I have to say, I’m really excited about this episode with

and Joe Branciforte. We recently spent over an hour together, jumping all over the map chronologically (from the late 90s to the present) and philosophically (from electronic microsound glitches to extended woodwind techniques) while discussing an incredible project they’ve completed: a reimagined, reinterpreted, and re-recorded version of Taylor’s seminal 2002 album, Stil.The minor typographic change in title (note that this new album is called Sti.ll) belies the depth of transformation under its surface. Recorded entirely with acoustic instrumentation performed by humans, rather than lines of code on Powerbook G4s, this new edition is a complete and total reinvention of the original. As I discussed with Taylor and Joe, it feels to me like a new and separate album altogether, with its own story to tell.

I’m a huge fan of Taylor’s music, and essentially everything else he curates and releases through his label, 12k. It’s a massive catalog of work to dig in to, but if I was forced to choose only a handful of albums to introduce a new listener to this “Deupree/12k” sound world, Stil. would undoubtedly be included in the mix. It’s a master class in minimalism and repetition, but also a perfect introduction to Taylor’s unique voice. It’s a hypnotic collection of melodic granular loops, placed and arranged in such a way that subtle rhythms and pulses seem to unfold and branch off into new territory as time goes on and the layers converge, merge, and expand. The longer you listen, the more engrossing it becomes, and the more details you pick up on…it’s a classic of the genre, in my opinion.

The original album is a distinctly digital and austere creation, a true product of the early 2000s microsound era when boundaries were being pushed in new directions with “laptop music” and digital processing that pushed the machines to breaking points. Understanding this context and the tonality of the original is, in my opinion, essential to understanding this new edition. If you know what Stil. is about, even vaguely, then it makes it all the more remarkable when you hear what Taylor and Joe have made with its successor Sti.ll.

Everything on Sti.ll was performed and recorded by humans and captured through a microphone. No, that’s not a typo. Loops, fade-outs, hiss, digital glitches and faults in the original - all of these things were recreated with human hands. No loopers, synthesizers, or digital instruments. When I heard it for the first time, I was awestruck. “How does this happen?” was about the only thing that entered my brain during the first 2 or 3 times I listened. I almost forgot to absorb the music at all, as I sat transfixed by the techniques I was hearing.

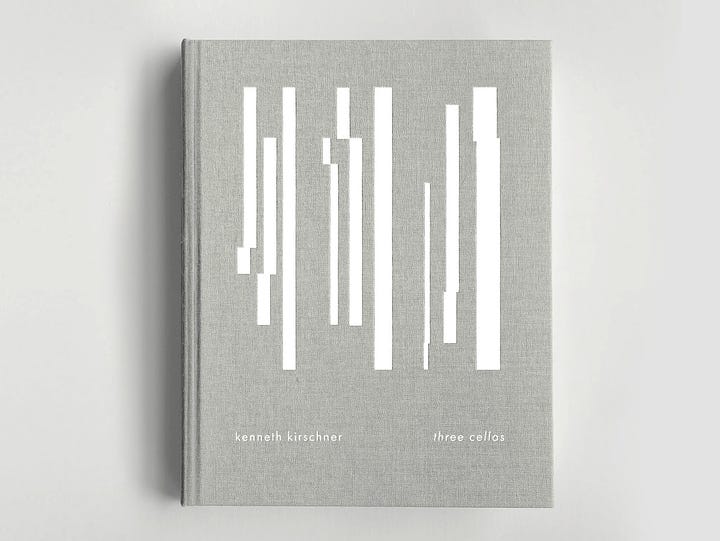

If there was anyone who’d be up for taking on this kind of task, it’s Joe Branciforte. A multi-instrumentalist, composer, and Grammy award-winning recording engineer & producer based out of New York, he is the founder of the record label greyfade, which primarily presents work from artists exploring process-based composition, electronic & acoustic minimalism, and alternative tuning systems. Joe’s experience with acoustic, electronic, and algorithmic composition, performance and improvisation makes a near perfect match for this kind of project. His work with Kenneth Kirschner and Theo Bleckmann, in particular, are prime examples of his unique abilities in composition and live electronic processing of acoustic instrumentation.

Hearing Joe and Taylor discuss the albums - both the original and the remake - was an awesome experience. You can tell that this experience left a mark on both of them, and I’m glad to have had the opportunity to hear about it in this interview. They bring a whole new degree of understanding to what was, truly, an extraordinary undertaking.

Here’s the full transcript of my interview with Taylor Deupree and Joe Branciforte. I spoke with them over videoconference from Taylor’s studio in New York on the night of March 21, 2024.

