I'm sort of the odd person out. I don't know how I found my way into this completely orthogonal set of music interests, but I was always up in my room listening to whatever the alternative rock of the day was. I loved REM in like fourth grade; they were my first “cool” band that I really loved, and then [I got] into Radiohead and Portishead and all that stuff in high school, just super into all that. My family - none of them really understood it, but both of my parents supported both my sister’s and my musical interests.

I'm going way back, but [there are] several important formative memories for me. We spent a lot of time in my grandparents’ houses, and my dad's mother had in her attic…[my grandfather’s] old banjo and a guitar that they had just kept under the bed in the attic, and they'd gotten kind of damaged from heat and other things over the years. But I remember just going up there and spending time pulling out the guitar and the banjo, and just messing with them. And then my other set of grandparents, he was really into tinkering with a Lowrey organ. He had one of those that he had bought, and I only remember him playing “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer” at Christmas time, but I would go and just mess with the different switches and it had all these drum beats in it that you could toggle on and off and stuff.

So, from a very early age, I made a lot of super tactile musical memories and associated them very closely with family connections, and also being by myself a lot, just experimenting with that stuff. That just kept going into adulthood. Through high school, I played guitar and was in high school bands and all that stuff, and I remember discovering effects pedals. I bought a [Boss] DD-5 delay, and the sound that it makes when you twist the knobs - it completely crunches up the sound because it's screwing with the buffer - that was really a revelation, to know that you can mess with time in music. It doesn't just have to be this linear decay of sound.

So, those are all little breadcrumbs that informed my direction over time. I studied physics in college, then realized I didn't want to do that long term and probably should have studied computer science because that's really what I wanted to do. I didn't feel like I was capable of doing it at the time. We didn't have a computer in our house until I was a junior in high school or something, so I just thought, “I don't know anything about programming. It's probably gonna be really hard.” So, that interest in music coupled with the interest in science eventually pointed me in the direction of creative code, and that's how I found out about CCRMA and set my sights on going there for graduate school.

I was making music in my spare time in that period of my life a lot more, and I got a copy of Ableton shortly after finishing up and having my first job. I'd go to work at this job that I was learning a lot at, but was totally not what I wanted to be doing with my life…and then, I’d come home and I would just work in Ableton and mess around and make really strange sounds. I just remember loving so much the flexibility of Ableton, that you could just take any number of effects, throw them on and completely transform a sound - time stretch things, mess around with it - and so I feel like that really instilled in me this belief that there's a lot of possibility in developing interfaces for music, changing sound, and finding new ways to discover new sounds.

And then musically, the type of stuff I was listening to at the time, it was like Tim Hecker and Fennesz. Those are probably the two signposts that really informed my pursuit of doing things with granular synthesis, but [I was] all over the map really in terms of what I liked to listen to. I won't bore you with tons of band names.

Andrew: It's all interesting context to hear. You've brought him up there, Fennesz - I know he is a user of the app, which has got to be really cool.

Chris: Yeah, he's been using it for a while and it was super rewarding to make that connection.

Andrew: You've got a pretty high-powered fan base of users in addition to him. I've seen Richard Devine using it. Uwe Zahn as Arovane, I know he uses it and I think he provided some template sounds or preset sounds in there at some point, but maybe I'm misremembering.

Chris: Nope, that's true.

Collecting feedback from artists

Andrew: I mean, that's gotta be a great feeling though, to see musicians and artists like that really pushing boundaries and using something that you made. I'd be curious to know if you're in contact with any of them, or if any other artists are actively involved in the feedback loop for the app, giving you input and stuff like that. Or is that more of a self-directed development task that you take on yourself?

Chris: A lot of the app’s development is self-directed, largely just due to the time that I have to work on it, and it's hard to establish those regular channels of communication. It was probably 2013 or so - it was pretty early days - when I set up an Instagram account for the app to document progress what was going to become the second version in 2015, and for me, it was just a way to post updates on what I was doing and have a way to hold myself accountable, or have other people see there's progress happening. That first version was admittedly crappy in terms of being able to work with it and import things, and needed a lot of workflow improvements. So [I was] posting updates there, and gradually over time, as the app gained more traction, that became the way in which I could connect with people - artists and others who are using the app. Every once in a while, there'll be a surprise or someone will just send a message out of the blue, and I'm like, “Oh my gosh, this person's messaging me about my app. That's amazing.” And, yeah, with Christian Fennesz, I ended up having an opportunity to connect with him and meet him. I happened to be in Austria and I reached out and managed to get in touch, and we got to have a little visit.

Around that time is when I set up a beta group, and for a while, I just kept it really small to a few close friends and artists who I wanted to distribute pre-release stuff too, but that became a way to push out features to people I knew would be using it and people whose work I really admired, as well, and just kind of see what happened. It's pretty rare that anybody would actually come back with any feedback. “The latest version of your beta release just deleted all my stuff” - [that] happened once, and it was because the person deleted the app. I won't name the person, but they deleted the app because there was a misunderstanding and ended up deleting it…But yeah, I could see that people were installing it and using it.