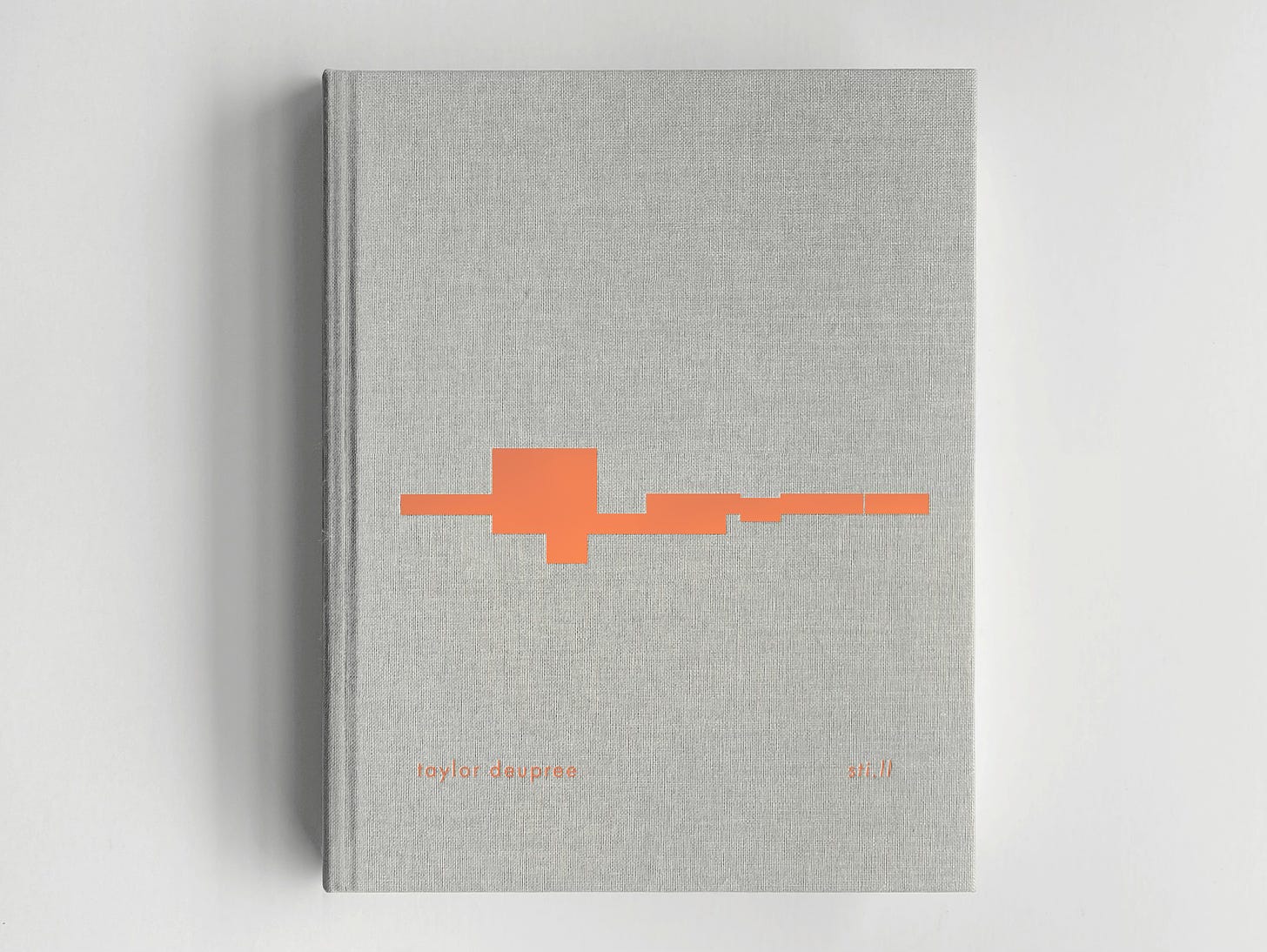

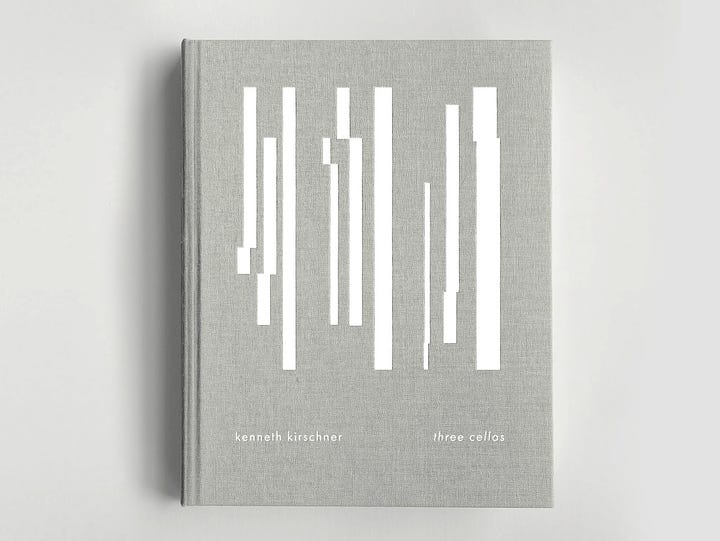

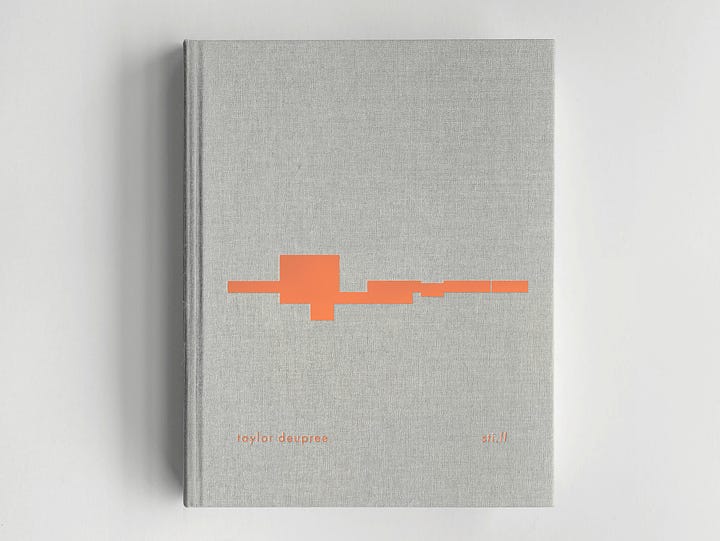

Sti.ll is a collaborative release between labels Nettwerk, Greyfade, and Deupree’s own 12k, due out on May 17th. Along with a vinyl release, Greyfade has announced a special edition hardcover book as the second installment in their FOLIO series. Support the artists by preordering the album on the label page as well as Bandcamp.

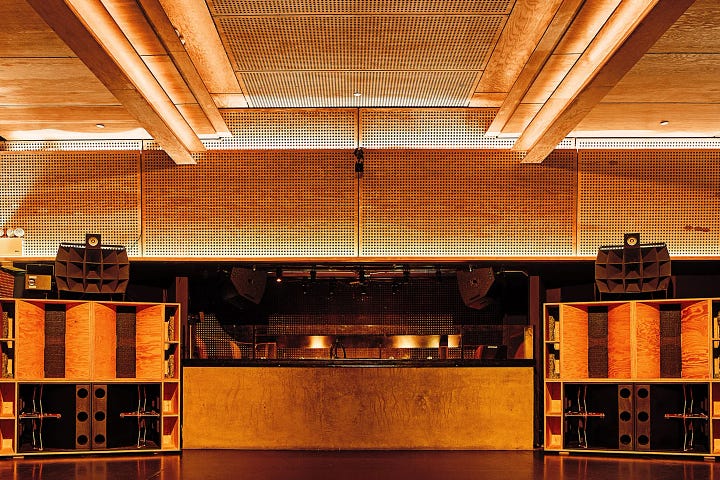

Note for those in the US: there will be an album release show at Public Records in New York City on May 22, 2024, featuring Taylor & Joe alongside some of the album’s personnel. Opening sets will be provided by Jack Quartet and Joe Branciforte & Theo Bleckmann. For tickets, visit the information page here.

Transcript

Sound Methods 007: Taylor Deupree and Joe Branciforte

Andrew: Taylor Deupree and Joe Branciforte, thanks so much for being here on Sound Methods. I appreciate you taking the time.

Taylor: Thank you for having us.

Joe: Yeah, thanks for having us.

Andrew: Yeah, of course. And like we were talking about off camera, I have a really long list of questions about this album that we're talking about here today, and that is a reimagined version of Taylor's Stil. album, originally released 22 years ago now…I think it's 22 years? Correct me if I'm wrong, but I believe that was 2002, when the original came out. Congratulations, first, on completing this mammoth project. It's a re-imagined and re-interpreted version of that, using acoustic instrumentation, which Joe was instrumental in helping develop. So congrats to both of you on wrapping that up.

And so, my first question here is for you, Taylor - I'll get to you in a minute, Joe - but there's a relationship here between Stil., the original, and then the album that preceded it, which is Occur. And I forgot about this, actually, until like a week or so ago when I was listening back to the original Stil. and reading through the liner notes and all that, and you made reference to that fact. Hearing those two albums next to each other is a really awesome contrast, I think…right after listening to Stil., I flipped on Occur, so I probably went in the reverse order. But, Occur is full of all these random and almost incidental sounding digital artifacts and whatnot.

It's such an interesting contrast to the steady and repeating tones that are in Stil. I think people should listen to both of those albums together, for sure, but I'd love to hear you offer some commentary and take us back to that point in time, and explain what your headspace was like after finishing Occur back then and then beginning Stil. What prompted you to pursue that kind of juxtaposition of the two at that point in time? I'd be super interested to hear your perspective on those two albums and how they came to be, that close together.

Taylor: I'll start by saying when I'm done with Joe, and no longer want to be friends with him, I'm going to ask him to reimagine Occur…because if you thought Stil. was hard…

[laughs]

Occur is next.

Andrew: I wasn't going to bring that up, but I'm glad that you did. [laughs]

Taylor: I don't exactly remember what my headspace was, even if I had intended to do [it that way]. Occur came first - it must have been ‘99 or 2001, or something like that. I don't think I intended to do both of them when I had done Occur. I may be wrong, or remembering it wrong, but I don't think I imagined them as, at the onset, as a duo or a diptych of some sort. Stil. was more of a response to Occur - and I'll get into it in a second, but when my headspace sort of changed I saw the two as, like you said, as being real opposites. And because they were so different from each other, they worked together, in my mind.

Occur was really a product of the time. I think it was the height of what they called the “microsound” movement, and the beginning of really being able to use laptops - or, I shouldn't say laptops, just computers in general. I don't think I was using a laptop to make it. [Artists were] using computers to really Zoom in on sounds and be able to edit at this microscopic level. At the time there was so much…it was this glitch, sort of microsound and glitch era of music, where there wasn't as much music as there was noises, and little glitchy errors and stuff like that, sort of abusing the edges of the computer processing. I probably talk about it in the press release for Occur, and I don't remember what exactly that says, but thinking back to it, it's almost like Occur was…I mean, I know it was an album about sounds around you that happened briefly and then disappear, things that only happen once and then they're gone. It was very much about ephemerality and a sound - a car that passes you by and you hear it for a second and you'll never hear it again, and every car that passes you by is different, it's never the same - so Occur was, like you said, was very random and a lot of non-musical noises and things.

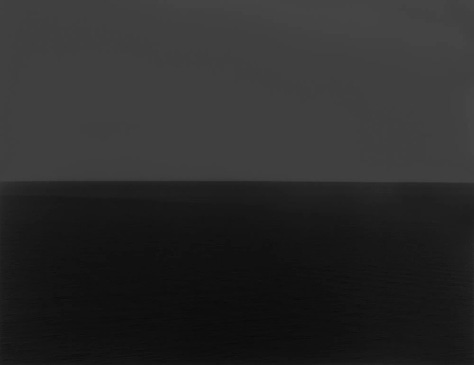

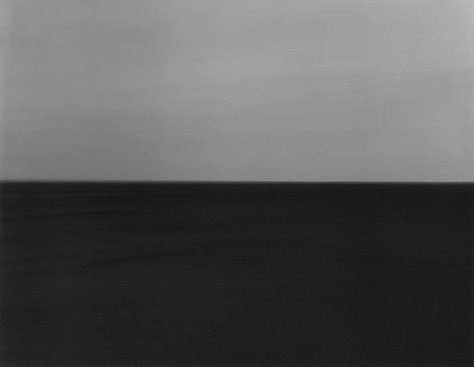

And then sometime around the year 2000, I was introduced to a book called Seascapes from the photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto, and that book changed my music forever, and still affects my music today. And this is a book, for those who don't know, of pictures of oceans and seas taken around the world - black and white photos - where the horizon line between the sky and the ocean is dead center in the picture, and the pictures are equal part sky and water. When you flip through the book, a quick look, you'll say “every picture is the same. They're all the same. It's water and sky.”

And that's what struck me so much is that, well, all the pictures were “the same” but they were all vastly different, and that had such an effect on my music, or just my creative head. I wanted to make music that appeared to always be the same, but was always changing: this idea of using looped passages that were always subtly different, and that's what Stil. was. So, where Occur was all random sounds happening once and disappearing, Stil. was the stillness of repetition, but with constant, minute changes.

So, maybe a lengthy answer, but maybe that gets to it a bit.

Andrew: That's exactly what I was hoping to get at. And, while you were talking, I was pulling up Hiroshi’s Seascapes images. Definitely something I'm going to explore more in depth after we wrap up our conversation here. But that's super interesting insight. I appreciate that.

And yeah, going back to the Occur liner notes, I love the evocative mentions that you make of quiet urban sounds all around us that come and go, and then are gone, and [Occur] definitely comes across that way. It just…I don't know, it gave me a very interesting experience after hearing Stil. and going in the reverse order chronologically; I guess it was fascinating to make that comparison between the two.

And with that, that leads me into the next question that I wanted to ask you. In thinking about your music over the years, this is just me interpreting it, but going from that era of your music making and then listening to what you're doing now…if I had to explain to someone how I'm interpreting it, it's almost like a seesaw, where you're balancing one side of very analog, imperfect characteristics, and then on the other side is this digital processing that occurs. I think throughout your career so far, there's always been a balance of those two things, and it's just a matter of how much you're choosing to reveal at any given point in time.

So this project in particular - the reinterpreted version of Stil. that you and Joe have made - I think it's almost like a perfect representation of that, where you've got the original, which is very digital and very repetitive in nature and computer dominant, and then coming to this version…it's amazing, making the comparison between the two, because they are similar, but they are so different. I'm wondering if you think about that duality at all, between the digital and the analog, and the way that you make music. Is that the way that you're thinking about things, or does that resonate with you at all? I would just like to hear your perspective on that, or reflections on that process that you have developed over the years.

Taylor: Yeah, completely. I think about it every day. Fortunately or unfortunately, I need technology to make art. I consider myself an artist - it's what I've done most of my life - but I've always needed technology to do it, whether it's a camera or synthesizer or something. I'm not a very good illustrator, or painter, or guitar player, so I've always needed this sort of crutch of technology to realize my art. Lately, in the last 10 or 15 years, I'm less interested in the sound of technology and more interested in the sound of nature and acoustic instruments, but I still need that technology to do what I do. In the studio, I'll use guitars and I'll use acoustic instruments, but they'll be handled or processed with technological means, and I'm very much interested in the balance. My music is generally all about fine line balances.

Back in the day, the original Stil. was all digital, one hundred percent. This new version is, like you said, the complete opposite realization, where the one rule that Joe and I had for ourselves was “everything has to be recorded with a microphone.” Even the microphone is electronic, or electrical anyway, so we had to compromise there, but nothing is plugged in directly. Everything resonates through the air, between the instrument and the microphone. Nothing is ever directly connected via a patch cable. It's as acoustic as you can get on a modern recording; the only more acoustic version would be a live version. That was really the one rule that we had, that everything is recorded with a microphone.

Andrew: I love that. That's a really interesting rule for an electronic musician to follow.

Joe, I was reading through the greyfade press release for the album, and I think you made mention in there about almost being…I don't know if you use the word “afraid,” but you had some caution when approaching the project because of the respect that you have for the original recording, and you were wondering if it was a good idea or not. I found that very relatable, because I put myself in your shoes, approaching an album that I love and thinking of a way to take it to a new place. I'm sure that felt like a very daunting task.

I'd love to hear your perspective now, after a multi-year process of working with this material, and treating it and shaping it into something brand new. Maybe this is kind of a loaded question, but do you think that that fear was justified at that point in time? What were you most afraid of going wrong, and how did your thinking evolve over time as you worked on the project with Taylor? Was your stress going up or down as the process unfolded?

Joe: Up, and then it went up until it went down. [laughs]

But I think it's an experience that I've had at several points in my time working. I'm a recording engineer - I guess that's my day job - and producer, so I've had the experience a number of times of stepping into the studio with someone whose music I've listened to since I was a teenager, and there's a certain uncanny feeling where you're really used to relating to that person, or that canon of music really, as a, a listener, as a fan, and now you're being asked to take a more active role and to kind of…part of the fear for me almost like, I have such a nostalgia over certain works and certain pieces of music that it’s almost painful to try to reimagine it.

In this instance with Stil., I was like, “well, what could I add to that that would make that better? I love the album, so I don't know if I want to change it.” But on the other hand, having an invitation to work on something like this, it was exciting in a certain sense because it was a challenge. The challenge of it took over and overshadowed any reservations that I had about it, eventually.

The beginnings of the project were pretty casual and I don't think either of us really knew what we were embarking on, necessarily. It was sort of an idea that Taylor mentioned over email, and when I got the email, I was kind of like, “well, this seems like it would be hard and take a while.” So I had to really think on it, but I think when I started to become really personally excited about it was when we started working on the first piece.