There's one person Susanne Kirchmayr; she's a performer under the name Electric Indigo. She has been a really great user of the app, and uses it in live performances. She's one of the only people I've seen use some of the more generative functionality of the app, where you can set the clouds to wrap around the screen and use the gravity/accelerometer controls. She uses that in a live context, which is really cool. She often will provide really good feedback whenever we're doing the testing,

But yeah, it's super helpful to be able to connect with people about it, see how people are using it differently, and also see the ways in which people maybe don't think to use it, where I would think, “this is the way you should use this app.” One thing that I do all the time with it, and I don't see as much out in public, is [stacking] all the grains at the center of the grain cloud and not make them randomly distributed; rather, just keep them in the center. I find that allows me to actually dig into the sounds more and probe sounds directly to find interesting moments in the “in between” versus when you have the grains spread all over the screen. I mean, it's scattered visually, but to me, it also feels sonically scattered - which is good for certain things, but that's not the way I would perform with the app, I guess is how I would put it.

But yeah, it's really cool to see how it has gone out there.

Design philosophy

Andrew: Yeah. And speaking of how you use it, I've wondered this myself a lot of times: what kinds of instruments would I compare Borderlands to? I don't have a good comparison point. I've thought about this a lot, and even thinking back to when I first downloaded the app, the only reason I got it was because it came recommended to me and I just did it…whereas I know for sure that, if I want to get a Mini Moog type of app, I can go download the Moog app or something like that. But there's no direct correlation to a hardware instrument that Borderlands would map to.

Maybe I'm just not thinking of one, but was there any specific hardware samplers or synths that you were borrowing ideas from with the feature set? Or was it pretty much an original design? I'd love to hear how you were thinking about it.

Chris: Yeah, that's a really good question. I'm trying to think back to what I was imagining at the time. I wouldn't say there was a specific hardware example of that, partly because granular synthesis has not traditionally been something that's been brought into hardware. There are great examples of that now, like the Tasty Chips one; 1010, I believe, has the Lemondrop. And the Hologram Electronics pedal as well. Many great examples now, but at the time, I don't think I had ever seen anything hardware-based that informed it.

But I will say - and keeping in the realm of hardware for a minute, or just regular instruments - for me, the thing that comes to mind when I think about how I want Borderlands to feel when you're interacting with it is the way it feels to pinch down a guitar string and feel it resonate beneath your finger. Or even having a good subwoofer in the room with you, when you feel that vibration…the experience of holding down a note, but then also adjusting an effects pedal parameter and listening to that process.

I think I sent you one of the diagrams of the early sketches, but this idea I had in mind at the time was this notion of the “feedback loop of interaction,” and for the app to feel really continuous versus discrete. It's not a sampler or a drum machine, where you're tapping on stuff. It should feel like you're touching and sculpting sound. To me, the experience of playing an instrument like a guitar is really relevant to that. Other things that were inspiring me at the time were definitely - I mentioned Ableton and the effects chains in there; I mean, Borderlands has nothing like that in it. You can't rearrange effects or anything, but this process of taking a sound, transforming it beyond all recognition, and then working with what comes out of that is really at the heart of Borderlands, as well. So, the stuff that gets me excited to work on it are the features that will take it to new places, sonically, versus the workflow stuff which is sort of…it's necessary, but it's not what I want to spend my time on. Especially when I have so little time to work on it these days. It's really hard to find the time, even though I wish I could work on it all the time. But what keeps me motivated is the stuff that is about transforming sound and hearing new things come back that surprise you, that you can respond to.

And so this feedback loop idea is about interacting, making the decision, curating the sounds, interacting with them, listening to the result…and then going back and repeating that process. And the goal with the app - with the visual feedback, with the way it's designed, with keeping it an open canvas as much as possible - is to make that feedback loop tighter and tighter to the point where it's just feels like you're fully in sync with the app and the way you would be with playing an instrument that you're comfortable with. That's super hard to do, especially when you have to change parameters and open menus and whatnot. To me, any interfaces that feel like they have some sort of friction, where you're interrupted from that flow state or “the zone…” I'm always looking for those points of friction when I’m experimenting and developing it, and trying to reduce those or eliminate them. That's the hardest part, is sometimes that's not possible and you just have to sort of live with it.

But yeah, the Ableton device chain - the fluidity of that - was really inspiring. And there's also a complete opposite end of the spectrum [with] a series of Max patches called ppooll. It's like a modular sort of system for Max. I love that thing. It's so hard to understand, and visually the UI is…very hard. If you're not coming in with a full knowledge from the manual, or if you're just trying to find your way with it, you feel like you're fighting this thing to get any sound out of it and understand what's going on. And kind of garish; it's got all different primary colors everywhere. But it's one of those things where it looks like it's going to make something amazing that you just don't expect, and I love that. It's something that feels like it's worth wrestling with, because you're gonna you're gonna get to something that you didn't expect coming in.

So yeah, at the time, that was something that fed that feeling of, “okay, computer-based interfaces…there's a lot of possibility to be explored still, with how to control and manipulate and refine sound.”

Andrew: I just want to pull up the app and start using it right now, as I think about it, because one of the [things you said] a little bit earlier - the fact that you can still be surprised by the way that other people are using it, and the way that they come to it, and you don't see people using some of the features that maybe you thought they would use more, like the generative stuff - that, to me, is the sign of a good instrument, where there are so many layers like that to potentially peel back and dig into over time. And even myself, I find it a very friendly app for being exploratory with. There's not a whole lot of text-based labeling around the UI, and it does encourage you to kind of pick it up and play with it, and move your hands around, and start carving the sound.