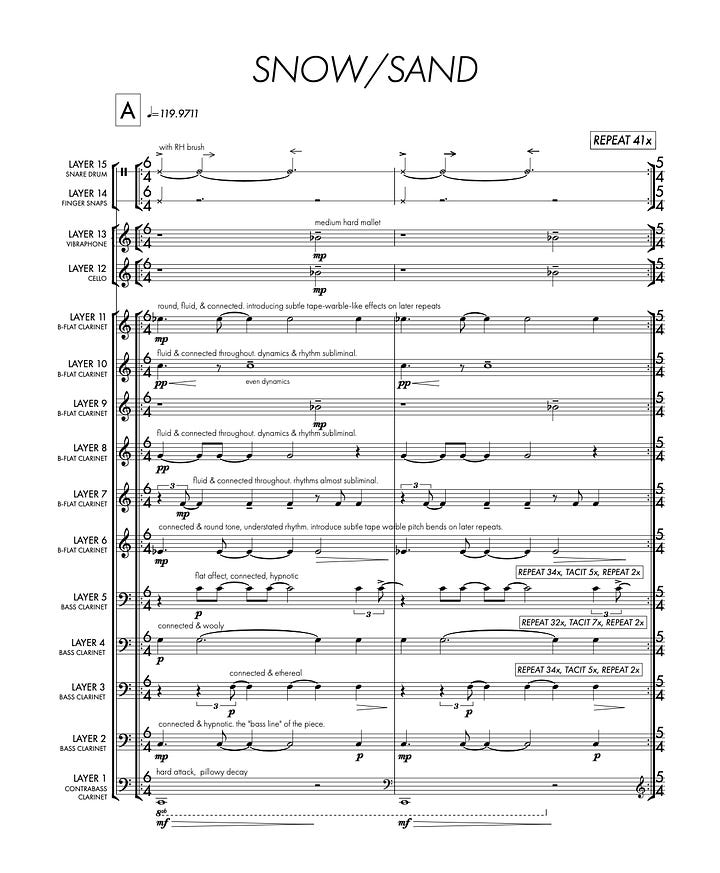

[There are] four pieces on the original album, and the new album has acoustic arrangements of all four. But because I was, in the beginning, a little bit overwhelmed by the prospect of doing the whole thing, I said to Taylor, “well, I don't really know if A) I can do this, B) if it's worth doing, and C) if it's going to sound any good or you're going to be happy with it. So given that, why don't we just start with one piece out of the four, give it a shot, and then if it totally stinks we can just pull the rip cord without too much pain and suffering. If we're happy with it, then we can do the next one.” So it was this sort of like middle ground where I couldn't get my head around it, but I was like, “this seems like something that could be fun, so let's give it a shot.”

So, we went in and did this first piece with a clarinetist, Madison Greenstone. Taylor had mentioned in his initial email to me that he really imagined reworking this record with - well, he didn't specify it in a direct way, but he said he had some ideas for instruments, and some ideas he mentioned were clarinet and cello. When we approached the first piece, we talked about, “well, we could try arranging it for clarinet.” I had never really worked with a clarinetist or written for clarinet, so that was a bit daunting, but there was this sort of long gestation period where I worked with this clarinetist going back and forth and exploring techniques. I was transcribing from the original Stil. record by ear, and writing down pitches and phrase lengths and a sort of rough notation to just get us in the ballpark at first, just to see what this would sound like.

I remember Madison and I were at my studio during one of these workshop kind of sessions. Right before she was about to head to her train and we were winding down, I said, “can we just quickly record the 14 or 15 layers of clarinet that I had written out?” We quickly recorded them, I edited them real quick as she was running out the door, and then we hit spacebar on the Pro Tools session and just heard it back. I think at that moment, when I actually heard it come back, it turned from this kind of historical or academic project to something that I was like, “wow, this could be really exciting.”

Taylor: Yeah, that was amazing. When Joe sent me that quick Pro Tools bounce - unmixed, just a dozen layers of clarinet - I was like, “holy shit, that's the record.” And like Joe said, I think that's the moment that we realized, “I think we can do this.”

Joe: Yeah. It was sort of an open question until that point.

Taylor: Minus the track we saved for the end.

Joe: Yeah. Well, there were a number of question marks throughout this, and so I kind of tried, with the selection of the first track, to pick one that was in the middle of the field as far as difficulty. So it wasn't exactly the easiest one, but it wasn't the hardest. I figured, “if we can hurdle this first one and it's not terrible, and we're not suicidal, then we probably have something here.” And I think after that first playback, there was that palpable excitement among all the parties to just be like, “okay, this is actually not just an abstraction, but it's actually something that's going to sound pretty cool.”

Taylor: I tried, like a year before I ever contacted Joe, to do this myself.

Andrew: I was going to ask about that.

Taylor: Yeah. I said, “I kind of want to do an acoustic version of this.” So I set myself up with a pianet - I didn't have the Wurlitzer at that time. A pianet and a xylophone, and some mallets and a bow. And within an hour, I knew that I was in way over my head, that I didn't have the chops to play it back. I didn't know how I was gonna do it, so I shelved it and I said, “I can't do it. Some other time, it'll resurface.”

Andrew: And when was that, Taylor? I'm interested to know when you made that attempt.

Taylor: It must have been probably two years before I ever contacted Joe. Maybe a year or two, not too long ago. But you know, it must've not gotten so far out of my memory that I said, “I'll never do it.” I eventually realized I could do it. Maybe it was longer before that, because I realized Joe was doing a similar thing with our friend, Kenneth Kirschner's music. So, yeah, I guess it could have been a couple or a few years before Joe and I did this, and then I saw what he was doing with Ken. I was like, “ah, maybe Joe can do this,” and so I contacted him about it.

Andrew: Yeah, and you guys are reading the script perfectly. That's where I'm gonna go next here, is the actual process. And before I get into that…Joe, the work that you've done with Kenneth in the past, I'm sure had a lot of parallels to this project and I'm sure you tapped into that experience, but I'd love to hear your take on how you approached the process of transcription. I'm just thinking of this as such a monumental effort, because I have a background in orchestral music; I grew up playing trombone, and I was actually pretty decent at it and played in bands growing up. I have some basic sight-reading and compositional ability, but I can't even get to grips with how you would notate and articulate some of these details that are in the original album.

I've got a lot of questions here, but generally speaking, how did you approach this process of transcription? How were you isolating layers and sound sources, and what led you to choose certain instruments over the others? I heard you mentioned that Taylor had an idea of some instruments that might fit texturally, but what else was going into that process as you went through it? A huge question, I know, but take us through what that work was like to get through.

Joe: Yeah. Going back to the first piece, which again…because the whole task seemed a little overwhelming at first, I just - and this is typically how my mind works - I just tried to think of, “well, how can I break this down into something that's manageable? How can I solve one problem here?” There were a number of problems, like the first problem which I didn't really know at the time, because Taylor emailed me and I just assumed there would be a multitrack for this record and I could just solo “granular pad one,” and “beep sound two,” and I could solo all this stuff up, but that turned out to not be the case.

Taylor: Nothing. [laughs]

Joe: So the first hurdle was, “okay, I have to start basically from the record as released.” There was nothing - there was no backing tracks, right? There's no soloing “beep sound one.” So this question [came up]; it's an interesting question: “what is a unit of sound? What are we calling a unit? What is one sound?” It sounds abstract, but it becomes very practically relevant when you're trying to transcribe, because you could be like, “well, am I going to represent the sound with one instrument, or multiple instruments? What is a unit?” In the electronic world, and with the processes that Taylor was using, it's very unclear at times.

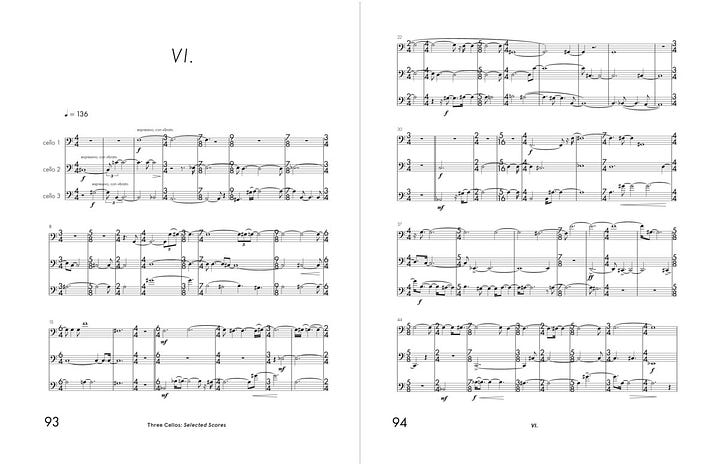

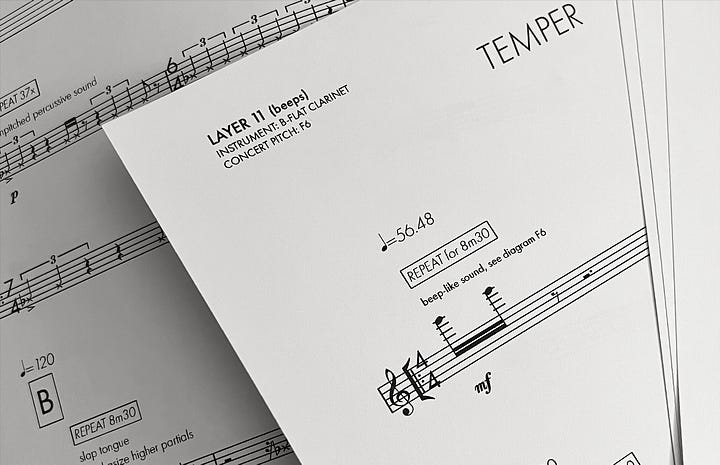

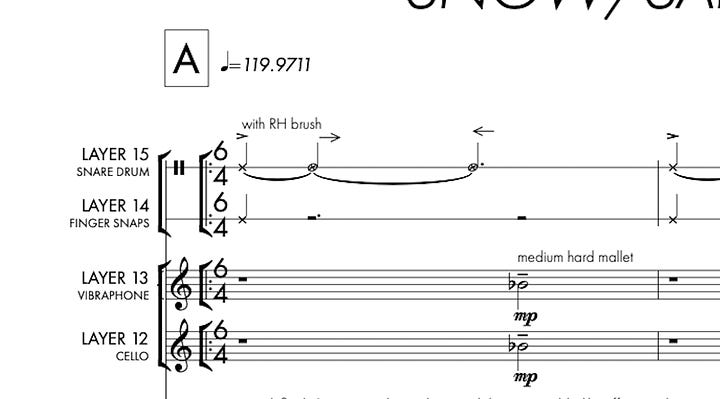

So, the first thing I did - if I recall how I did it - the first thing I did was on this track called Temper, the one that we did for…I think it was 15 clarinets and a shaker. I took the stereo file, I put it in Pro Tools, and I put some markers in, just generally: “okay, this is a D flat major section. This is D flat Dorian.” Just putting in markers. “Here's a fade out…” And then from there, I took a digital EQ and I started just [applying] low pass filter, high pass filter, just playing around with the spectrum. “If I cut out all the highs, what am I hearing?” I would just scoop out all the highs. “All right, now we've got this tonal bed. What's going on in there?” So I would just start listening and hearing different notes. “All right, we've got, D flat, G flat, D flat, G flat, F, whatever notes I'm hearing…A flat, B flat, C, there's a bunch of notes. I can pick them all out.” I find the registers, write them down on manuscript paper.

Taylor: If I can jump in: seeing Joe do this, it was an amazing way of thinking about it. He used, like he said, a digital EQ plugin with extreme filter slopes on either side. So he's basically creating a very extreme bandpass filter and sliding that around.e

So you have this whole dense song, but if you're isolating 400 Hz to 450 Hz, you're around an A, and you can see where these dense songs are built up. [They] may have been chords or pads or something, but there's individual notes in there somewhere.

Joe: Yeah. Exactly.

Taylor: Joe would zoom in on those with very narrow EQs, and completely eliminated everything above and everything below that EQ point.

Joe: And you can just do it. You can just take the Stil. record and just try it. Just put a low pass filter and move it around, and when you get to a certain point, you'll hear all the top end percussive stuff cuts out, and now you have it.

I'm talking about the first track temper that I worked on. And like Taylor said, now you can isolate these “spectral nodes.” And yeah, having a background in traditional composition and the kind of stuff you were talking about, playing instruments and ear training and stuff like that, I could pretty quickly figure out the notes. But from there, what was more challenging was to figure out what the phrase structure was. Now you have this 400 hz bandpass thing, but it was like a strange murmuring, kind of like… [imitates bandpassed murmuring sound]…just these murmuring tones. So now, I have to say, “okay, not only do I have to know vaguely what this is, we have to put it on a grid so that we can build a click track so that we can build a score, so this all relates. It was pretty painstaking at first, but I would just try different clicks…or then I would start to, by ear, be like, “okay, every 14 and a half seconds it repeats, so if I just take out a calculator and calculate the BPM, it's got to be something around here. It's this many quarter notes…” Just vague math. “All right, it's four measures of 3/4 at blah, blah, blah BPM, and that sounds about right, but now it's getting a little ahead after a minute. So, slow it down by half a BPM.” And eventually you wind up with these things like [where] it's 4/4 at 56.137; stuff literally like that: ”okay, that's the BPM.”

I don't know how Taylor made this stuff, honestly, and he could speak to it, but it wasn't made in a DAW. It was made with these nonlinear, granular buffering things.

Taylor: I don’t know how it was made.

Andrew: Yeah, that's where I was going to jump in and comment, because I pulled up the original liner notes [for Stil.] and was going to [read it] for people listening here, and for context. It says here - I'm just reading from the album - that,

“The sound of Stil. is built using melodic and granular passages juxtaposed in variable length loops, creating layered and embedded rhythms and highly variable structures of repetition.”

So, I mean, you know that you're going to encounter a serious challenge with figuring out, like you said, correct phrase interpretations, and timing, and BPM and all that. Just to set the stage here for people, this is a huge challenge.

Joe: Yeah. One more layer I would add to that, about this overlapping loop length thing. This relates back to the Kenneth Kirschner music that we were talking about before, and some stuff that I was able to bring from that is that I noticed that Taylor and Ken - I mean, their music is, on its surface, very different. But there's actually a technique that both of them use, which is asynchronous looping, which is basically the idea of multiple sounds that are layered over one another, or phrases that are layered over one another, but they don't share a common grid. They don't share a common clock. They're running out of sync.

In Kenneth's music, it has a very different effect. It's a harmonic effect. He's really interested in these vertical harmonic structures and effects…but in Taylor's music, it's often very rhythmic, polyrhythmic, or just textural: playing with different kinds of densities, and different kinds of speeds and clocks and stuff like this. So, the other challenge was what I just mentioned: if I've isolated all these tonal elements in the track, and those are running at 56.14 BPM, now there's another element - a beeping sound or a clicking noise - that I would transcribe and find running in a mixed meter situation. It might be 5/4 or 7/8, plus 5/16, plus 11/16 at 71 BPM…now we have not only a complex structure for one layer, but there's now multiple layers that are overlapping with different BPM. I just kept at it until I figured out what it was. When you say it out loud, it does sound kind of crazy, but in a sense, once you've done it on one piece…it's time consuming, but it's just figuring out what's going on and eventually you get it. Eventually you're like, “that's it. I figured it out. It's 71.43 BPM. That's what it is.”