I love that analogy that you used, or that reference you made, to pinching the guitar string, because I totally resonate with that myself as a guitar player, as a bass player. That's the kind of tactility and physical kind of sculpting, carving sound [I like]…that feel of playing the guitar and then adjusting pedal parameters, for instance, is a good corollary to what you can do in Borderlands, where you're pressing the sound, you're carving it up with your fingers, and that feedback loop that ensues. I really resonate with the way that you described all that, so that's cool to hear you say that because it definitely comes through in the app.

The evolution of the app and development roadmap

And I guess with that in mind, trying to think through the the things that you wish you could have done at the time of development that you couldn't necessarily do back then, is any of that resurfacing all these years later? I'd love to hear what wasn't possible back then that is possible now, and that you're taking steps towards implementing, in the ensuing versions of the app.

Chris: Definitely. Yeah. That is a very good question to think back about…it's interesting, because I do find there are - especially looking back at some of the older material I was trying in earlier sketches and stuff - there are things that appear in those early sketches that I couldn't do at the time, and are still on my to do list. I knew I wanted eventually to get some MIDI control in there. I knew I wanted to do OSC at some point. Those are big ones. MIDI has not yet happened, but I do have some rudimentary OSC control in there…it just depends on where I draw the line for the next version. But, where to start?

Andrew: [laughs] Yeah, I'm asking you to open your roadmap for us to see.

Chris: No, I'm just trying to think if there's anything that, at the time, I was…

Andrew: Yeah, historical context is nice. I don't know. I love hearing about progress and journeys and steps.

Chris: Yeah, and I think I enjoy sharing that too, because I feel like the story of this app has been a story of learning it as I go. And I feel like these days, I'm constantly battling my past self, “late night Chris” from 2014 making terrible decisions that were getting me closer to the finish line, but now I have to undo a bunch of that to get to the next thing. For me, knowing that people I admire - hearing from them that they don't have it all figured out, is sometimes really encouraging. Talking to Marcos [Alonso]…I know that in our text thread [with Chris, Marcos, and Fugue Machine developer Alex Randon] we can be like, “Oh, man, what's up with this thing? I have no idea how to solve this problem.” And it's “yeah, I'm not sure either, but let's figure it out.”

So, thinking back to the first version, I think if I wish I could change anything about it, it would be just giving myself some knowledge of how to set up some of the architecture of the app to handle some bigger scenarios. The core of the idea of Borderlands was simple enough to do, without much experience, within a five- to six-week period, but getting a product together - and I don't really think of it as a product these days, but to get it into the App Store, you have to harden it a bit and get all the extra bits like a tutorial and settings page, and learn how to make a table view, and do all this extra stuff around the edges of the central piece -that stuff took a really long time to get to in a way that felt good for people using the app.

I mentioned earlier that the first version was a little bit of a train wreck, which is very true…when I finished that thing up, I was working on it towards the end of grad school, so I was finishing my master's degree. I had a summer where I was searching for a job and was unemployed. We were living in California and rents were going up like crazy, and it's like, “we gotta move out of here.” My wife’s [employer] downsized, so we had a month where it was like, “okay, we really gotta find a place to go.” And so I was trying to wrap this thing up, working during the day at home and then searching for jobs, and I got it submitted to the App Store before I started my job in Portland. It was still a prototype, basically, when that one came out. I mean, you had to load sounds from a playlist named Borderlands. You had to put a playlist from iTunes to the device, and this was my workaround for getting stuff in there because I didn't know how to deal with the file system on iOS properly. So I was like, “all right, people are fine putting playlists on things. They're not going to have a problem with that.” And sure enough, that was not something people were super into. You couldn't save it, you couldn’t save presets. It was really designed, at that point, to be like a sound generating toy for the studio. That's how I thought of it at that moment in time, was like, “it's just a sound design tool. You make some stuff, you’re going to take it off the device, and that's it.”

And then, AudioBus came out like a month later, and I was like, “Oh gosh, I don't know. I don't have the time. I just started a new job. How am I going to do this? My inbox is getting hit with tons [of requests].” The number of requests for AudioBus support [was crazy]. And at the time, Borderlands couldn't do it, performance-wise. It was just too much lift for it. At that point in time, I think the Audiobus developers, had a rule that was like, “we won't announce your app if it can't run reliably at this buffer size.” Well, Borderlands was just miserably failing at that. So I took a long time to get that in there. And fortunately, by 2015, three years later, when that version came out, it was able to do it on the iPads of that generation.

I had this pivotal moment in 2013: I got invited to do this gig at Sónar, which is where I met Marcos [Alonso] for the first time. They had found out about the app through this art competition I had submitted the app to, and I got this email like May 20th, “Hey, Chris, what's the live performance like?” And I was like, “I guess I must've mentioned something about a live performance…I do perform live with the app, but not very well or not for long periods.” And they were like, “can you do a 40 minute live performance with the app, just using the app? We want to have it be part of the Sónar+D technology showcase.” Being just out of school and everything, I was like, “yeah, sure. I'll do it. I've never had an opportunity like this. I've never been to Europe before.” I had three weeks to get the app to a place where it could perform live in front of people halfway across the world, and also figure out how to go to Europe for the first time and get all those logistics sorted out.

And so, that forced me to think about the app as a live performance tool and something that needed to be hardened enough to work on stage. In the process, that was where I made the initial implementation of the “scenes” functionality. I had the idea, “all right, if I can save presets, then I can have two iPads, go back and forth between them like turntables, and perform with sets of sounds.” I spent so much time developing it that I was making the music on the plane on the way there and in the hotel room to do this thing…I think I sent you a recording of [the performance], but it says “part three” because the first two sections are total crap.

Andrew: For people listening to this, yeah, I have a recording of that Sonar 2013 set that Chris did, so I'll share that on the page. I think it's like a really interesting piece of history for Borderlands.

Chris: Yeah, it was this totally terrifying and exciting experience. And coming out of that, I was like, “all right, this needs to work live. And it can be an instrument for the studio, but it has to be both.” My focus, after having to make music with it and do a live performance, really turned towards like, “how can I make it easier to improvise with this?” Expand the scene saving functionality, get it easier to import sounds, the automation - the motion automation for all the parameters and clouds…that was something that kind of started on a whim, and then became the core feature of that next version.

I'd really been inspired by this app from Scott Snibbe called “Motion Phone” back in the day. You could animate and automate shapes on screen and they would replay your gestures, and I thought, “you know, I'd love to have something like that in Borderlands.” So that was an idea that was there early on, but took a few years to make it into the app.

And then, I feel like every iteration of this app…I release a version and I'm like, “all right, I've released the version. Now I can start making small, incremental updates, and people will be happy because it'll keep going.” And some big, sweeping life change happens at that exact moment, or three months after the app comes out. So after that version, we got pregnant with our second kid, and then we decided to move cross country.

Andrew: No big deal.

Chris: Yeah…so I started working remotely. We lived in Pittsburgh for 10 months during that time, and it was just not the right time to [be there]…it was winter time, we had a kid, I didn't know anybody because I was working from home, and so we ended up moving again to Virginia to be closer to family. And then it took a year to get back to developing and I got the version in 2020 out, and then the pandemic hit.

So that leads us to where we are right now. I guess I've been, since the pandemic hit and that version came out, just been iterating a lot on stuff, but with family life and work and everything, it's just really a challenge to get meaningful progress in the way I used to. There's still stuff that from those early days that is on my list and showing up, and going to be in the next version.