Taylor: And that's exactly what I intended.

Andrew: Right. I'm sure it’s exactly as you drew it up.

Taylor: The whole thing was a big test for Joe, just to see if he could unlock it.

Joe: This would be a really terrible ear training exam at conservatory. I hope I got a B minus, at least.

Andrew: So then, there's that challenge of the literal transcription, and then there comes a certain point, I guess, where you had to make some kind of subjective judgment call - or maybe it wasn't subjective. I don't know. But I'd love to hear how you went about the process of choosing which instruments [you used], or which performers you reached out to. How did you decide what and who was going to play these parts once you had a general sense of what the actual score was looking like?

Joe: Well, it wasn't, it wasn't in that order. Taylor had a lot of ideas on that front, and I tried to just do justice to his ideas, in a lot of cases.

Taylor: I mean, I think the only thing I really remember is telling you that I really liked clarinets and oboes. I told Joe in the beginning that I want to make these as close as we can to the originals, but I'm not going to be super precious about it. And if something needs…I mean, I think some of the tracks definitely vary. The composition, the arrangements, they vary a little bit from the originals. So I suggested a few instruments, but ultimately told Joe that whatever serves the piece the best is what we'll do, and I'm not going to be precious. We don't have to get every millisecond exactly the same. The lengths of the tracks are different, arrangements and endings and breakdowns are a little bit different. Whatever served the piece in the end. I mean, they're pretty damn close to the originals, but they're not exact. The character and the vibe is there.

But to your original question, the instrumentation I'll leave to Joe to talk about, because he was the one transcribing these and he has the knowledge of, “well, this range, this rhythm, this range of sound will be good for this instrument, and these kinds of sounds will be good for that instrument.” He can expand on that.

Joe: Well, I will say, I credit Taylor. A lot of the instrumentation discussions, we did have together. I mean, there were some cases…

Taylor: Yeah, we’d listen and say, “we could do this and that.”

Joe: …yeah, we would kind of riff at [his] studio and listen to the tracks. The first one, like I said, for that I was kind of on my own. I was like, “Taylor asked me to do this. I want to present him with something.” And then I gave that back and you were like, “wow, this sounds amazing, let's move forward.” At that point, it did become a little more collaborative.

We would sit, we'd listen. Taylor would say, “well, what if we did this?” And I'd say, “well, that might not work [with this register],” or “that actually would be cool, and I know this person who's really good at that kind of thing and they would be perfect for this.”

So, some of it was just people that I knew who played instruments Taylor was mentioning he wanted to work with, and sounds like that. And then in other cases, the sound palette was really just dictated by what was in the electronic version. There's certain sounds there, and there's just not a lot of leeway. They could only be done by certain registers, and only certain instruments will be able to cover those registers. In some cases, we had to get creative with how to orchestrate things, and so it was a bit of a mix of a top down thing of like, "we want to use these instruments,” and then it was a bit of a bottom up thing of like, “well, it can only be done by X, Y, or Z and I only know these people, and they're available on these dates.” It was all those factors.

Taylor: [It took] pretty amazing players, too, to pull it off, especially the clarinetist to pull off some incredible techniques. You listen to Temper, and it's all clarinet. There’s beeps and scratches and static and all of these sounds that all come from the clarinet, and it takes a pretty good player to pull that off. Madison wowed us.

Andrew: Yeah, the extended techniques and even the durational aspects of this had to have been extraordinarily challenging to perform. It is incredibly impressive to know that there's a human being behind these sounds…when you hear it in context, [it’s] pretty amazing stuff.

And maybe that's a good chance to ask a question, too: you kind of hinted at it a little bit there, [when you said] you weren't being too precious about it, but was there a certain amount of leeway that you gave the performers to add embellishments in the moment? And how much of that ultimately made the cut into the final album?

Taylor: I think Joe can probably speak better to this, since he'd sort of produced the whole thing. From my observations, [there was] not a lot of leeway, in that Joe had it really specifically notated and arranged. And there'd be times when, “Oh, we need some tape warble. How do you [do that?],” So we asked Madison, “how do you give us tape warble?” She would come up with that effect, but it would be pretty much on Joe's direction and in specific spots.

Joe: With that example, the tape, I remember we started notating that with quarter tones and eighth tones - [we were] that specific, as far as where the pitches are warbling and what's happening.

Taylor: I don't think there's a lot of improvisation.

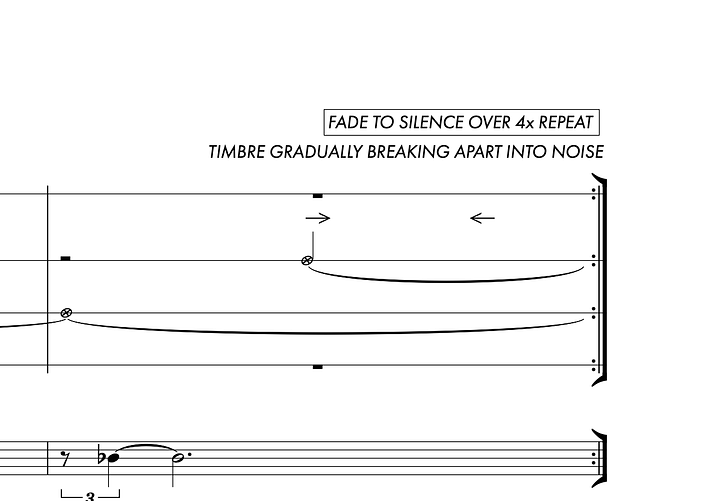

Joe: Well, there was one exception to this, which I think is interesting. When Taylor first contacted me, one of the things he said, I remember, was, “I want all of it to be not only acoustic, but I want it to be played. I don't want to record a bar that's looped in Pro Tools.” And there was one question around this that I was thinking about, because the tracks on the record, the original record, they all have these fade outs, or at least most of them have these fade outs. They're these digital fade outs…

Taylor: You’re going to talk about the fades on the new one? Yeah, that's the best part of the record, right? Pay attention to the fade outs of all the songs.

Joe: So these are the exception, where we said “well, if he wants it to all be played, then we shouldn't just record the ends and then do a digital fade. We should try to actually have the players try to do the fade.”

That was a moment where we were able to give some leeway and say, “let's lean into this a little bit. It's going to be a bit different from the original, and if the sound starts cracking or if there's these sort of imperfections or moments where things are…” because when you get to a certain point, you try to play at a certain low dynamic that's approaching silence, it kind of starts to crap out on you a little bit.

Taylor: Your clarinet is more breath than it is tone.

Joe: Yeah. And those moments - we tried to amplify that more than shy away.

Taylor: The fade outs are Madison playing quieter, but also, like Joe said, it starts to break up and you try to play quiet, but there's only so quiet you can play on a clarinet before it just turns into breath and clicky noises. But that was the fade out, and all the instruments did that. The cello did that, and the fades were naturally performed.

Joe: Yeah, so that was an instance where I would say there was definitely some leeway.

Taylor: …and they were pretty long, too. It might be a 30 second or longer fade, and we tell the musician, “okay, you can start to fade here, and just do whatever you can do to get quieter for a full minute.”