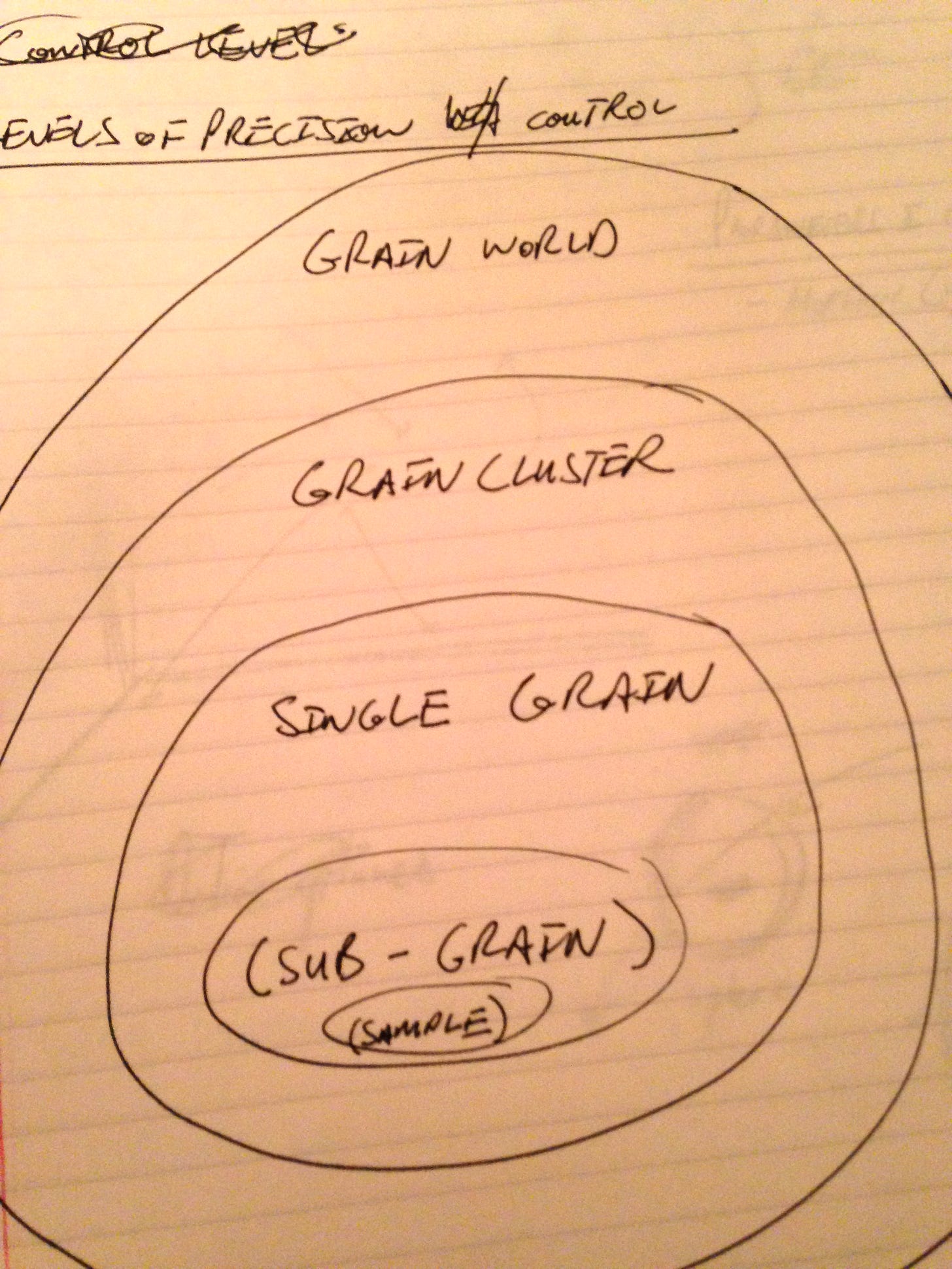

I think I sent a sketch of an image of from the original idea for the app, where it has “grain world” and then it's concentric circles…it's like “Grain World,” or Borderlands, then “Grain Clouds,” “Grain Voice” - which is just one of the grains - and then it says “Sub Grain.” When I found that the other day, I was like, “Oh my gosh, I had forgotten that I had written that down.”

But that's one of the big pieces that I'm focusing on in this new version, is this idea of “what happens when you divide a grain into smaller pieces?” Technically, it's just more grains. But this idea of sub grains, or amplitude modulating an individual grain voice within the app and playing around with the frequency of that modulation, or what happens on every cycle of the modulation [such as] potentially changing pitch every time we hit the end of the cycle, is leading to these really insane sonic results. Now, instead of having all the grain shapes as buttons on the top, I've moved them into a slider and you can change the shape of the primary grain. You can also change the shape of the sub grain and the frequency of the sub grain underneath the main sub grain, and then shift the phase of them and change how the pitch cycles. And so, I'm just super excited about all that stuff.

But because it's leading to this explosion of parameters around that, I'm currently working on taking the parameter sets and making kind of a simpler [view]. Hopefully a simple pagination of them so you have those radial parameters coming out from the main cloud instead of all the extra buttons, because a lot of that stuff is moving into sliders now that you can automate. There'll be just text, is what I'm thinking, but it'll just be like “main page, grain shape, filters,” etc…and then you'll just toggle between them pretty easily.

But, again, I’m back to fighting my old decisions that were made, and trying to even just figure out what I was doing at that point in time. It's taking so long.

Andrew: Yeah. Well, I've seen you share clips and snippets here and there on Instagram with stuff that you're working on. All of that sounds incredible. I also saw that you posted a little teaser clip of Borderlands running on an iPhone, which to me is amazing. Like, “head exploding” emoji happening right now, because I make so much of my music on my morning commute on the train. That's why I love mobile music making so much, and iPad and iPhone and tools like Borderlands, to me, are really essential ways of working…and yeah, using it on a phone would be just next-level exciting.

All that stuff is so cool, to see what's coming up down the road. Looking forward to all of that.

Chris: I'm excited to get it on the phone, as well. It's one of those things where - it's worked on the phone for a long time. I have an old iPhone 5 or SE, I think is what it was at the time. I remember just on a whim one day being like, “all right, it's going to look terrible, but I'll try compiling it on the phone.” And it worked. It was actually working better than on my iPad, it was just impossible to touch anything because it was so small.

[But] that’s the plan. I am pretty committed. I'd say 99 - I'm not gonna say 100 percent, because who knows what can happen - but 99 percent sure that's going to be the big piece of this next update, is making sure that it's on the iPhone and universal. I want it to be iPhone, Mac, or iPad. There's an option where you can run the iPad app on Mac as well, and I've been doing a lot of testing with that, actually. So some of the Instagram videos lately have had my mouse in them, and that's because it's actually way easier to not have to pull out the iPad every time I want to test out feature stuff. I've run it that way, but I'd love to make that available for people because, especially with doing things with open sound control, if you're working with Max on your computer and using that to control Borderlands, if it's a local connection, the transmission is - there's no latency, so it ends up being…you can do some crazy stuff. I had Max manually triggering grains, and the grains reporting back that they'd been triggered, which was then triggering parameter changes in Max, which were then feeding back into other parameters in Borderlands.

Getting it on the iPhone and getting it opened up a bit where other things can talk to it - I feel like [that’s] really the future of the app, where it can move beyond just being this fixed thing and can actually expand outside the bounds of the iPad. Getting pan and zoom capability so that I can scale it down so things aren't too big on the iPhone, as well, is an important piece of that, but yeah.

Andrew: So cool. Yeah, I'm so excited for that. Kind of a full circle moment too, enabling a desktop version of it - I guess that would bring it back to its roots, in a way.

Chris: It would be. Yeah. It's true. Amazingly, the original desktop version will still compile and run on my M1 Mac, which is just crazy that's possible. I think it just shows how little was actually in that. It has very few dependencies, so it can still run. It's a weird little beast.

Life outside Borderlands

Andrew: That's awesome. Well, just zooming out from the app a little bit, I'd love to focus on you as a person and human being, and not just the bits and bytes of code that you're writing.

I was poking around on your personal website, and it describes your work as “building interactive experiences for cultural institutions.” I'd love to hear you talk, if you're okay with talking about your day job - what is the work that you're doing with that? I mean, I saw a whole litany of cool projects on your portfolio, but if there's any that stand out to you, I'd love to hear about that.

Chris: Yeah, absolutely. Happy to talk about it. So, a lot of the projects on my portfolio are from my job. I mentioned earlier, we lived in Portland for a period of time, and then moved to Pittsburgh, and then to Richmond. Those projects were for a company called Second Story, which was a small design studio based in Portland. That was my job straight out of grad school. I went there as an interactive developer, so kind of doing - openFrameworks is a kind of creative coding framework, wrapped around C++, that you can use to do more interactive art projects. And so I worked as a software programmer for them for a few years. Well, no, not just a few - 10 years. Feels like a few, I don't know why.

Once you have kids, it's, “10 years, what? Crazy. That was only two years ago, right?” And the pandemic too…

Andrew: Yeah, I know…it’s a whole big time warp. It’s nuts.

Chris: I don't understand this whole aging thing.

But yeah, that job was really focused on building interactive experiences for museum exhibits, so I was doing multi-touch interactives, things with LED lights, connects, and other sorts of things.

Around 2020, it was a very unfortunate timing of events. Pandemic started. Second Story had been acquired years back by a much larger company. Actually, two weeks after I started, I found out that they were part of this huge company, which was exciting and weird to find out. Not exciting - that’s [sarcasm]. It was a scary moment. “This company I'm joining is not what I thought I was going to do.” Anyway, over time, they eventually dissolved and the parent company dispersed everyone right at the start of the pandemic, which was not the best timing. I worked for a company called Razorfish, which was also owned by the parent company for a few years. And then just this past year, I left that job and I'm now working at a company called Art Processors, which is kind of back in the same domain as Second Story, working for primarily cultural institutions doing exhibit design and creative technology. So we're trying to find ways to tell stories for our clients, and create really impactful, immersive visitor experiences.

The thing I love about doing this type of work is it's [similar to] building a musical instrument or an app. it's really focused on making things that are meaningful, and either educate people, or excite people, or inspire them or bring a smile to their face. That's what I love about doing this kind of work, is that you get to work with so many different types of technologies, but it's not just the technology. It's about creating something beautiful, or telling a story, or guiding someone to look up and experience a space totally differently.

I love my job. It's really awesome. And I feel like it's just a really good complement to my personal interests in music, sound stuff, and working on Borderlands.

Andrew: I was gonna say, I mean, it seems like a very logical parallel to the work that you're doing on Borderlands.

I always love hearing especially from musicians and creative people what they're up to outside of music, and what informs the work that they do on their musical pursuits. It's good context to have, I think, in understanding where you're coming from and what you're doing on a day-to-day basis, and what you bring home with you when you then sit down to work at the app.

Chris: I reply to people frequently on Instagram posts about the app, “sorry, it's coming eventually. I've got a day job and I've got kids.” In the early days, a lot of people thought it was a company making this thing. And then eventually, people realized it was just an individual working in their spare time. But I always feel like I have to apologize for that, but it's…man, it's interesting, but it's also great because it does inform the app, and they both sort of inspire each other in a way. A lot of time at work, I'm doing more project management and things that don't necessarily involve being directly in the tools and making stuff. And so, you know, to have Borderlands to work on in my spare time gives me that outlet, and then I go back to work with ideas when it does become time to do something with sound or maybe spatial audio. Some of my experience from making things in the app, or the ideas that I'm generating there, can sometimes inform those creative processes conversations.

Andrew: Yeah, absolutely.

Chris: This industry is a pretty small set of people, and there's a number of folks from my prior company who are working at Art Processors now. And the amazing thing about it is, everyone is there with a secondary passion outside of work, too. They come from an art background, or they come from film, or sound design or whatever, and it's a really interdisciplinary crew of people. So I get to work with designers and writers and filmmakers and make really cool, beautiful stuff, which is often very hard to get across the finish line. Building museum exhibits is a long and arduous process.

Andrew: Yeah, it’s probably a long runway to reach completion on those projects.

Chris: Yeah. Yeah. There's always different challenges, but you know, the end result is always something rewarding, which is the best part of it.

Andrew: Yeah, that's cool. My day job is probably as far away from creative music making as you can get, but people ask me all the time, “would you want to do music full time at some point?” I'm not sure I would, because I kind of value having that other part of my life that I can not be absorbed in my own head all the time, and I have something else to focus my energy towards.

I like hearing from people about what they're up to, outside of music beause I think that's pretty informative.

Chris: So, what's your day job?

Andrew: I work in logistics and supply chain, specifically in risk management for that. So, finding ways to prevent disruption of the supply of goods and services. I work for Comcast here in Philadelphia. It's a very tactical, very “project management” and “process” kind of focus, and that's definitely the way my brain works. I'm always thinking of steps in a process, or ways to improve methods of doing things, which is why I think I like doing this Substack page that I'm doing: I break down the workflows that I use, and explain what's happening step by step.