Joe: Yeah. I mean, most of it, yes, I think that's probably the right answer. Most of it was pretty well notated, but there was definitely moments around the edges where we would have some happy accidents, especially those fade outs where the performers really brought some of their own subjective selves to the process.

Taylor: Or just riffing on clicks and noises. Joe would say, “we need some clicks. How do you give us clicks?” And the musicians would figure that out and experiment with some things.

Andrew: Yeah, that's awesome. That kind of attention to detail, even in the marginal places like the fade outs and the things that people skip, I think is a really important piece of context. And that takes me to my next question here, is that, Joe, I know this is a part of a new series that you're doing with greyfade called FOLIO.

For the uninitiated here - and I'm sure people will see it when the album is out in the wild and available to be looked at and all of that, but I just really resonate with the idea that you've got going here, in adding as much context and background to the album as possible, in a beautiful way, in an object like a book. I really think that's a crucial piece of experiencing this album the way that you probably intended it to be heard.

Excerpt taken from greyfade’s FOLIO homepage:

Since its founding in 2019, greyfade has taken as its basic premise the idea of the musical album as a complete conceptual universe unto itself, integrating sound, compositional architecture, visual design, and text into a single object worthy of sustained engagement. To bring these threads together in a single physical form, the label’s next phase of development will explore a “new” medium: the book.This cycle of music releases will be presented in an innovative new format: a 6.5 x 8” hardcover book with an included high-resolution music download. Equal parts album release, critical text, making-of narrative, study score, and collectible art object, the FOLIO format brings together what we believe to be the best of the physical and digital worlds.

Developed in collaboration with Penguin Random House art director and book designer Jason Booher, the intricately designed and carefully manufactured linen wrap hardcover editions feature essays, extended artist statements, reflections on process and technology, data visualizations, music theory, photography, and musical scores – offering an unprecedented level of detail and insight into the music’s conception and creation. The included high-resolution music download is sourced directly from the studio masters, providing listeners with a digital listening experience of the highest quality and ownership of the music for years to come.

The FOLIO format represents a renewal of greyfade’s commitment to the continued relevance of both thoughtfully designed physical objects and high-resolution digital music, bringing greater context and depth to the label’s most ambitious musical projects.

So just to take a step back from the actual album, Stil., and look at that series that you're working with here, can you talk us through the inspiration for FOLIO, it’s overall ethos, and what led you to explore this for this project in particular?

Joe: I wouldn't say I'm the first to think of the idea. There's been labels that have explored this kind of territory before, but the inspiration and the impetus comes from thinking through why we want to be releasing physical music as a physical product. I've done a bunch of releases in vinyl format and other formats and kept thinking that I love the physical communication aspect, to have something to hold in your hands and for the listener to take home and have a ritual where they can engage with the music. I just thought, conversations like these that we're having, where you really get a sense of the background and a sense of really what went into things on a little more detailed level, that was something that was missing in the landscape.

For me, personally, I really love going to bed and listening to a classical piece and reading through the score. I really like reading a book of essays about a certain composer and really getting into their mindset, and understanding not only the aesthetic choices they might be making, but really getting into the nitty gritty of some of the technical details of how stuff is made. I guess there would be some that would say, “well, that's all fine, but it's separate from the music. The music stands alone and speaks for itself, and doesn't really need any context.” An earlier version of me might have agreed with that, but I'm starting to come around to the idea that in today's digital landscape, where there's not really a lot of context around “content” - you’re just served this decontextualized content without any backstory to it - I think there is a function right now for giving people a really substantial piece of context on what goes into making a project like this. It's not to toot our own horns or talk things to death, but I think there's an interesting discourse that goes on; a technique that you might be able to learn from. I don't know about you, but I love reading old interviews with musicians, heroes of mine. I like hearing [about], “how did they do this? Why did they do this? What was going through their head? What was the story behind it?”

The FOLIO series is, I guess, my humble attempt to try to put some of that right alongside the album, so you can experience the music and some of that contextual information side by side. And hopefully they reinforce one another, and give you a little more depth and sense of personality and personalization to the experience of listening to the music.

Taylor: I'll just add as well, Joe and I were deep into this project. A year into it, we realized just how much of an insane amount of work it was, and we basically said at the end of the day, this can't just be some streaming release. We did all this work with all this incredible stuff we've talked about for the last hour, and you just release it on Spotify? That was not an option. I don't know how many times Joe and I used the phrase, “we're going all in.”

It's like, “we've gone this far, let's do a double LP.”

“We've gone this far, let's do a book.”

“We've gone this far, let’s print the scores.”

“We've gone this far, let's perform it live.”

It was so much work and such a project, and it took so much out of Joe, that there was no option but to present the whole story.

Andrew: Yeah, I really appreciate that. And I totally agree with you, Joe. I like to read those interviews, too, and when the score is available, I think it adds a huge amount of backstory to the whole experience of hearing an album. I mean, that's what I'm trying to do here with this podcast and my Substack page, where I'm writing about this stuff and offering the context. I just think it's really important to do that. We're talking about this kind of stuff here, but I should mention that you both operate very purposefully designed and principled music labels, so having the context behind the work that is chosen to appear on these labels, I think is really important.

And you mentioned it just now, Taylor, but you mentioned that it took a lot out of Joe to make this, and that this was a huge effort and you realized what a big undertaking it was about a year into it. With this whole process in the rearview now, at this point, I would love to hear each of you talk about how your relationship to the original album has changed. Has the passing of all this time since its release, and then all the time that this project took to take it to completion, do you, find yourselves looking back at that original in a different light? And if so, in what way?

Taylor: For a minute there, I thought you were going to ask what our relationship with each other was. [laughs]

I don't know if I've really…I have difficulty listening to my own music, so I have not gone back to the original except when Joe and I have needed to listen to it to deconstruct it or whatever. When you redo an album - and I've done this with some other albums - you're often looking to improve on it, or to say, “this is what the album was supposed to be.” And that's not the case with this one, because Stil. wasn't supposed to be an acoustic record. It was very much an album of its time, of digital technology. The original, to me, is as important as this one is. This new one isn't a replacement. It's not an “either/or” situation. I think it reflects my own journey as a musician over the years, going from someone who is very interested in digital technology and then incorporating more and more acoustic and analog instruments into my music. It makes sense to me, to go this far, and it's exactly what I wanted it to be, which is a reimagining: “if I was going to do this album today, if the album never existed and I had this concept, and I was going to do it today and I had the means, what would I do?” It would probably be this.

And as the release comes out in May, we're going to make a point for people to listen to the original, because I think this one is more interesting if you hear where it came from. It's really cool when you hear it, but if you listen to the original first and then listen to this, you're amazed at how Joe has pulled this off, and it makes much more sense hearing both of them.

In conclusion, to me, it's not a replacement or something better or something worse. It's a reimagining.

Joe: Yeah, I agree with Taylor. It's not an either/or, and I go back to where we started [this conversation], about me coming into this project and having the hesitation about it. For me, the original album stands as a great album, and an album that I have my own personal relationship with. In a way, this new project seems…it's strange, but it seems almost unrelated. I can't put my finger on it, but it's almost as if Taylor provided this abstract text that we were able to work with, and to breathe life into, and give a new dimension to it.

But ultimately these [new tracks], while they're obviously very, very related, I think they can both work independently, or, as Taylor was saying, you can listen to one and then shuttle back and forth to the other one. I guess the other thing I would say is, in doing the arrangements, I kind of always knew that, at the end of the day, people would do that. They would be…you're always comparing it to something, right? So the new project, it never could be a standalone. It always refers to something else, and so it needs to work on that level, as well as working as just a standalone piece of music. You should be able to listen to it front to back and enjoy it as its own thing.