[It’s] just that process-oriented brain of mine. It comes out one way or another, whether it's my job or my music. It's just the way it works.

Chris: Yeah. So that's so great. Yeah, having something that counterbalances your creative practice is so helpful because I find that the times when I have unlimited time to work on Borderlands, or my own music, those are the times I get paralyzed and I can't make any forward momentum. If I had to do that all the time…I mean, as much as I would love to be able to just wrap up Borderlands, get everything in there and do it in a month - take a month off and just push through - I think your creativity benefits from a forced kind of pacing, you know, where it can breathe. I think if I had 20 days in a row to work on Borderlands, I would just find myself constantly redesigning things. But if I have a break and can let things breathe, you know, some of those ideas that should be on the cutting room floor do go on the cutting room floor. Or they go in the notebook and get saved for much later.

Andrew: Yeah. And we were talking before we hit record on the interview here about how we had just put kids to bed before jumping on the call to have this discussion.

My day, pre-kids - and you're a dad, so you know how it goes, obviously - but in my pre-kids life [I had] so much time available to work. I made a lot of stuff; I made so much music, I was constantly churning out ideas and stuff like that. But at the same time, I'm kind of glad that I don't have that much time now. I think it has absolutely focused my brain on what it is I'm trying to do: “What do I need to get done? What do I want to get done?” Rather than just kind of sitting in an endless loop of ideas and paths to go down. I'm definitely a more focused creative person now, with more limited time and constraints on what I'm able to do. I think it's been very helpful for me.

Maybe you relate, maybe this is the same for you.

Chris: Yeah, it's…I don't know, you were describing having endless time to just think through ideas and it sounded really good. [laughs]

Andrew: [laughs] As a chronic over thinker, that's not good for me.

Chris: Yeah, I do the same. I know, it goes from ideas into anxiety pretty quickly.

It's been interesting. I mean, we have four kids - and we're done at four - but my wife grew up in a big family, and so we wound up going that route and it's awesome. I mean, they're all amazing, but it takes so much time and so much energy. And now that they're older, the hard part is the big kids stay up a little later at night. It used to be that we reliably would have, “okay, it’s 7:30, we can get them to bed. Then I’ve got three hours.” Or, in the early days I used to stay up much later, and not feel totally wrecked the next day. I could get a good chunk of work done, but now it's, “Oh, maybe I start at nine, and I can work for an hour before I'm falling asleep at my desk.”

But yeah, you have to get more organized. And I found, at least for our family, just planning ahead, like “these are the days I'm going to work on it, and these are the ones that I'm going to take for just being away from it.” Back when we just had one kid, I would work weeknights on Borderlands, and we'd take weekends just for family time and I wouldn't do any Borderlands stuff. And that was great, beause I was able to really get a lot done that way. And now it's like, “all right, maybe we just fit it in around things.” But it's still kind of that general mold. We'll work, just having some structure.

Andrew: Yeah, [with] my process-oriented brain, again, I’ve got to pick out days that I do stuff. I like having a little bit of order and consistency to keep me focused. Otherwise, I just get into a doom loop of endless thinking and dreaming and never actually get anything done.

Chris: Yeah, I'm a procrastinator/avoider…if I have too much time, the thing I want to do, I will just not do, and that's a challenge.

Or, you know, if it's something that I know is going to take four hours to do, to figure this out, and I'm just not going to have the time, I'll just avoid it and then get to it when I have a full day.

It's not [always] possible to end up getting that hour in here or there, but it's always changing.

Andrew: Well, speaking of “getting an hour in,” an hour here has flown by remarkably quick. If you're up for it, I'm going to ask one more question.

Next for Borderlands

I'd love to hear about what's next. What's next for Borderlands? What's next, in terms of timeline? What can we, the eager public, expect to see out of you in the foreseeable future here?

Chris: Yeah. Well, timeline wise, I've been kind of notorious for making optimistic assessments and then failing to meet those…

I feel like between version two and version three, or whenever it was - the version numbers were all messed up - I would be like, “I'm going to do my best to get it out in the next six months,” and then it wouldn't happen. So I'm always reluctant to make statements about when I'm going to get it out, but I'm trying. I would love to get something out there within the next year, but I have a feeling it could be very late in the next year based on how I'm averaging like an hour a week right now. I'm working on it less, but the things I am working on, I'm super excited about the direction it's going. This stuff I was talking about with the sub grains earlier - I feel like that has opened up a door. I mean, interaction wise, nothing is really changing all that much, but there is a lot more territory to be explored sonically, which is really fun.

I think I'm always thinking about ways to enable more control, and also complexity, so another thing I've been thinking about, which I haven't started on and may or may not make it into this next iteration, is the idea of “cloud formations.” So, grouping clouds, maybe grouping them so that they can both be controlled simultaneously, or one can influence the other, sort of like global controls for manipulating parameters across the entire app. One sticking point for me for a long time has been not being able to easily double or halve a parameter. I need to find a way to do that that makes sense, that makes it quick and easy. Things like that, little details like that…but then also pan and zoom functionality so you can move further out and make a bigger canvas, or even just to enable it on the iPhone, to scale things to a comfortable level. It's really important.

But as far as big features go, it's really thinking about [how to] get it on the iPhone, get the new fun features that I think of. I like working on things that enable exciting new sounds. That’s a big one. And then, I'd love to have some form of the open sound control stuff in there, too, for people, but that may wait. I wanna get to a point where I can actually have some example devices to map to release as well, to control the app. But yeah, the priorities are wrapping up the parameters and the iPhone version.

AUv3 and beyond

And then, yeah, I know AUV3 is a big one that people were…

Andrew: Yeah, I can't imagine your inbox. It's gotta drive you nuts.

Chris: It’s not too bad now. I think I've said “no” enough times…I'm not sure. I know Marcos talked about this on his podcast with you, too, or his interview with you. It’s one of those things where it's such a big effort to implement it. I don't even really quite understand everything that I would need to do yet. There's not a lot of great documentation out there on how to integrate it into an already functioning, full screen OpenGL-based app. There’s some example projects people have, but the process is a little intimidating and it's something that I've been a little reluctant to do just because it involves tearing apart so much. Because of that, I tend to want to be like, “all right, I've got to finish things, get it stable, get a small testing group going, and then I'll look into that when it's at a place where I know I've got most of the features in there, and I can really focus on just doing that thing - doing the AUv3.” It’s something I would love to do still.

I do have a little bit of - there's a philosophical discussion to be had about full screen apps versus windowed apps on the iPad, which we should chat about some more. Practically, the issue of needing to implement resizing for the app…I don't think it's a huge deal because it's working on something iPhone Mini-sized at this point, so I have to just figure out what to do with table views, and the scene browser, and those sorts of things. But I know the audio engine, for example, needs to be refactored a bit to make it work in that context, and to support multiple instances of AUv3 plugins. There’s a lot of different challenges that I feel like, with any new feature, when you start going down the path of implementing it, all of these special cases and unusual things unfold in front of you as you're going down the journey, or climbing the mountain or whatever…there's all of these unexpected challenges, and this is one where it feels like I'm going to start on this and it's going to turn into three years of work. So for that reason, I've sort of held it out there.

Andrew: Yeah. It brings to mind Chris Randall from Audio Damage. I see him posting on social media occasionally, and he has a very caustic sense of humor about all of it, but he talks about how a lot of the development process does seem to be a little murky. Especially with Apple and their very unique ways of doing things. It seems like there are a lot more hurdles to some things that may seem simple on the surface, like yeah, “why can't you just make it an AUV3? What’s the big deal?” But there's actually a lot behind that that is difficult.

Chris: Very difficult, yeah. There are audio engine changes that need to happen, and then the UI challenges, actual project infrastructure, setting up the project to support an extension in addition to the main bundle of the app, main target of the app…yeah, it's just a lot of different pieces, but the other piece is that Borderlands has benefited from using very few iOS-specific things beyond what's necessary. It's using UI buttons and table views, and that's almost it. Because of that, it's held up against the update cycle that Apple has and it hasn't had too many issues where it's suddenly not working for people four years later. It's been able to stay in the store for a long time without problems, so I have the sense that implementing AUv3 - because it's also a changing technology - will introduce all sorts of problems that will require regular maintenance and updates. That's a lot harder for me to do, just because I'm a one man show, working with the job and kids and all that…but, it’s worth it if I can get everything in there and get it working.

I do love the idea of people being able to use it in more contexts, and I think there's probably opportunities with AUv3 that I'm not even aware of yet that would unlock some really cool potential in the app as well. I’m not just full out dismissing it, but there is something in me, though, that also just really likes that the app has the full real estate of the screen - and that's how it was designed. But I also think it's valid to have it in all contexts, if possible, so I would love to get it there eventually. But it probably won't be in this next iteration. That would put the release date out like another two years or something.

Andrew: Yeah. I mean, to me, [AUv3] is not a huge deal. I see other people clamoring for AUV3 on this and Samplr, and it's just like, “all right, guys.” It's not a big deal to me. I kind of like having it as a purpose-built app: I open Borderlands, it does Borderlands, and it stays in its lane. Otherwise, I think you're just opening up too many options, potentially, but yeah, like you said, maybe we get there someday. But to me it’s not a huge thing.

Sorry to anyone listening who I'm disappointing.

Chris: If I were a better businessman, I would probably already be on top of it, but I've always focused on the app as a way to express the things I'm interested in and care about, and to explore my own ideas of how I could make music. It's been an amazing joy that so many people have also connected with it, and that it's gone out to so many different places, but it's not something that I'm able to rely on for my [income]. It has to conform to the time and space I can give to it. I hope that I can keep it going for a really long time, because there's so much I want to do. I just don't have the time.

Andrew: Well, whatever comes with it, I think I speak for a lot of people in saying that we're looking forward to it.

This was great, Chris. Thanks so much for spending this time and giving us a little peek behind the curtain, not only into the app, but also into you as a person. This was a lot of fun to have the conversation and I appreciate you taking the time.

Chris: Absolutely. My pleasure. Thanks so much for having me. It's a treat to be able to talk about the whole story. I hope I didn't ramble on too much.

Andrew: I love it. The more detail and more context, the better. So it's appreciated.