But ultimately, they're meant to be heard as a kind of continuation of one idea.

Andrew: That's so interesting to hear, because I do feel the same way. It's like, you know that they are related, but they're not…I don't know how to describe that really well, but I think that's sort of an interesting way to look at it. I felt kind of the same way: “I know these things are connected, but they are very different and unique.” Like you said Taylor, I think it is really imperative that you listen to both of them to get the full experience of this.

And I should say, too, you guys are performing this live on May 22nd at Public Records in New York, probably my favorite venue on the East Coast, personally. I just love that room, it always sounds fantastic.

We were talking a little bit about the performance aspects while you were recording the album, but how are you approaching that show? I imagine that is a challenge in its own right, to take that out of the studio and onto a stage. How are you thinking through that performance? Is it going to be live instrumentation accompanying you, or how are you approaching it?

Taylor: I'm just going to hit spacebar on iTunes.

Joe: We’re going to have someone DJ the original record.

[laughs]

Taylor: We talked about it a little bit, because there's a number of ways you can do it. I mean, this is one thing [for which] we did not say, “we're going all in.” To get all the performers up there…I mean, Madison's the only clarinetist, and there's 15 or 20 clarinet loops, right? So with the players, we talked about, “do they follow a score?” Ultimately, we've decided to generally improvise, and generally play the last track called Stil….

Joe: …with the instrumentation from the record, but you know, in a looser sense.

Taylor: That song on the on the recording is almost entirely Joe playing vibraphone. Isn't there a bass drum in that one? So the live performance will be Joe on vibraphone. And because we have a limited amount of time - even getting rehearsal time was not easy with the musicians - our general goal here is to deliver a performance which encapsulates the whole album in 30 minutes, sort of like an improvised…if you hear the performance for 30 minutes, you're going to kind of get an overview of the album. I think that's the goal.

Joe: I think we both realized - and hindsight’s 20/20 - this is a studio project in a certain sense. And, I mentioned all the multiple tempi and everything that goes into some of the pieces on the album…to try to pull that off in an accurate way live, I mean, I guess theoretically it could be possible, but…

Taylor: I think we need 30 musicians or something.

Joe: Yeah, and I don't even know if it's interesting, because at that point, it just becomes [us] just trying to recreate the thing that's already been realized perfectly on the record. So I think we're approaching performances more as another instantiation of this, to now take these musicians and these relationships and this sort of language that's been developed from the record, and try to bring that into a performance setting that's not quite as notated. I mean, it'll be notated, but yeah.

Taylor: We'll use Madison. We'll use the clarinetist and the cellist, and is Ben [Monder, guitarist] playing? And the guitar to sort of riff around the track, the last track Stil. And they're on that track. I mean, that track is vibraphone and bass drum, so that's where the composite of the whole album comes together.

Joe will probably stick to the general notation of the song Stil., but add in clarinet and cello and guitar, to sort of enrich the whole thing and make something new. And then I'll probably do some percussion, and maybe…we haven't totally figured this out.

Joe: This is good. We're getting our rehearsals on. Thank you for this.

Taylor: I don’t know. I may use some loopers. We may bring in some technology, like loopers and things, where I can capture parts of the musicians. But, I think that's the general [idea]: just sort of riff on an idea with all the musicians for a half hour.

Joe: I think we've had our fill of the “OCD, everything perfect, everything accurate” thing. And Taylor was like, “let's just get together and have some fun.” So I think that's the goal.

Taylor: Yeah, the idea is if you hear the performance, you're going to get the vibe of the whole record.

Joe: Yes. Right.

Taylor: Now, it’d be a dream of mine one day to have the whole record performed, start to finish, by a giant ensemble of instruments, down to the 1,000th of a BPM I suppose…the scores are there.

Joe: See, this is how all these things start. [laughs]

Andrew: We're opening up the floodgates here. Well, I have one more question if you're up for it. It's sort of a big, meta one, but after this has transpired, and you've been through this process: what was the biggest learning experience or takeaway for each of you? After having gone through it, is there anything you're going to remember especially about it, more than anything else? What will stick out in your mind when you look back on this project?

Taylor: For me, thinking back to when I tried to do this myself for an hour, and realized that it was probably over my head…I didn't realize how much over my head it was to do it right. And just looking at the amount of work that Joe did that I'd be completely unable to do really stuck with me, and how he’s still talking to me and still wants to hang out. Because it was a lot of work, and beyond my wildest imaginations it somehow got created. My humble beginnings of banging on a xylophone, and stuff like that, maybe that would have been cool in some way, but I never imagined it being so detailed and so amazingly realized and produced.

Andrew: How about you, Joe?

Joe: That's a really hard question. I still feel so close to the process. It's hard to really have an overview, or even to look at it in the rearview, but I guess I would say, sometimes there's a seed of an idea that provides rewards and you don't really know what they're going to be, and it's important to at least take the first step to try to see what could become of it. The things we said about the hesitation that I felt about this, a lot of it was possibly warranted, but I think ultimately taking that first step into it and trying it, and just making a sketch of something, I guess as an artist, that's really all you can do with these types of hurdles and challenges: just take a first step and put something down.

And if it turned out that that first track we made was absolutely terrible, then we would have moved on and then it would have been fine, too, but it turned out that we liked it. [It was] interesting and led to some other stuff. So I guess my point is that, in a way, it's helped free me from this idea that there is this idea of canonical albums that get made in this perfect space. Everything is in process and progress, and you enter into it and you do the best you can, and hopefully it's meaningful for people. That's about the best you can do.

That's kind of where I end up on this. I don't really know what we've made, what we've done, but I feel like it was a big learning process for me and super worthwhile to do.

Taylor: And we're all in this for a challenge, right? I know it's challenged Joe. I hope he's learned something from it and taken something from this project that will make his next project more interesting, and maybe easier. Maybe the musicians involved found some new techniques to their playing that they never thought they'd do before, and that they can use on a future project.

Joe: Yeah, it continues. It doesn't just stop at an arbitrary point. I think that, for me, is a big insight. It continues on.

Andrew: Well said.

Taylor: And I do honestly wonder if I'll ever ask Joe to do an…I'm not saying that as a joke, not as a joke! [laughs]

I mean, we have to admit that it worked, right? It worked. So is there something else that we can do?

Joe: Andrew, I'm blaming you if this happens. I’ll get asked to do Occur in a week. You're going to have an email from me, a nasty email, if this is what happens.

Taylor: But seriously, certainly not in the immediate future, but who knows?

Joe: I mean, it’s been amazing to work with Taylor. Taylor is one of my absolute musical heroes, and so this has been just an absolute honor. I hope that we can find some other way to move this forward, because it's been a pleasure to actually be able to collaborate, finally.

Andrew: Yeah. Well, you've got two huge fanboys here, Taylor, because you're definitely up there for me, as well. It's been a pleasure to get this insight.

And you beat me to the punchline, Joe. I was going to say, I'll see you back here in five years when we're talking about the reimagined Occur. Book it now, we'll get it on the calendar.

Well, thanks guys. That was awesome. I really appreciate all the insights here. And of course, I'm going to link heavily and thoroughly to all the materials and places to buy this in the show notes, and then on Substack too. I really look forward to seeing it out in the world, live, and look forward to hearing what people make of it. I think they're really going to love it.

Thanks again for taking the time.

Taylor: Thank you.

Joe: Thanks. Thanks so much.

Sound Methods 007: Taylor Deupree & Joseph Branciforte